By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten New York correspondent

When city leaders name a park after an individual, we presume that the intent is to eternally honor the namesake with a place on the map and in the minds of park goers. But if one knows where to look, there are examples of parks named after people and then renamed for someone else, or entirely erased. We are not talking here about slave owners or racists being “cancelled,” but simply about changes in public sentiments and failure to remember distant historical personalities.

In Brownsville, Vanderveer Gore was named after a local colonial family, but we know it better as Zion Triangle, given that name in 1925 when the neighborhood had a sizable Jewish population. In the Bronx, Garrison Playground was named after a famous abolitionist, but in October 2020 it was renamed after Evelina Antonetty, a local Puerto Rican civil rights activist.

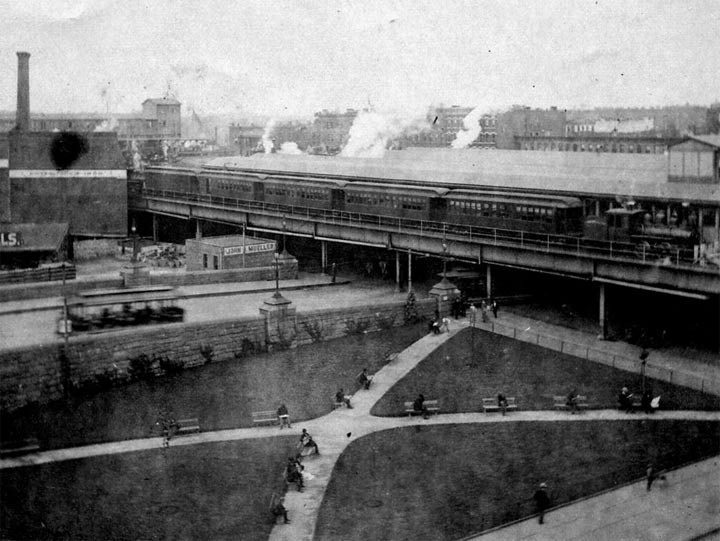

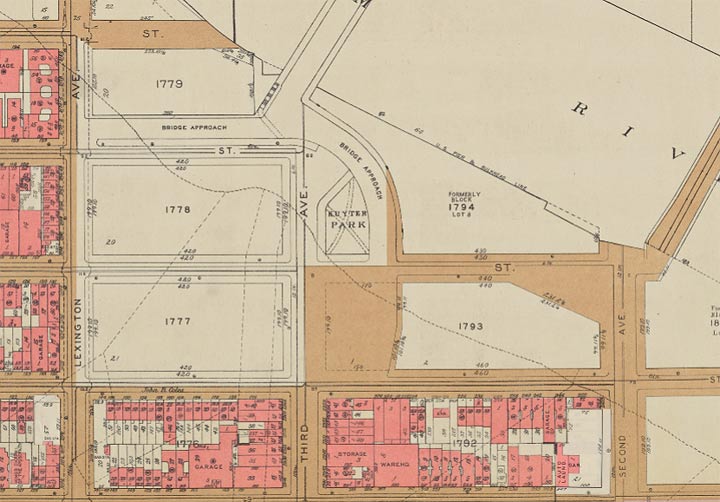

Then there’s Jochem Pieterson Kuyter, whose name was bestowed on an East Harlem park in 1917. This park was located in the shadow of the massive elevated station at 129th Street, where the Second Avenue and Third Avenue lines merged before crossing into the Bronx; and an exit ramp of the Third Avenue Bridge. It had no monument to Kuyter, only benches, grass, trees, and his surname on a sign. The German-born Danish settler sailed up the East River from New Amsterdam in 1639 to establish New Harlem. On the same boat was the Swedish-born Jonas Bronck who established his farm across the Harlem River on land that would later carry his surname. The photo above shows Kuyter Park next to the 129th Street station, from the nycsubway.org collection.

Kuyter was a member of the local advisory council and should be regarded as a positive actor in New York history for protesting colonial Director Willem Kieft’s war against local Natives that occurred between 1643-1645. He is credited with introducing the first Holstein-Frisian cow to America. Ironically, he was killed by Native attackers in 1654.

