Restricted by the Covid crisis, or the Great Infection, In May and June, only camera foraging I did was in the neighborhoods surrounding my home in Little Neck, so that pretty much meant Little Neck, Douglaston and Bayside. Beginning in June I expanded things into northwest Queens, with a Long Island Rail Road ride to Woodside, and then in July, I resumed operations in Manhattan. And, during the week the N train is running like a Swiss watch: usually the MTA is loath to run it express in Manhattan, but these days I can get it at Queensboro Plaza and be in Brooklyn in half an hour, so I have roved about in Sunset Park. A NYC Ferry ride also took me to DUMBO recently.

Today, though, I was thwarted when weekend trackwork shenanigans resumed on the #7 train and crowding ensued. I’m not yet ready to risk my health with subway crowds, and thus I aborted today’s scheduled mission to Williamsburg, returned home and took a bike ride instead; I’ll do Williamsburg during the week, if a miracle doesn’t happen and I’m called in for work someplace, at home or away.

In recent weeks I’ve been covering colonial-era Queens roads that have remnants today, such as Laurel Hill Boulevard and Old Bowery Road (Celtic Avenue). Today, though, I’ll be talking about a colonial-era route in western Queens that is actually mostly intact and follows the same route it did in the 1700s. It goes under a variety of names today, but then it was colloquially called Hellgate Ferry Road.

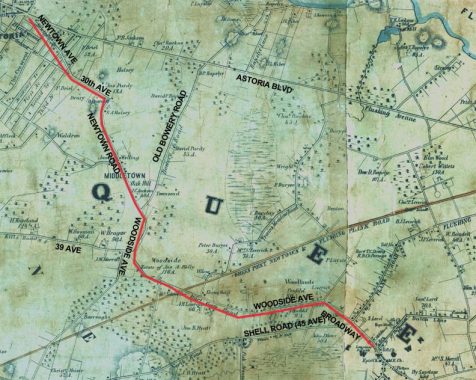

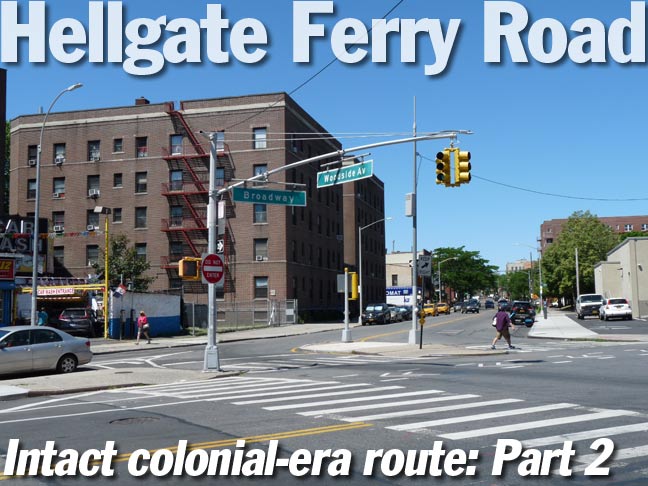

In last week’s segment, I covered the extant portion of Hellgate Ferry Road west of the Woodside Long Island Rail Road station, encompassing Woodside Avenue, Newtown Road, 30th Avenue, and Newtown Avenue. Today, I’ll discuss the remaining segment of Hellgate Ferry east of the station, which includes Woodside Avenue heading east and then Broadway as far as Queens Boulevard. And, the road continues from there: I’ll discuss that section at the very end.

This impressive building at Woodside Avenue and 60th Street with Corinthian pilasters (half columns) opened as the Woodside National Bank of New York in May 1927. A series of mergers, notably with Manufacturers Hanover, Chemical, and JP Morgan Chase ensued.

I have always been fascinated by Irish pubs that are painted in bright primary colors, red in Seán Óg’s case. I had thought that Seán Óg might have been a historic figure in Irish lore, but the name means “young Sean” in the Irish language and has been used by Irish-Fijian athletes and Irish pop singers.

This stolid residential building now known as Queens Landmark, 62-10 Woodside Avenue, used to have a giant clock at the roofline and was built in the 1920s to house the Edward L. Mayer Company, a producer of fine women’s gowns. After a few years, Bulova Watch occupied the ground floor and later, the entire building. Much like the also-lost Swingline Staplers neon sign, the giant clock was a familiar sight for Long Island Rail Road commuters. Alas, the clock is long gone and the building was converted to condos in the 1980s. Bulova Watch also occupied other Woodside buildings and formerly had a headquarters along the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway at the west end of Jackson Heights.

