All was still normal on Saturday, March 14, 2020 as far as I was concerned, though during the previous week, coverage of the Covid-19 virus was suddenly ramped up to a just-below-frenzy level, and the stock market was selling off like dropping a rock off a table. I took off on what turned out to be my last “camera walk” outside of the Little Neck/Douglaston/Bayside area until June. Just before completing the walk and reboarding the LIRR back to Little Neck, I received a phone call from my pal Heather Quinlan, whose book Plagues, Pandemics and Viruses: From the Plague of Athens to Covid 19 comes out on November 1, wondering what I was doing wandering around in western Queens (I occasionally post pictures from walks on social media) and advised me to go home and don’t come out for quite awhile. Indeed the virus spread quickly after March 14 and peaked in early April.

I haven’t been sick, and resumed walking in June and subway riding in August, though I keep away from crowds (not difficult for me) and wear a mask (which fogs my glasses) whenever I find myself amidst people, which I try to avoid.

This is well-worn territory for me, but I am usually able to find new kernels wherever I go, even if it’s for the dozenth or hundredth time. Also: I was having a little camera trouble on this walk and lengthy zooms are a bit blurry. Bear with me.

GOOGLE MAP: WOODSIDE AND SUNNYSIDE

A look west at Roosevelt Avenue from the stairway connecting the LIRR station with the street. At first I thought these metallic screens were supposed to be catching falling debris from the tracks (a problem along Roosevelt Avenue) but they are actually supposed to be a protective screen from splashing paint: the el structure is getting a fresh green paint job and the work has been continuing through most of 2020.

Woodside and Roosevelt Avenues meet at a tight V, with the small park and sitting area called Carl R. Sohncke Square, named for a WWI Woodsider killed in action.

The NYC Parks entry for Sohncke Square has a capsule Woodside history:

The surrounding neighborhood of Woodside, called “Suicide’s Paradise” by the colonials for its harsh environment, was settled in the late 17th century by Joseph Sackett. Between 1830 and 1860, the area grew and became home to mansions owned by John Kelly, William Schroeder, Gustav Sussdorf, and Louis Windmuller, all men from Charleston, South Carolina. Woodside’s moniker comes from a correspondence written by John Andrew Kelly to his son, John A. F. Kelly, entitled “Letters from Woodside,” inspired by the unending run of trees visible from his writing desk. The younger Kelly, publisher of The Brooklyn Times, printed the letters for the enjoyment of the paper’s readers. Laid out in 1869, Woodside exists today as a patchwork of industrial, commercial and residential areas.

A large sign advising of local Kiwanis Club meetings appears in the square. The Kiwanis Club was organized in Detroit in 1914 by Allen S. Browne and Joseph G. Prance, who began an organization for professionals and businessmen to pool their assets to form a fund for health benefits. Kiwanis soon became an organization for members to promote businesses — the LinkedIn of its day — and also to organize and promote charitable giving. Kiwanis gained enough members for not-for-profit tax status and within a decade boasted 100,000 members. After decades as an auxiliary, women were allowed to join as full members in 1987.

The name “Kiwanis” was adapted from the expression “Nunc Kee-wanis” in the Otchipew (Native American) language, meaning “We have a good time,” “We make a noise,” or, under another construction, “We trade or advertise.” Some persons prefer to pronounce the word “k-eye”; others, “kee.” The organization adopted the name Kiwanis in its second year of existence.

