Continued from Part 1

To amuse myself before the football games came on, I decided to walk from my home in Little Neck all the way to 71st/Continental Avenue in Forest Hills. It was a rare 67-degree day in January. The route I chose was one of only two available to walkers, because there is a barrier of parks and expressways separating Douglaston and Little Neck from the rest of Queens. I could have used Northern Boulevard, which runs through Udalls Cove, over Alley Pond Park and over the Cross Island Parkway, but I had done that countless times on foot, in a bus and on my bicycle. Instead I swung south, along West Alley Road, the only survivor of a group of “alley” roads in eastern Queens. The “alley” in question runs through a valley carved out by a trickling waterway running south of Little Neck Bay. Few roads traverse it.

I then traveled generally along 73rd Avenue and Jewel Avenue west through Flushing Meadows to Forest Hills. The low January sun was in my eyes much of the time, but the temperature was pleasant. I mostly walked through Oakland Gardens and Fresh Meadows. Before mid-20th Century, these realms were dominated by golf courses, country clubs, and farms before that. Today, they feature clusters of garden apartments — but the development of the last century couldn’t erase all of these areas’ history, and I’ll concentrate on some of it here.

GOOGLE MAP: LITTLE NECK TO FOREST HILLS

Traveling west along 73rd Avenue, Meadowlark Gardens is yet another in a lengthy string of garden apartment complexes at 197th Street. Some co-op owners have the benefit of enclosed porches outside their apartments.

The Klein Farm, 73rd Avenue and 195th Street, sold produce for years in a roadside stand until 2003, when the family sold it to a realtor. The farm had been in operation here since 1895. Since the farmhouse (which is still standing) and property have never been landmarked, they are now under the gun from developers.

The Kleins once owned approximately 200 acres in the area; some of it was sold in the 1940s to NY Life Insurance, which in turn built Fresh Meadows Houses. The late Parks Commissioner Henry Stern recognized the Kleins’ farm legacy by naming the adjacent playground for it in 1999.

There is one remaining large working farm in Queens: the Queens Farm Museum, located on Little Neck Parkway north of Union Turnpike. In the fall, I’ve attended their “tavern nights” when a meal in the style of the American Revolutionary-era is served by candlelight. In the summer, events include Native American powwows.

73rd Avenue is the southern boundary of the biggest garden-apartment complex of all in eastern Queens, which is of course Fresh Meadows. I’ll discuss it only briefly here, since I talked about it previously in greater detail on this FNY page. Fresh Meadows has its own street layout and even its own proprietary street lighting.

The extensive residential community centered at 188th Street and the Long Island Expressway was constructed between 1946 and 1949 by the New York Life Insurance company. Prior to the apartment complex, the area’s claim to fame was Fresh Meadows County Club and golf course that hosted the U.S. Open in 1932. The housing mix is 3-story apartment buildings in garden settings, with a couple of high-rise towers.

Fresh Meadows History has some vintage photos from the 1940s and 50s.

Fresh Meadows takes its name from its contrast to neighboring Flushing, whose name is a transliteration of the Dutch “Vlissingen” meaning “salt meadow valley.” Ponds and creeks running through the neighboring area to the southeast were likely “fresher” or free of salt, and so Fresh Meadows replaced the harsher-sounding older name for the region, Black Stump, which apparently referred to burned, blackened stumps that marked the edges of farms.

At first glance 182nd Street north of 73rd Avenue looks like any other in Fresh Meadows. It’s lined on both sides with attached and detached houses. However, there’s an unmarked empty lot on its east side with weeds and ivy among its trees.

This is the cemetery of one of the farming families in the area, the Brinckerhoffs; there are 76 plots here dating from between 1736 and 1872. The tombstones have been long ago stolen or are buried underground.

In the summer of 2012, the Brinckerhoff Cemetery was designated a landmark, ending a multi-decade tug of war between preservationists and developers hoping to build atop the cemetery.

The Brinckerhoff family arrived in New Netherland in the 1630s and had acquired land in what would be Fresh Meadows by 1730, and the family cemetery was instituted near the farm shortly after.