It’s hard to believe it these days, but the LIRR ran at grade through Woodside until 1915, and its curving route still defines some street paths. Additional tracks were added in a grade separation project that year. Because of a hill, the LIRR runs under Woodside Avenue, but is then elevated over Roosevelt Avenue and 61st Street just west of here. All LIRR branches (except the Brooklyn branch) run on these tracks, but the two leftmost separate just east of here and run to Port Washington.

If you think the Winfield Reformed Church, 67-02 Woodside Avenue, was once a private home, it was: here it is in 1940. It still appears much as it did then, despite the large signage. The name of the church is one of the last reminders of a small subneighborhood in eastern Woodside known as Winfield.

Winfield was developed by entrepreneurs G.G. Andrews and J.F. Kendall in 1854 and named for General Winfield Scott (1786-1866), who fought in the War of 1812; the Black Hawk War; carried out the command of his commander-in-chief Andrew Jackson and relocated the Cherokees in the incident known as the “Trail of Tears”; commanded U.S. forces in the Mexican War; ran for President under the Whig banner in 1852, losing to Franklin Pierce; and returned to the military when the Civil War broke out, living long enough to see the Union victory. Scott had moved into a townhouse on West 12th Street in New York City in 1853, and was a New Yorker when the small development in Queens was given his name.

This new building at 69-12 Woodside Avenue is so aggressively Brutalist I have to show it…

…let’s contrast it with some buildings on the north side of Woodside Avenue from a more congenial architectural age, between 71st and 73rd Streets.

“Which way did he go, George”? This sign is erroneously directed. It should face north, as it alerts southbound motorists that 74th Street becomes two-way at Woodside Avenue.

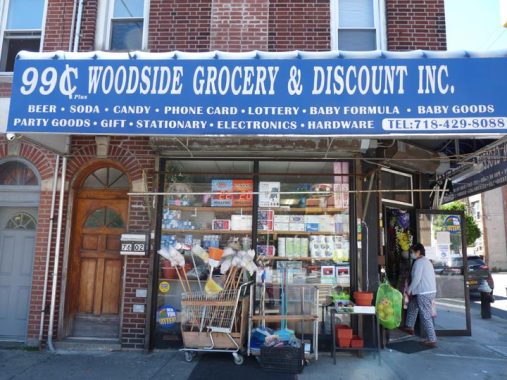

There’s a lot of press lately about New Yorkers moving to places like Vermont or Nevada. You don’t have places like this, at Woodside Avenue and 76th Street, on every corner in those states.

At Baxter Avenue and 80th Street, Woodside Avenue runs into Broadway. In the colonial era, the Hellgate Ferry Road followed Woodside Avenue’s path up to this intersection, and then down the line of Broadway to the heart of Newtown at today’s Queens Boulevard. Broadway itself ran in bits and pieces west to the East River before built continuously when the IND Subway was opened in the 1930s.

City Hospital was founded in the 1850s as NYC’s second municipal hospital at the south end of what was then Blackwell’s Island, which later became Welfare and then Roosevelt Island. After World War II, it moved to its present location at 79-01 Broadway in Elmhurst and changed its name to City Hospital at Elmhurst and then just Elmhurst Hospital. Its present building dates to 1957 though it has had plenty of additions since.

In 2011, doctors at Elmhurst patched up your webmaster after I had cracked my head open on a Metropolitan Avenue bridge railing. I suffer for my art, and everyone else does, too.

One that got away, at Clement Clarke Moore Homestead Park at Broadway and 45th Avenue:

The long history of this site features colonial settlers, a tasty apple, a beloved children’s poem, subway construction, and a neighborhood playground. In the mid-1600s Captain Samuel Moore was granted eighty acres of land in the area to recognize the efforts of his father, Reverend John Moore (1620-1657), in arranging the purchase of Newtown from local Native Americans. Captain Moore built a house here in 1661, and the property was handed down from generation to generation of his descendants. During the Revolutionary War, the British General William Howe made his Long Island headquarters at the homestead. The site is also known as the birthplace of the famous “Newtown Pippin” apple.

Clement Clarke Moore (1779-1863) was the great-great-great grandson of Reverend Moore. Born in New York City, Clement spent much of his boyhood and youth at the family estate in Newtown. He was tutored at home by his father and graduated from Columbia College with a B.A. in 1798, an M.A. in 1801, and an honorary LL.D. in 1829. Moore served as a professor of Oriental and Greek literature at the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan from 1823 until he retired in 1850. Fluent in six languages, he published numerous scholarly works, including a Hebrew lexicon, a biography, and several treatises and addresses. NYC Parks

In the Dirty Thirties, NYC was relentless about bulldozing or otherwise destroying historic properties before preservation laws were on the books, and the Moore homestead didn’t survive the construction of the new IND subway under Broadway in 1933. The land where the house had been became a playground in 1954 and was renamed for the homestead in 1987.