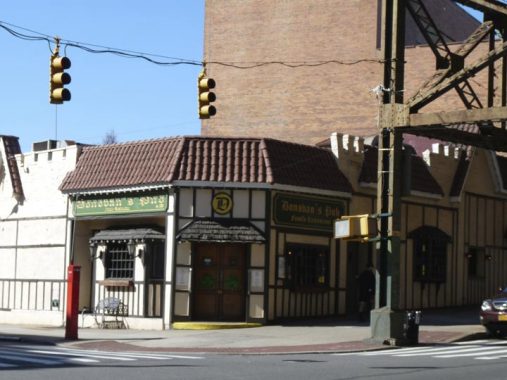

Father and son, Joe Donovans Senior and Junior founded Donovan’s Pub on Roosevelt Avenue and 58th Street in 1966, purchasing and renovating a down-at-heels ginmill called the Clover Leaf. The Donovans added food to the offerings, notably what Time Out New York magazine named “NYC’s best burger” in 2006. The interior is somewhat mazelike, with rooms within rooms behind the upfront bar. The Donovans sold the bar in 2012.

In 1940, Donovan’s was Henry’s Deli.

St. Sebastian’s Church at Roosevelt Avenue across the street from Donovan’s (some parishioners cross 58th directly after Mass to bend the bar) was founded in 1894, with its first services held at the Woodside firemen’s hall at 39th Avenue and 58th Street in a building that still stands, though heavily altered. Two years later its first proper church building was constructed at Woodside Avenue and 58th Street at the former address of a prominent early Woodsider, John Kelly; that building was later replaced by the parish school, which is still standing. A gilded plaque commemorates St. Seb’s parishioners who perished in “The Great War.”

The current church building was once used for much more secular activities: it is the former Loew’s Woodside Theater, a vaudeville and movie palace. It was “converted” in 1952. President Bill Clinton visited St. Sebastian in November 1998 to stump for Chuck Schumer in his successful bid to unseat incumbent Senator Al D’Amato that year.

The parish namesake, St. Sebastian, is usually portrayed as a youth who has just been shot with arrows. According to Catholic tradition, Sebastian was indeed a martyr under the 3rd Century Roman emperor Diocletian, but he was healed of his wounds from the arrows and was later beaten to death with clubs. If at first…

The corner of Roosevelt Avenue and 58th Street is called Martin M. Trainor Way. One of the many honorific streets in Woodside; Martin Trainor (1924-2009), an attorney, co-founded the local organization Woodside on the Move. His law practice focused on fighting for rights of union members and their families. He was active in the Anoroc Democratic Club and St. Sebastian’s Church and a member of Community Board 2. [NYC Honorary Street Names]

At Skillman and Roosevelt Avenues we find Steinmann Triangle, honoring Charles Steinmann, a local soldier who perished in WWI. He grew up at #109 Greenpoint Avenue, since renumbered and renamed as Roosevelt Avenue.

However, Steinmann is not alone in being honored here, as the triangle is also called Richard Trupkin Plaza. Trupkin was a print shop owner and editor of The Woodsider, a community newspaper. He was murdered in a robbery in 1996.

At Steinmann Square is found a pair of octagonal poles now used to hold signs, spotlights, and stoplight control boxes. These poles also used to carry streetlamps before they were replaced a couple of decades ago. However, these two have been adapted for other purposes.

PS 11, across from Steinmann Plaza on 56th Street, admits children from kindergarten to 6th grade. A new annex was built in 2013 after the school reached 120% of capacity.

Woodside’s Queens Library branch celebrated its centennial in 2008. It began as a traveling library collection housed in a general store, designated a branch library in 1910 and moved into its present building in 1937 – which had stood empty for four years during the Depression. It was completely rehabilitated in 2011.

Heading west on Skillman Avenue, walking amidst one of the largest collections of Gustave X. Mathews apartments featuring yellow brick manufactured in Staten Island. Mathews built acres of such housing between 1915 and 1930 in Astoria, Woodside, Ridgewood and Elmhurst.

These Skillman Avenue units were produced for $8000 in 1915 by Gustave X. Mathews, who is virtually unknown today but responsible for much classic residential architecture in Queens. The distinctive yellow bricks were produced in the kilns of Balthazar Kreischer’s brick works in the far reaches of Staten Island. (The Kriescher and Long Island City stalwarts, the Steinways, were linked by marriage.) By 1917, Mathews flats were in such demand that it’s said that if laid side by side the entire string of houses would reach 4.5 miles.

