By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

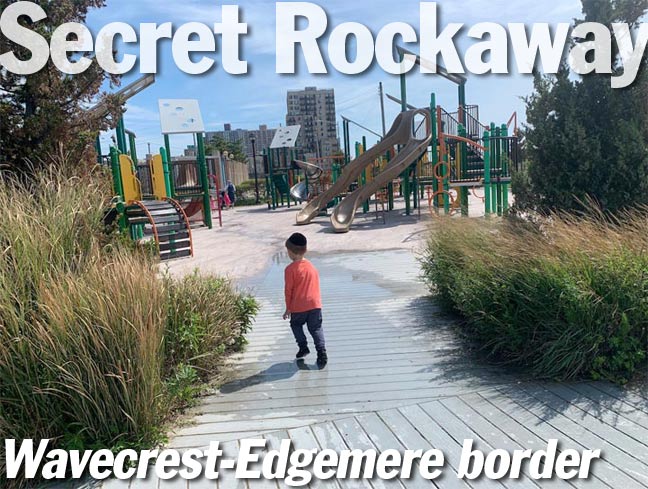

In my search for an exciting park by the ocean, my children have taken a liking to Beach 30th Street Playground in the Rockaways. There are poles for sliding, fountains, stairs, custom design climbing sets, and bright colors within a few paces of the beach and boardwalk. What makes this post-millennial playground worthy of Forgotten-NY is Sandy Road, a one-block street on the playground’s eastern side whose name seems like an unsolicited tribute to the hurricane that walloped New York in late 2012.

Every crisis presents an opportunity and the aftermath of the hurricane resulted in a redesigned boardwalk that serves as a storm surge barrier, and park landscapes that absorb flood water. On the unclear border of the Wavecrest and Edgemere neighborhoods, change is underway with plans to develop the long-vacant stretch of oceanfront between Beach 32nd and Beach 54th Streets, known to city planners as Arverne East.

Kevin Walsh first visited this area in 2005, documenting the site of Edgemere Hotel, the surrounding emptiness, and the remaining bungalows. One example is on Marvin Road, which appears on older maps as part of Beach 28th Street. On my visit in the summer of 2020, five bungalows remain on this street. P.S. 43 is the most recognizable feature on this block, a postmodern brick facility completed in 1996.

Across Beach 28th Street from the school, is the site of the Frontenac Hotel, a name evoking the iconic Quebec City hotel. Historian Emil Lucev estimated nearly 60 hotels in Edgemere at the height of the neighborhood’s time as a summer destination.

The 1919 Hugo Ullitz map shows the Palace and Shelbourne hotels flanking Beach 30th Street. As the neighborhood’s value declined, the hotel became a boarding house, and then a rental property. This last survivor of Edgemere’s glory days was demolished in the 1990s.

Another nearby named road, Spray View Avenue, runs for six blocks, with one of them a few feet off the line on the map. This one-block jog is the only reminder of the palatial Edgemere Hotel that stood here from 1895 through 1935. As hurricanes and currents shifted the shoreline, in its last years the hotel building jutted into the sea. Today it runs through a barren landscape, but it used to have hotels along its length. It is also among the oldest of Edgemere’s streets.

The 1924 city aerial survey shows how the Edgemere Hotel interrupted Spray View Avenue. Also on this map are Seagirt and Edgemere avenues, which would later be broken into two separate segments by Seagirt Boulevard, the major artery running from Edgemere to the Atlantic Beach Bridge. The site of Beach 30th Street Playground had an outdoor bathhouse on it in the 1930s.

Going back further to 1909, we see Spray View Avenue and the grand hotel at its midpoint. On the north side of Edgemere, Norton Inlet nearly cuts to the ocean, almost making the Rockaway Peninsula an island. The streets would be assigned numbers after the peninsula’s annexation by New York City in 1898.

For the first half of the past century, Edgemere was a packed city of upscale hotels, and nearly 100,000 bungalows and tents, but then the automobile, air travel, and suburban housing boom led to the peninsula’s decline as a summer haven. The city declared Arverne East as an urban renewal area in 1965, and had hundreds of homes demolished in favor of apartments that were never built.