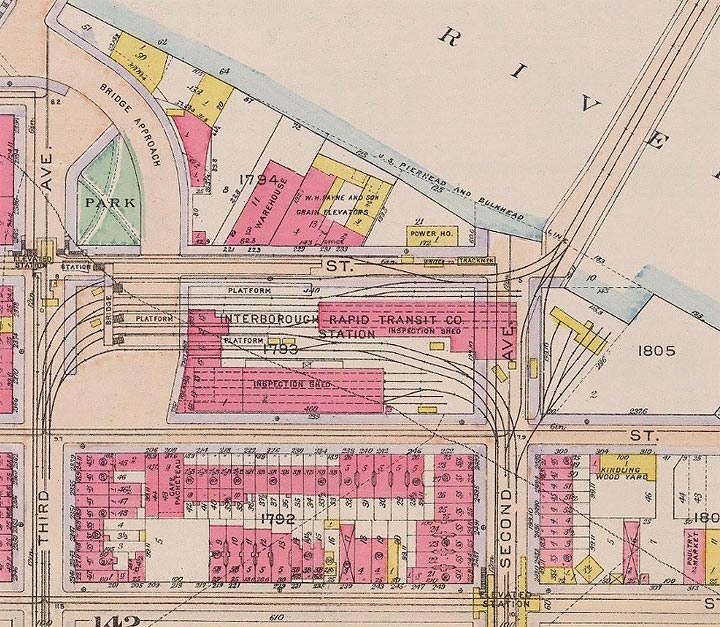

By the mid-19th century, the street grid of Manhattan arrived in Harlem and consumed Kuyter’s 400-acre former Zegendaal (Blessed Valley) estate. In 1878, the elevated trains reached the site of Harlem River Park, with a storage yard constructed on 129th Street. On the water’s edge, coal, grain, and lumber yards relied on the Harlem River as a transportation route, as seen in this 1916 G. W. Bromley map.

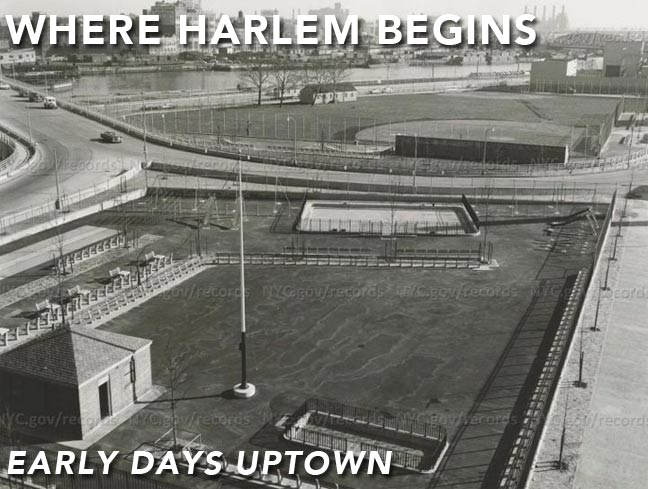

This station was the least used on the elevated line, on account of its proximity to the 125th Street station, and too few homes and businesses next to it. It closed in 1950, five years before the entire Third Avenue El in Manhattan ended service followed by its removal. The site of this station and its storage yard was transferred to the Parks Department which developed Harlem River Park here. This 5.7-acre park absorbed the relatively tiny Kuyter Park and from that point his name was erased from the map. The park’s last appearance on a map was in the 1955 G. W. Bromley atlas.

Third Avenue Bridge received new exit ramps bisecting Harlem River Park, with a section to its west named in 1996 after Alice Kornegay, a neighborhood housing activist. This city archival photo from 1957 shows the newly completed park, playground, and ramps.

With so much traffic running off Third Avenue Bridge, the city installed a footbridge across 128th Street at Third Avenue, providing a bit of the elevated view lost by the removal of the train line. The footbridge has a low railing, no chain link fence, and no lighting.

A block to the south of Harlem River Park is an untitled mural by Valerie Maynard that evokes African art. Maynard also has a mosaic on view at the 125th Street station on the Lexington Avenue line.