Mathews mass-produced these multi-unit houses for about $8,000 and sold them for $11,000. They did not have central heating or hot water systems. The only heat came from coal in the stove and a kerosene heater in the living room. Despite this, the U.S. Government gave special recognition to Matthews’ concept in 1915 when an exhibit was opened at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. It showed the world how efficiently these type of apartments met housing needs for a surging population.

W & L Liquors, #51-03 Skillman Avenue. There used to be other woodcut sidewalk store signs around town but they’re getting fewer and fewer. I don’t know how long this one has been in place.

A few years ago someone gave the Type 24 Bishop Crook lamps on Skillman Avenue gray highlights on the otherwise black paint job, rather like the fellow who paints fire alarms around town. Actually the work is quite good.

I have patronized a number of Skillman Avenue eateries over the years including the Copper Kettle, at 51st Street, and the Aubergine Cafe, shown here at 50th Street. “Aubergines” are what they call eggplants in England.

Skillman Avenue is westbound for its entire run and ever more traffic-calming measures have been instituted. Sanger Hall is a burgers and brew joint I didn’t know about.

I’d say I have wound up in P.J. Horgan’s about a dozen times over the 27 years since I moved to Queens. However, I have only been in their former Queens Boulevard between 42nd and 43rd Streets (and a few films at Center Cinemas including the second Toy Story). The Queens Boulevard property was sold a few years ago and Horgan’s was forced out, but they reconvened at Skillman Avenue and 49th Street in 2018. Horgan’s was founded November 22, 1963, the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

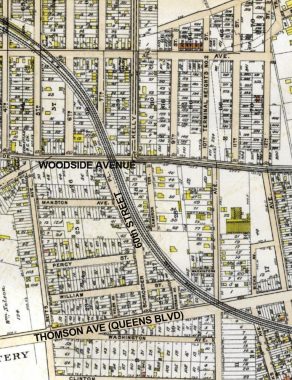

Although Sunnyside’s streets are numbered in the overall Queens system, most of its streets also carry their old names, seen on this 1909 map: Heiser, Gosman, Carolin, Bliss, Grove, Packard, Laurel Hill. This is likely a nod to the MTA’s persistence in keeping the old names of three Sunnyside stops on the #7 train: 33rd Street (Rawson) 40th Street (Lowery) and 46th Street (Bliss).

Meanwhile, Lewis Mumford, longtime architecture critic of The New Yorker, was a cofounder and one of Sunnyside Gardens’ (see below) first residents.

I was unaware of any particularly Turkish strongholds in the five boroughs, but here’s a store selling Turkish brands complete with ads in the Turkish language. Nearby restaurant Sofra was given a favorable review in The New York Times.

Blink and you’ll miss it: Bars frequently change management in Sunnyside and change their names. The Dog and Duck at 46th and Skillman has been given a more prosaic name, The Skillman.

Longtime Sunnyside resident Ethel Plimack (1910-2019) worked for many years with NYC Board of Education and assisted in obtaining Landmarks protection for Sunnyside Gardens. She died at age 107.

Skillman Avenue is at the southern border of Sunnyside Gardens between 44th and 46th Streets; the Gardens extend south to 43rd Avenue between 46th and 48th.

The turn-of-the-century English Garden City movement of Sir Ebenezer Howard and Sir Raymond Unwin served as the inspiration for Sunnyside Gardens, built from 1924-1928. This housing experiment was aimed at showing civic leaders that they could solve social problems and beautify the city, all while making a small profit. The City Housing Corporation, whose founders were then-schoolteacher and future first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, ethicist Felix Adler, attorney and housing developer Alexander Bing, urban planner Lewis Mumford, architects Clarence S. Stein, Henry Wright, and Frederick Lee Ackerman and landscape architect Marjorie S. Cautley, was responsible for the project. Co-founder Lewis Mumford [the long-time architecture critic at The New Yorker] was also one of the Garden’s first residents. The part of Skillman Avenue that runs through Sunnyside Gardens has been renamed in his honor.