The lone survivor on these blocks is P.S. 106, a 1920s structure designed in the style of CBJ Snyder. In Emil Lucev’s book The Rockaways, we see a postcard image of this block where the school is surrounded by homes with porches and bungalows. Today it stands alone. Tomorrow it will again become surrounded by residences and businesses.

A postcard from 1935 from the same location looking north shows the school’s place in the neighborhood, when it was a packed summer destination. At the end of this block, the Edgemere station provided connections to mainland Queens, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the suburbs.

At the merge of Seagirt Avenue and Seagirt Boulevard is a triangle marked with the sign of the Beachside Bungalow Preservation Association, which seeks to preserve the few prewar bungalows in Wavecrest, such as the blocks of Beach 24th and Beach 25th Streets that have dozens of such homes lovingly maintained by their owners and tenants. The organization’s efforts landed these homes on the National Register of Historic Places, which isn’t as powerful as city landmark status that would legally protect them from demolition. Traveling east, Seagirt Avenue separates from Seagirt Boulevard again at Beach 9th Street, near the city’s southeasternmost corner, which I visited in 2010. Edgemere, Wavecrest, Bayswater, and Far Rockaway share the 11691 zip code, which explains the unclear borders between these neighborhoods.

Back in 2003, Kevin dutifully told the stories of the Alleys of Rockaway Beach. At the time, the neo-urbanism of Arverne-by-the-Sea was not yet built, and there was no online official city map to cross-reference his findings. Nearly two decades later, we can add a couple more named alleys to Kevin’s peninsular list of grid-defiant roads. Gartners Court in Wavecrest takes a block between Beach 27th and Beach 28th Streets. It appears on the official map and Google Maps, but does not have a city-issued street sign or a privately-made sign.

On the north side of the elevated train tracks, Gerson Court also appears on both maps, and here it’s clear that this is a private T-shaped dead-end. Its street sign is not city-issued, and the sidewalk continuation on Rockaway Beach Boulevard gives this alley the look of a driveway. Gerson Court and its 13 homes were completed in 2002, making it the newest named alley in Wavecrest. Further north in Bayswater, there are similar privately-built cul-de-sacs and jughandle roads built by private developers. Perhaps worthy of their own page at a future date.

My specialty are the city’s hidden waterways and there used to be a pond in Wavecrest that appeared on maps at the turn of the 20th century. The winding streets of this neighborhood, mansions, and hilltop location indicate its status as a wealthy area. The name was coined by developer John Haven Cheever, who transformed the Clark estate into a gated community for the wealthy. The gates are gone, as is the pond, and most of the mansions. The name is preserved in the subway station and the Wavecrest Gardens apartment complex. The last appearance of the former Wave Crest Lake on a map was in 1919 as a dotted line on the blocks bound by Beach 22nd Street, Camp Road, Briar Place, and Collier Avenue.

Additionally: Lewmay Road takes its name from Lewis H. May, a local property developer who advocated for the peninsula to be its own borough. Until I wrote this essay, I presumed that only Arverne had the distinction of being an acronym of a developer’s name.

From Atlantic Beach Bridge to Breezy Point, the 11-mile Rockaway peninsula continues to fascinate urban explorers and historians.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

9/7/20

5 comments

I know I’m not losing my mind. This particular article was previously posted about three weeks ago

That’s because the site was hacked and had to be restored from a week old backup.

I forgot to note that Lewmay Road takes its name from developer Lewis H. May. So now you know that Arverne isn’t the only place in the Rockaways that’s an acronym of a developer. If not Forgotten-NY, where else could you learn such things?

Re: Wavecrest Pond

Maps from the era show it was drained between 1909 and 1912, with the shape of the streets around it being part of why they have an odd shape

Loved your book “The Hidden Waters of New York City,” Sergey. Nice story and thanks for shouting out Emil Lucev, who did so much to celebrate and preserve the history of the Rockaways. There were many fine accomodations on the Rock, both big and small, but only one ever deserved the title of “grand” hotel–the Rockaway Beach Hotel (also called “The Imperial”), which opened briefly in August 1881, only to be dismantled 8 years later. It’s shown on the map on page 16 in my “Images of America: Rockaway Beach.” Largest in the world at the time, the property spread from Beach 112th to Beach 119th Streets, beachfront to the bay. That is truly “Secret Rockaway!”