The cemetery was in active use until the late 1800s. Though surrounding properties changed hands often in the early 20th Century the cemetery and neighboring Brinckerhoff homestead were always excepted.

The cemetery was subject to frequent vandalism and the homestead was demolished in 1934. The cemetery property was transferred to the city to the DeDomenico family in the 1960s, which sold it to Linda’s CAI Trading in 2010. I have more information, including some pictures of the cemetery’s old tombstones, on this FNY page.

The Brinckerhoff, or Brinkerhoff, family owned a lot of territory in Queens in the 19th Century. 110th Avenue in South Jamaica and St. Albans is co-labeled on its street signs with Brinkerhoff Avenue.

I decided to take Jewel Avenue into the heart of Forest Hills for the rest of today’s walk, but if I were driving, I couldn’t do it from 73rd Avenue any more, as the Department of Transportation has decided to make Jewel Avenue a dead end before it can intersect with 73rd!

Jewel Avenue is an unusually named street in that it has kept is name while parallel avenues have numbers. It’s part of a former group of streets in alphabetical order in Forest Hills.

Jewel Avenue kept its name, perhaps, because it’s the only one of these streets that continues across Flushing Meadows-Corona Park all the way to Fresh Meadows. It’s the only remnant of a group of streets east of Queens Boulevard in Forest Hills named in alphabetical order that turn up on maps from the early 20th Century. The streets in sequence were named Atom, Balfour, Chittenden, DeKoven, Euclid, Fife, Gown, Harvest, Ibis, Jewel, Kelvin, Livingston, Meteor, Nome, Occident, Pilgrim, Quality, Ruskin, Sample, Thurman, Uriu, Verona, Webb, and Zuni; it’s likely the streets were only on the planning boards till they were built mid-century, by which time they carried the numbers (68th Road, 68th Drive etc) they do today. Jewel Avenue one of the few non-numbered streets, along with Northern Blvd. and Roosevelt Avenue, that cross Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

Jewel Avenue, east of Flushing Meadows, shares its street signs with Harry Van Arsdale, Jr., making for some relatively unreadable signs. I’ll discuss who Van Arsdale was a bit later.

Utopia Parkway is a major north-south Queens route, running from the East River in Whitestone south to Grand Central Parkway in Jamaica Estates, where it becomes Homelawn Street. It’s named for a real estate development that never panned out, and overlays part of an older route, Fresh Meadow Lane.

In the early 20th Century the Utopia Land Company, named for the term for a perfect or eminently desirable place coined by author/scholar Thomas More in 1516, planned to build a community of co-operative apartments for Jewish residents of the Lower East Side. The company spent $9,000 to build and grade streets and divide area lots. However, it was unable to acquire further funding and the plan was abandoned, with the newly built Utopia Parkway its only legacy.

Alongside the regulation mailbox at Jewel and 172nd Street is a pebbled concrete pole that used to support a much smaller slotted mailbox, the type seen on this FNY page.

Young Israel of Hillcrest, Jewel Avenue at 170th Street.

Young Israel was founded in 1912, in its earliest form, by a group of 15 young Jews on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Their goal was to make Orthodox Judaism more relevant to young Americanized Jews at a time when a significant Jewish education was rare, and most Orthodox institutions were Yiddish-speaking and oriented to an older, European Jewish demographic. [wikipedia]

The name Hillcrest refers to a small residential area of Queens wedged between 73rd Avenue and Union Turnpike between Fresh Meadows and Jamaica Estates. It can be found south of the generally hilly area, the result of a glacier’s passage millennia ago, through the heart of the borough north of Hillside Avenue.

Housing sampler along Jewel Avenue between 164th and 170th Streets. That A-frame is one of the more extreme I’ve seen.

164th Street is a 4-lane wide route from Flushing Cemetery south to the Grand Central Parkway.

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, a trolley line connected Flushing and Jamaica, running originally through the farms and fields of Fresh Meadows. Service ended in 1937. In short order, the tracks were pulled up, the weeds paved over, a center median added, and 164th Street became the fast and furious stretch we know it as today between Flushing Cemetery and the Grand Central Parkway.

You can see what 164th Street looked like when it featured trolleys, as well as other Queens scenes from the early 20th Century, on this FNY page.