The design of the Gardens was novel in that large areas of open space were included in the plan. Construction costs were minimized, which allowed those with limited means the opportunity to afford their own homes. Rows of one- to three-family private houses with co-op and rental apartment buildings were mixed together and arranged around common gardens, with stores and garages placed around the edges of the neighborhood. Just about every interior window in the Gardens offers a view of a landscaped commons. A typical price for a two-story attached brick house in the development cost $9,500 in 1927!

Artists and writers were also attracted to the amenities of Sunnyside Gardens; in fact, the development in its early years was sometimes referred to as the ‘Greenwich Village annex’.” Artistic residents of the Gardens included painter Raphael Soyer, singer Perry Como and actress Judy Holliday. Crooner Rudy Vallee, NYPD Blue actress Justine Miceli, “Rhoda’s mom” Nancy Walker, and tough-guy actor James Caan also lived in Sunnyside.

I had always admired the Gardens, but never lived here. I did, however, move into a smaller facsimile, Westmoreland Gardens in Little Neck in 2007.

Another honorific sign is a block away at 45th Street. Marjorie Sewell Cautley (1891-1954) was a landscape architect who helped design both Sunnyside Gardens and nearby Phipps Gardens. Sewell Cautley designed the Gardens’ superblocks in which houses are oriented around central gardens and linked by footpaths. She was a protegeé of one of the first major female architects, Julia Morgan.

Queen of Angels Church at Skillman Avenue and 44th Street was built in 1965 in place of the Jakob and Katherine Huther house, built before 1900 previously a small hotel used by hunters who hunted in the Sunnyside woods. It was purchased about 1900 by the Hüther family and became their general store and residence. In addition to the general store, Jakob delivered produce door to door with a horse and wagon. He used the pond in the foreground to raise ducks. Above the 44th Street entrance you will find the opening lines of the Magnificat (The Song of Mary). In the New Testament it is spoken by the Virgin Mary upon the occasion of her Visitation to her cousin Elizabeth.

Jack’s Fire Department, Skillman and 40th Street, was featured in the TV show “Bar Rescue” in 2014. Jon Taffer and his crew revamped the 39-46 Skillman Avenue bar in recognition of the firefighting background of the McGowan brothers—all three of whom are current or former firefighters.

The exterior resembles a firehouse—complete with the name: “Lad Co. 39-46 NY.” Inside, the front of a fire engine juts out from the wall accentuating the theme. Furthermore, there is firefighting equipment and various motifs placed throughout the bar. The bar is named for the father of the bar’s owners, the McGowan brothers.

Skillman Avenue looking west along the south side of Sunnyside Gardens from 39th Street. The view is much different from it was just a few years ago, as it has been completely populated with a wall of glassy skycraper residences that have sprouted in Long Island City beginning in the 2010s.

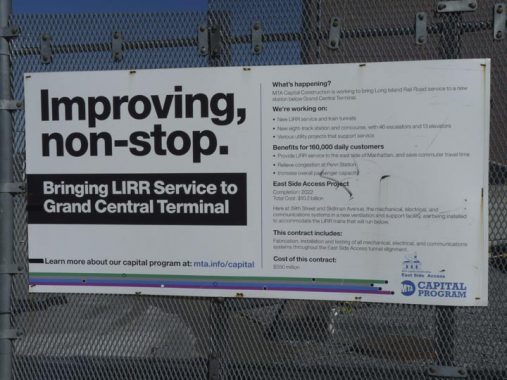

The East Side Access Project, decades in the planning and execution, is supposed to eventually connect the Long Island Rail Road with Grand Central Terminal, which involves finishing a tunnel between Sunnyside Yards and GCT. Initial tunnels used in the project were built beginning in the 1960s below the 63rd Street Subway Tunnel, which now connects the F train on the 6th Avenue Line to the Queens Boulevard Line via Roosevelt Island and 21st/Queensbridge Houses, but much more tunneling has had to be done. Completion of the tunnel has been delayed due to cost overruns and poor planning, e.g. the water table beneath Sunnyside Gardens has complicated the project. Originally due for completion in 2016, the new target date is 2022.