Kuyter was the first Danish settler in Harlem. In this century, the neighborhood’s latest great Dane is the Bjarke Ingels firm, which designed a curving facade for 126th Street for an upscale apartment building that has a pool, doorman, rooftop garden, and art displays. Ingels also left his mark on the Midtown skyline with Via 57 West, a pyramidal tower featured on my Riverside South photo essay.

Returning back to the edge of Harlem, Keith Haring’s Crack is Wack mural is as fabulous as when it was completed in 1986, when the Pittsburgh-born artist painted it without permission. Since then, painstaking efforts have been made to preserve his mural from vandalism and natural decay.

A block to the south of this mural is the 126th Street bus depot, which has no distinguishing architectural features other than the wall-mounted street that Kevin first spotted in 1998, shortly after Forgotten-NY was launched. This bus depot stands atop the site of Harlem’s foundation, where its first church, homes, and an African cemetery were located. In 2015, archeologists found human remains under the depot and plans are underway to replace this undistinguished brick shed with a monument honoring the first black residents of Harlem. Born in Congo and Angola, they arrived here as slaves and built the first road connecting New Harlem with New Amsterdam.

The Elmendorf Reformed Church operated this cemetery until the mid-19th century, when it relocated to its present site on East 121st Street. The cemetery was then developed as a pasture, then a beer garden & casino, then a movie studio, then a trolley depot that was repurposed for buses. Plans for the depot envision a mixed-income residential tower with a memorial on the site of the cemetery. Along with the African Burial Ground in downtown Manhattan, the former Schenck Playground in Brooklyn, Drake Park in the Bronx, and Martin’s Field in Queens, it’s the latest example of a black cemetery that was forgotten over the decades and then reclaimed and reconsecrated.

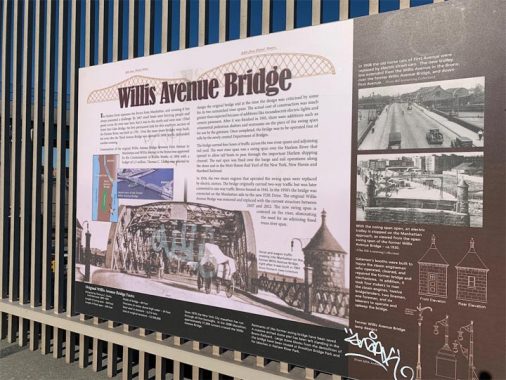

The story of this cemetery and its colonial neighbors can be seen on a historical sign installed on the Willis Avenue Bridge following its reconstruction in 2016. Reflecting the annus horribilis that is 2020, the informative sign has been vandalized with a message of Coronavirus skepticism. No word on whether this vandal survived the pandemic that has killed more than 250,000 fellow Americans.

Another informative sign describes the history of this bridge, that Kevin first crossed in 2009. His crossing involved the original bridge, which functioned from 1901 through 2011. The city offered the old bridge to anyone willing to take it, but no one volunteered. It was then floated to a New Jersey scrap yard.

Bonus points for the bridge lamppost descriptions lower right. —ed.

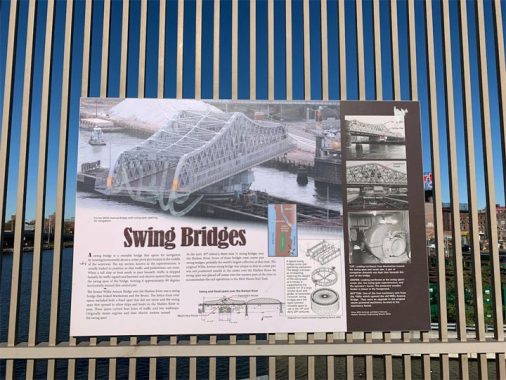

One more sign before I turn back to Manhattan: how swing bridges work. The Harlem River has the largest collection of swing bridges in New York. Flushing Creek used to have two before 1939. Richmond Creek had one before 1931. Lemon Creek had the city’s last human-powered swing bridge. Newtown Creek has one left in 2020.