Meanwhile, two Moore burying grounds survive: a hidden one in a playground at 90th Street and 56th Avenue, and the Moore-Jackson Cemetery on 54th Street between 31st and 32nd Avenues in Woodside.

Broadway and Cornish Avenue is the former location of the LIRR Elmhurst station, which closed in 1985. There used to be two intermediate stations between Woodside and Flushing Main Street: Elmhurst and Corona, with Corona closing in the 1930s when the World’s Fair station (now Mets Willets Point) opened, and Elmhurst.

On Broadway between 51st and Corona Avenues is the Reformed Dutch Church of Newtown, built in 1831 and enlarged in 1851 with stained glass added in 1874. It replaced an older structure built in 1733. On the Corona Avenue side is an ancient graveyard with some Dutch-language stones. Some are quite old, going back to the first days of the congregation; the older stones are brownstone with uneven tops, and the lettering in most cases is much more readable than younger marble stones, which deteriorated faster.

Old St. James Church, at Broadway and 51st Avenue, is the oldest building in Elmhurst and among the oldest in Queens; only two buildings in Flushing, the Quaker Meetinghouse and John Bowne House, are older than this building. It is a relic of colonial rule, having been chartered by George III and erected in 1734: it is Elmhurst’s oldest remaining building. It formerly supported a clock tower that a storm blew down in 1882. Last used as a church in 1848, it is now a community center and Sunday school. In recent years the over-260-year-old building has received some much-needed TLC. A ‘new’ St. James, built in 1848, also burnt down; its replacement is an A-frame brick building on Broadway and the NE corner of Corona Avenue.

Across Broadway is the new Elmhurst Library, which in 2017 replaced the original, one of 1,689 free libraries built nationwide between 1883 and 1929 with funds donated by Andrew Carnegie. The Elmhurst branch was opened to the public in 1906 as one of the first Carnegie libraries. The Georgia Revival-style building carried a $46,000 price tag and boasted turn-of-the-century architectural features such as eye windows, balustrades and cornices, most of which have been removed over the years. The new library has less character, but a larger footprint.

This is the beginning, or the end, of Hellgate Ferry Road according to your point of view: in the colonial era, the road fed horse and cart traffic into what was called the Road to Jamaica but has evolved today into a behemoth Queens Boulevard.

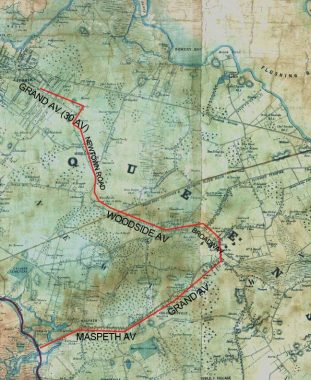

Our story of Hellgate Ferry Road isn’t quite done. If you decide to proceed straight ahead through Queens Boulevard from Broadway you will be on Grand Avenue, a road that continues southwest through Elmhurst and Maspeth and crosses Newtown Creek on a rickety truss bridge built in 1901 (it is slated for replacement) into Brooklyn, where it runs through Williamsburg as Grand Street.

Mitch Waxman, the best night photographer in Queens, runs a site called Newtown Pentacle. It is a theory of his that the Grand Avenue of Astoria and the Grand Avenue of Maspeth are the same route. They are not: but they do have a direct connection. Here, I have reproduced another part of the Matthew Dripps map of Queens from 1852, the oldest Queens map I know of. At lower left, the Maspeth Plank Road crosses Newtown Creek and runs northeast. Parts of this formerly tolled route became Grand Avenue, whose many twists and turns avoided hills and swamps.

The Plank Road ended at the heart of today’s Elmhurst; most of Queens Boulevard had not yet evolved, but today’s Broadway curved northwest, continuing into Woodside as today’s Woodside Avenue, turning northwest past another swampy area into Astoria, where it ran to the East River front along Newtown Road, Grand (30th) Avenue and Newtown Avenue. Thus, these two old routes are linked by ancient roads, most of which are still in place today!

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

9/27/20

4 comments

Great article. Concerning Bulova, they hired a lot of handicapped people to be watchmakers, and were proponents of wheelchair basketball. Not sure if it was this building, probably was, but on Woodside Ave their building even had a basketball court in it, IIRC

When you stated that all LIRR branches go through Woodside, do you mean for those branches going to Penn Station? The Atlantic branch, of course, goes to downtown Brooklyn and does not pass through Woodside.

will amend

— Nice work Kev! — I’m out of 75th St & Woodside Ave — We “played” in the hospital as it was being built! — Originally Elmhurst General — Left the neighborhood in 1985 — For Westchester —