Walking south on 38th Street from Skillman, you espy a break in the solid fronts presented by various factory and industry buildings. The indent is caused by this one lone residence, #41-29 38th, that has survived the years.

I’m unsure if G. Landa and Sons is still located at 43rd Avenue and 36th Street, as Superpages describes it as now located in the Diamond District on West 47th in Manhattan: “…has grown into one of the leading supplier for the jewelry, casting and diamond industries. The name synonymous with the most versatile selection of equipment, machinery, tools and supplies, quality of their services, speediest delivery, technical expertise, and least but not last – competitive pricing.”

If Landa isn’t here anymore, they left behind this plastic and vinyl sign in the ITC font Souvenir, as well as a leftover painted “Furniture” sign from an earlier use.

A pair of huge loft buildings on 43rd Avenue, likely constructed in the 1930s or 1940s. This is an un-Landmarked district, and so their original purposes are difficult to discover. I am aware that the Noguchi Museum (now on Vernon Boulevard) occupied the building with the clock at one time.

Now home to the Prop N Spoon Company, which provides props for retail shows and conventions, and the City View Racquet Club, this building at 32-00 Skillman Avenue which fills and entire block and contains over a thousand windows is the former home of Swingline Staples, founded by Jack Linsky in 1925 as the Parrot Speed Fastener Company, changing the name to Speed Products in 1939 and then Swingline in 1956. The company moved to this new headquarters on Skillman Avenue in 1950 Swingline was famed for its giant neon Swingline staples sign on the roof, featuring a working stapler. In 1998 Swingline eliminated its Queens factory, moving it to Nogales, Mexico. The 60 by 50-foot sign required six men working three ten hour days to pull down.

In 2002 the Museum of Modern Art was renovating its East 53rd street building and moved for a year into another Swingline building on 33rd Street north of Queens Boulevard. In a way, that was fitting because Jack Linsky and his wife Belle were collectors of fine art, including works by including paintings by Rubens, Gerard David, and Boucher. The works were donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and can be found there in the Belle Linsky Galleries. The Linskys were also famed philanthropers, donating millions to charity. But the Swingline jobs have disappeared from the USA.

This brick building in the short block of Van Dam Street between Skillman Avenue and Queens Boulevard is a survivor…the date carved on the roofline reads 1913. The 1940 Municipal Archives photos of the block are silent on the building’s early use, though the building next door used to be home to Mother’s Restaurant and Beer Garden.

This is the only fairly quiet section of Van Dam Street; south of Queens Boulevard, it gains lanes and becomes a busy truck route connecting to the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge over the noxious and noisome Newtown Creek. Van Dam’s conversion and extension came fairly early on in the 20th Century. There’s also a Van Dam Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn across the creek, coincidentally or uncoincidentally: perhaps there was once a plan to connect the two sections.

Returning east on the north side of Queens Boulevard along the el.

This sign for Ridley’s at #34-09 Queens Boulevard is remarkably intact after several decades. It’s a sign for the long-gone Ridley’s candy factory. According to a NY Times article the factory was built in 1923. Whatever happened to Ridley’s, I know not.

Ridley’s was a NYC department store in business between 1848 and 1901; the “est. 1806” mark here would seem to say that this sign is for a different Ridley’s. The department store building can still be found on the Lower East Side.

In the 1940s and on into the 1970s this building was a factory for Breyer’s Ice Cream and it had a huge neon sign for the brand, originated by William Breyer in Philadelphia in 1866, on the roof. Prior to the 1990s Breyer’s was produced with a decent amount of natural ingredients, but this is no longer the case and it has to be marketed in the USA as a “frozen dairy dessert.” The logo has always contained a large leaf; I had always thought it was from a vanilla plant but it’s actually a briar bush (Breyer’s, get it?)