Looking north on the Harlem River, on the Bronx side is a rooftop advertisement for iHeart Radio. This century-old building previously hosted ads for beer brands long gone, cigarette ads when it was legal to do so, and shows long forgotten. The section of Harlem River between Willis Avenue and Third Avenue had another swing bridge on it, a double-decker that carried Third Avenue El to the Bronx. Along with its two decks of tracks, this bridge had a public walkway. It was removed shortly after the last train crossed it on May 12, 1955.

On the Manhattan side of Willis Avenue Bridge, one can see a pier from an older version of this bridge and a rare trolley wire pole. This section of the shoreline will soon receive a park transformation, connecting the East River Esplanade to the Harlem River Greenway for a continuous shoreline path between Macombs Dam Bridge and Queensboro Bridge.

The bridge connecting 125th Street to Randalls Island, Queens, and the Bronx carries the name of the nation’s 64th Attorney General who also served as this state’s Senator up to his assassination in 1968. Four decades later the state renamed Triboro Bridge in his honor but most New Yorkers prefer to call it by its original name. The DOT dutifully replaced every sign on the bridge with its new name but on 125th Street between its approach ramps the sign notes Triboro Plaza, preserving the old name of the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge.

Looking east from the site of Triboro Plaza, we can travel back to 1798 when artist Archibald Robertson visited the approximate corner of First Avenue and 125th Street. There was a cemetery here next to the church, but unlike the black cemetery a block to the north, this one has not received as much attention from historians. Robertson’s illustration, archeological resources, and maps of this corner as it evolved through the centuries can be found in the 2005 Environmental Impact Statement published ahead of the replacement of Willis Avenue Bridge.

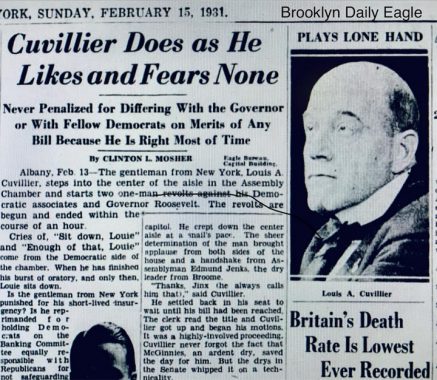

Under the ramps connecting the bridge with 125th Street and FDR Drive is the 2.75-acre Louis Cuvillier Park, named after a State Assemblyman who lived nearby on East 123rd Street. He died in 1935 and this space was named in his honor three years later. At a certain point, perhaps after the connection of the Harlem River Drive to FDR Drive in 1964, this park was transformed into a salt storage and parking for police and sanitation vehicles. Can one imagine a public park amid the tangle of highway ramps? Perhaps as a skateboarding venue, akin to the skateparks beneath Alexander Hamilton Bridge and under Manhattan Bridge, which have the urban appearance favored by skateboarders. Can a former park become a park again? In Tribeca, the story of Canal Park is one such example.

Unknown to today’s Harlemites, Cuvillier was a political maverick who sponsored bills to abolish film censorship and the prohibition. He promoted compulsory health insurance, protection for labor unions, secession for downstate New York, and punishment for cruelty to animals. He also opposed women’s suffrage, proposed capital punishment for arsonists, and expulsion of socialists from the State Assembly. I’m not sure if he would have merited a place on the map if today’s social justice standards were applied.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

11/18/20

2 comments

I met Keith Haring in a bar on 3rd st. around 1980.It used to be a candy store called Sylvia’s back in my day,then became a bar.He was interested in you know what but me no gay.Then what was I doing in a gay bar if I’m straight?I guess because I hadnt seen the sign outside that said”Gay Bar” before I entered

Third Avenue and Willis Avenue Bridges are unique in New York because they are a one-way pair. The Third carries southbound (Manhattan-bound) traffic; the Willis carries northbound (Bronx-bound) vehicles. Originally both were conventional two-way crossings, but were converted to one way operation on August 5, 1941 to ease traffic congestion in the vicinity. As part of the conversion, the Third Avenue Railway System (not the elevated, but streetcars) converted a major streetcar route to bus (today’s BX15) in order to facilitate the changeover.