164th Street is the east end of Electchester, a massive mid-Queens housing project originally built for electrical union workers in the 1940s.

The middle-income project was spearheaded by Harry Van Arsdale, Jr. president of Local 3 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. Another part was managed by the City Housing Authority who built the Pomonok Houses, among other developments. Electchester was the latest in a series of housing projects built for specific categories of unionized workers, joining the Amalgamated Houses, Bronx, and Seward Park Houses, Manhattan (garment workers); Concourse Village, Bronx (meat cutters); Big Six towers, Woodside (printers and lithographers).

Electchester was constructed in stages from the late 1940s to late 1960s, and the buildings in the project were named prosaically beginning with the First Houses and going up to the Fifth Houses, which are the two towers on 160th and 162nd Streets. Electchester has an unusual street layout with 160th, 161st and 162nd forming a rounded Y-shaped pattern between 65th Avenue and Jewel Avenue/Harry Van Arsdale, Jr. Avenue.

The project sits on the former grounds of the Pomonok Country Club.

Electchester’s First Houses between Parsons Boulevard and 164th Street resemble the garden complexes found along Jewel and 73rd Avenues.

The Pomonok Houses are a large NYCHA housing project built in 1952, found north and south of Jewel Avenue between 65th and 71st Avenues. I liked its remaining black and gold enamel directional signs.

“Paumanok” was a word used by the Algonquin tribe to describe Long Island. The exact meaning is unclear, although William Wallace Tooker, a 19th-century expert on the subject, thought that it meant “land of tribute.” Other translations have included “fish-shaped” and “land where there is traveling by water.” The name is associated with the Queens neighborhood just east of Queens College.

West of Parsons Boulevard Jewel Avenue enters Kew Gardens Hills…

… With kosher pizza, bagel and a kosher wine shop you can tell it’s a heavily Jewish neighborhood.

Before plunging through Flushing Meadows, Jewel Avenue passes through three more garden apartment complexes, Joyce Gardens, Hyde Park Gardens and Regent’s Park Gardens, the latter two named for large parks in London, England.

“Supertall” towers arrayed along West 57th Street in Midtown are visible from Flushing Meadows-Corona Park as Jewel Avenue passes through. Two roads combine here, 69th Road and Jewel Avenue, complete with on and off ramps for the Grand Central Parkway. Jewel Avenue passes over the Van Wyck Expressway, but is unconnected to it.

West of the park, Harry Van Arsdale Jr. Avenue changes its allegiance, from Jewel Avenue to 69th Road.

Using the camera zoom feature, the Unisphere, symbol of the 1964-65 World’s Fair, and the Arthur Ashe Tennis Center (1997), the home of the annual U.S. Open tennis tournament in the late summer, come into view.

Looking south from Jewel Avenue toward Willow Lake, one of two man-made bodies of water created by Robert Moses from damming the Flushing River for the original 1939-1940 World’s Fair and the simultaneous founding of Flushing Meadows Corona Park. While Meadow Lake, the other new lake, was used for boating and spectacles like the Billy Rose Aquacade (its amphitheater was finally pickaxed into oblivion in 1995) Willow Lake by contrast has always been maintained as a natural freshwater habitat.

After entering Forest Hills from the east Jewel Avenue enters a weird world of overwrought architecture, overwhelming the colonial and federal style brick buildings that had preceded them. There is also some creative conifer trimming.

In fact this stretch of Forest Hills seems to be something of a mad scientist lab where modern architectural designs are trotted out. There’s the spare, boxy look, as well as this Tuscan columned chrome monstrosity. I don’t usually get ideological here in your Forgotten New York, but I have no idea why anyone would be attracted to either design.

And, before I’m accused of disliking modern architecture (post 1950, let’s say) I’ll mention that I treasure things like the Jamaica Savings Bank on Queens Boulevard; Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum; and Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal in Kennedy Airport. They have a sense of place and context that none of these Forest Hills objects can match.