Here’s a look at the Breyer’s sign from the 33rd Street station platform in 1960.

For years the Department of Transportation stored lampposts in a yard on 37th Avenue along Sunnyside Yards, and various experimental types of lamps as well as lamp fixtures were installed on Sunnyside streets south of the yard. The DOT moved the lamps elsewhere in recent years (I know not where) but a legacy of the yard is here on the north side of Queens Boulevard east of 34th Street, one of the City Lights NYC lamppost design contest winners in 2004; I call them the “Harpoons” because of the shape of the mast. True City Lights poles have cylindrical, not slotted, shafts.

As a rule LED luminaires are installed along the bottom of the mast itself, but this one has a Stad fixture installed instead. These were used for a short time in the 2000s before smaller LED lamp makes began to supplant them.

Even motorists don’t think of NYC as having state routes along local streets, but there are a good number in town, including NYS Route 25, which within Queens runs mainly along Queens Boulevard, Hillside Avenue, Braddock Avenue and Jericho Turnpike, and ends up at Orient Point on Long Island’s North Fork. Other state routes that run prominently in NYC are 25A (Northern Boulevard) 27 (Linden Boulevard in Brooklyn) 9 (along Broadway in Manhattan and the Bronx) and 1, along Boston Road in the Bronx.

The DOT has to do triple duty at 40th Street, with signs for the street’s old name, Lowery, and new subname, Lily Gavin, for a prominent local restaurateur who died in 2016.

Ironically the sign has been sunbleached into nonreadability for the 40th Street sign; the DOT traditionally is slow to replace sunbleached signs while replacing perfectly readable ones.

I have been paying more attention to sidewalk signs of late in business and shopping districts, noting the fonts and colors. Here we find another woodcut sign for Maggie Mae’s pub. There were two prominent Maggie May, or Maggie Maes: a traditional bit of Liverpool doggerel sampled by the Beatles briefly on the Abbey Road LP in 1969, and Rod “The Mod” Stewart’s breakthrough USA hit two years later.

A battered 1940s-era directional sign for the Queens Midtown Tunnel at Queens Boulevard and 42nd Street. Circular signs were white or yellow and black and pointed to tunnels, while bridge signs were arrowhead or reverse triangle shaped and colored red, white and blue.

The Edward D. Lynch Funeral Home, founded in 1931, has some impressive frontage along Queens Boulevard east of 43rd Street, including its large neon sign, which still lights up (see the website).

A pair of imaginative storefronts. Usually pizzerias are named prosaically, for the original owner perhaps, but Sotto le Stelle means “under the stars.” The font is Cheltenham Condensed.

Neziah Bliss, inventor, shipbuilder and industrialist, owned most of the land in Greenpoint, Hunters Point, and the small wedge of territory east of Hunters Point centered around Greenpoint and Bradley Avenues called Blissville in the 1830s and 1840s.

Bliss, a protegé of Robert Fulton, was an early steamboat pioneer and owned companies in Philadelphia and Cincinnati. Settling in Manhattan in 1827, his Novelty Iron Works supplied steamboat engines for area vessels. By 1832 he had acquired acreage on both sides of Newtown Creek, in Greenpoint and what would become the southern edge of Long Island City. Bliss laid out streets in Greenpoint to facilitate his riverside shipbuilding concern and according to some records built a turnpike connecting it with Astoria (now Franklin Street in Greenpoint, Vernon Blvd. in Queens); he also instituted ferry service with Manhattan. Though most of Bliss’s activities were in Greenpoint, he is remembered chiefly by Blissville in Queens and by a stop on the Flushing Line subway (#7) that bears his family name: 46th Street was originally known as Bliss Street.