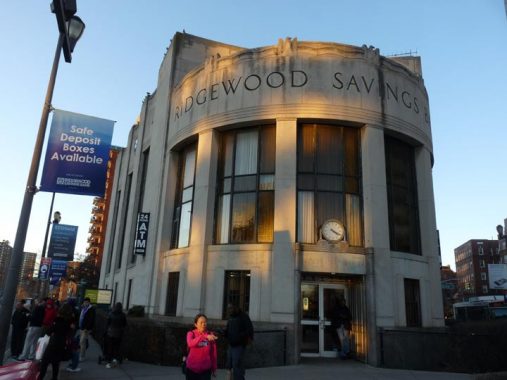

Wrapping up today’s 9-mile walk at Ridgewood Savings Bank at 108th Street and Queens Boulevard, in front of the 71st/Continental subway serving E, F, M and R trains. In Historic Preservation in Queens by Jeff Kroessler and Nina Rappoport (Kroessler is a former board member of Forgotten NY’s associated group, the Greater Astoria Historical Society), this building is described as “without a doubt one of the most handsome commercial structures in the entire borough.” It was designed by the firm Halsey, McCormick and Helmer, Inc. and dedicated in 1939. That firm also designed One Hanson, the Williamsburg Bank Tower in Brooklyn.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

2/23/20

8 comments

Great post (of course) Kevin. Your walk weirdly reminded me of what I think were called the “Hike for Help” charity (Muscular Dystrophy?) walks which I participated in a couple of times as an elementary school student in the ’70’s. Unless I am totally hallucinating, these were 20-mile (is that possible?) walks, that started near Queens Center mall and wound out to far eastern Queens and back in a loop. You would have check-points along the way. I remember a lot of the same neighborhoods you covered here.

I remember it took a loooong time to complete, especially since I think my friends and I stopped at 75% of the candy stores we encountered along the way. Curious if anyone else out there remembers these.

@Jerry Friedman, I also participated in a 20-mile charity walk when I was in high school, but it was in Manhattan, not Queens, and I think it was for March of Dimes (?). In any case, wearing the wrong socks, I wound up with a blood blister on my foot and had to be half-carried across the finish line…to add insult to injury, when I got on the subway back to my home in Brooklyn, I couldn’t get a seat! Ah, good times.

9 miles is an excellent walk and undoubtedly, because Queens is so “dense” with neighborhoods, buildings, interesting stuff, you had to list only the “tip of the iceberg” of what you saw. FWIW, Utopia Playground, at the

intersection of 73rd Ave, Utopia Parkway and Jewel Avenue, is, if memory serves correctly, the headwaters of Kissena Creek! I learned that from Sergey’s great article on Kissena Creek. :~)

Dave in DE.

In the summer of 1965, the garden apartments in the area between Kissena Boulevard and Main Street were in the news frequently because of the infamous Alice Crimmins murder case. In July of that year, Ms. Crimmins’s two children, 4 and 5 years old, were found murdered near the Crimmins apartment at 150-22 72nd Drive. Ms. Crimmins was accused of killing both youngsters, and after years of numerous criminal trials and appeals, she was convicted of killing her daughter and was imprisoned from 1973 until 1977, when she was paroled. An entire book was written about the case in 1975 (The Alice Crimmins Case, by Kenneth Gross).

The Discovery Channel featured this as part of the “A Crime To Remember” series:

https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=Alice+Crimmins+Documentary&&view=detail&mid=7DCA86AA52F0DA2535DA7DCA86AA52F0DA2535DA&&FORM=VRDGAR&ru=%2Fvideos%2Fsearch%3Fq%3DAlice%2BCrimmins%2BDocumentary%26FORM%3DVDMHRS

Man, this made me miss my regularly weekly (sometimes daily in the summer) perambulations now ten years back. I just don’t have the time anymore. Walking is a great way to keep fit and hone your senses. Thanks for sharing this Kevin!

Once again Kevin, you provide a service like no other. This native NYer thanks you.

@Jerry Friedman, I also participated in a 20-mile charity walk when I was in high school, but it was in Manhattan, not Queens, and I think it was for March of Dimes (?). In any case, wearing the wrong socks, I wound up with a blood blister on my foot and had to be half-carried across the finish line…to add insult to injury, when I got on the subway back to my home in Brooklyn, I couldn’t get a seat! Ah, good times.