In the 1920s, Queens streets were numbered (for the most part) but the elevated stations at 33rd, 40th, 46th, 52nd and 69th Streets retained the former names Lowery, Rawson, Bliss, Lincoln and Fisk, for the benefit of area oldtimers in the 1920s who remembered the old names. By 2020, there is no reason whatever except tradition to keep the old names!

The Flushing Line Viaduct along Queens Boulevard between Van Dam and 49th Streets is one of the engineering and esthetic marvels of NYC. It was constructed between 1913 and 1917 when this section of Sunnyside was just recently removed from farmland status, and when cross streets along Queens Boulevard were yet unbuilt.

Queens Boulevard looking west from about 55th Street. The view of the King of All Buildings has been compromised by new high rise construction in Long Island, but the Empire State’s pinnacle can still at least be seen.

I like the old Child’s Restaurant at Queens Boulevard and 60th Street so much, with its terra cotta seahorses and other fish, that I posted it on its very own FNY page in May 2020. New development threatens to erase it.

Heading back to the LIRR at 61st Street at Roosevelt Avenue along 60th Street. You can notice a definite bend in the road to the NW just north of 43rd Avenue. Nothing happens by chance with NYC’s street grid…if a street curves, there’s a reason why it did.

If you look at this map excerpt from 1909, the answer is apparent. When 60th Street was still called Schroeder Place (perhaps some kids with toy pianos lived on the block?) it curved to avoid the Long Island Rail Road, which ran on the surface (or as they say in the railroad business, “at grade”) before it was placed in an open cut or on elevated trestles when the present Woodside station was constructed from 1915-1917.

I have always been fascinated by Irish pubs that are painted in bright primary colors, red in Seán Óg’s case, at Woodside Avenue and 60th Street. I had thought that Seán Óg might have been a historic figure in Irish lore, but the name means “young Sean” in the Irish language and has been used by Irish-Fijian athletes and Irish pop singers.

These short brown lampposts (nicknamed “brownies” by me) are usually found in the vicinity of either parks or elevated trains, under which they fit neatly. The fixtures are Holophane bucket sodium lamps, shining bright yellow, houses in a globular casing (nicknamed, also by me, the “new Gumball” since it resembles incandescent Gumball fixtures of the 1940s.

In many places, streets served by the Brownies are giving way to short davit poles carrying modern LED lamps; or else, the LEDs are being fitted onto the Brownies.

Here’s an example of a Brownie fitted with an LED lamp. Time to ascend the escalator to several weeks of lockdown!

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

10/19/20

17 comments

Regarding 43-20 Van Dam Street (which runs through to 31-17 Queens Boulevard): if you compare maps of the area from 1908, 1913, and 1919 and the existing building you’ll find it to be a bit of a Frankenstein. The structure on the Van Dam Street side does not seem to be part of the original structure which was originally composed of a store fronting on Queens Boulevard of one story height with a connected two story (residence?) behind it. There was nothing other than the rear of the building fronting (back 15-20 feet from) Van Dam Street. By 1908 a one story edifice was attached fronting on Van Dam Street housing a “saloon or hotel with bar”. The 1919 maps still shows the Van Dam Street structure at one story, so the 1912 (not 1913) date is a mystery still. (Also weird that the facade above doesn’t span the full width of the ground floor.) An ad from 1962 looking for a commercial tenant indicates that the second floor on the Queens Boulevard side had recently been added.

The LIRR trackage in the Woodside area was relocated and grade separated in 1914-15, including the present station site. Prior to that, the crossing at Queens Blvd. with its six tracks (Main Line and Port Washington Branch) was at grade with gates and watchmen. Imagine that today! The LIRR relocation was no doubt carried out in conjunction with the #7 line elevated, which opened in 1917.

Also note that Route 9 (Broadway) and Route 1 (Boston Road) are US Highways, not NY State routes. The trail blazer signs are different from the NY State signs. Route 1 and 9 enter New York concurrently via the George Washington Bridge, then split at the Manhattan end. Route 9 continues north along Broadway and eventually goes to the Canadian border near Montreal. Route 1 stays on the Cross Bronx Expressway to Webster Avenue, then follows Webster north, to Fordham Road east, to Boston Road north just past the Bronx Zoo. Boston Road carries US 1 all the way through Connecticut and eventually goes to the Canadian border between Maine and New Brunswick. Ironically, US 1 goes right through New Brunswick, New Jersey.

A bit of full disclosure. I am the author of the posting above. I don’t know how “CQU” appeared in lieu of my real name. Must have typed it by mistake. Just want to set the record straight.

The Manhattan location for G. Landa is simply be their corporate offices, streetview of the building shows it to be just another office building in the diamond district with the need to be where their products are going to be used making sense while their manufacturing and distribution is handled at the Queens location…

“Skillman Avenue is two-way for much of its Sunnyside run (with one-way sections in Hunters Point and Woodside) and ever more traffic-calming measures have been instituted.”

Skillman is one-way (westbound) it’s entire length.

I could have sworn it was two way in some sections. I will change that

Haven’t been down there in quite awhile but it was 2 way from around 33rd st to it’s western end at 49th ave

My alma mater-Aviation HS on Queens Boulevard is worth a look. Classic brown brick and green windows architecture of the late 1950s/1960s. Has an actual aircraft hangar in the back by 35th Street and 47th Avenue.

I love Sunnyside! My family has been here since 1975, thanks to my mother! Went to St.Raphaels. Let’s preserve the memories!

Kevin – excellent post as always. Re: Breyers Ice Cream: although it’s not my #1 favorite, I feel like I might need to come to their defense. Coincidentally with your post, my wife purchased a carton “for old times sake” (She knows my parents were big Breyers fans). You state that “Prior to the 1990s Breyer’s was produced with a decent amount of natural ingredients, but this is no longer the case and it has to be marketed in the USA as a “frozen dairy dessert.” But the carton I am looking at right now is labeled “ice cream” and claims to be made from 100% natural cream (from non-hormoned cows) and all natural flavorings.

https://www.google.com/amp/s/champ.gothamist.com/champ/gothamist/news/somebodys-gonna-get-hit-chunks-of-debris-still-falling-from-elevated-7-train-tracks

I was lead to believe the sheeting has been up to catch debris as well. Hmmmm.

The West Shore Expressway on S.I. is NY 440. Forest Ave. used to be NY 439 but those signs have been removed. I think it was from the time when Forest Ave. was the only route to the Goethals Bridge pre- Staten Island Expressway I278.

During the renovation of the Museum of Modern Art, the space where it temporarily located was at 45-20 33rd Street, which is south of Queens Boulevard. In fact, the building is still emblazoned with “MoMAQNS.”

https://maps.app.goo.gl/GEh3zQnQT4qxgQCdA

And that building, I believe, had been a warehouse for Swingline Staplers, when they still actually operated at their plant on the other side of Queens Blvd. Please correct me if I’m wrong.

My father used to tell me about going to the boxing matches in Sunnyside Gardens (?). Anything about that? I also remember going to a German restaurant with the name, if I correctly remember, of Sunnyside Brauhaus.

Ethel Plimack’s death was in 2018. Route 1 in Bronx & Route 9 in north Manhattan, and Bronx are not NYS routes, but US routes. US9’s north terminus is Champlain, New York, Clinton County & US9W at Albany, NY.

Also wanted to add, in addition to NYS 25, 25A, 27, which enter/ exit NYC, NYS 22 does same. NYS 22’s (Provost Avenue) south terminus is at intersection with US 1 (Boston (Post) Road) in Eastchester section of the Bronx. North of US 1, it intersects with East 233 Street, and of course continues due north. It’s north terminus is hamlet of Mooers, NY in Clinton County where it reaches US 11. US 7 in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont completely parallels NYS 22, and of course is connected to east/ west routes in their respective states. These 4 NYS routes are only ones I’m aware of that enter/ exit NYC. I found this that more than piqued my interest: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_Swett