Today in Forgotten NY, we’ll talk about a place I’ve never been to. But Sergey has…. –Ed.

BY SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

On the colonial landscape of Long Island, the town seats of Jamaica and Hempstead had an identical history and appearance. Both were founded during the Dutch period by English settlers fleeing the harshness of Puritan rule in New England. Both were built within a grid of streets and included a prominent church, courthouse, Town Hall, lawn in the center, and both serve as transit hubs. While Jamaica became more urbanized after being absorbed by New York City, Hempstead’s urban core emptied out as a result of suburban sprawl and shopping malls that took away the commerce, residents, and visitors from this “urban” village. Much of the space in downtown Hempstead consists of parking lots that could be redeveloped in the future as a transit-oriented community.

The Art Deco-style Telephone Exchange was completed in 1930. It appears familiar to city dwellers because it was designed by Ralph Walker and the firm of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker. The same team also built the Barclay-Vesey Building in downtown Manhattan, the Long Distance Building of A T & T at 435 West 50th Street in Hell’s Kitchen, 206 West 18th Street in Chelsea, the landmarked Long Island Headquarters Building in Brooklyn, New Jersey Bell Headquarters Building in Newark, Western Union Building in Syracuse, and the telephone exchange in Rochester.

A closeup of the Telephone Exchange shows an elaborate floral relief similar to the Midtown’s Chanin Building, which was completed a year earlier. There’s a site documenting all of the architecturally distinct and still functioning telephone buildings in Nassau County, the outer boroughs, and Manhattan. See how many Art Deco facilities you can find. Ralph Walker was synonymous with the New York Telephone Company as CBJ Snyder was to public schools, and Squire Vickers to subways.

The post office for Jamaica is a Federal Revival design relating to the early years of this republic. Hempstead’s post office is stylistically a blend of Jamaica and Forest Hills, built during the Great Depression, with an interior mural of the same local history realism as the one at Flushing. For more postal architecture, the Postmark Collectors Club has a Flickr album of every post office building in the state.

Jamaica’s Town Hall was unceremoniously demolished in 1940 while Hempstead’s town seat is a complex of historical revival and modernism. Hempstead Town Hall was completed in 1919, with Philadelphia’s Independence Hall as its inspiration. Behind it, Mill River flowed across a public lawn on its way to Hempstead Lake. In this undated photo from the Hempstead Library collection, we are looking south across the future Town Hall plaza towards Hempstead Lake.

At the time, it was known as Harper Park, as seen in this map from 1914. Jamaica’s center is framed by Hillside and Jamaica Avenues, Sutphin and Parsons Boulevards. Hempstead’s colonial grid is framed by Front, Clinton, and Main Streets, and Fulton Avenue. A century ago, Jamaica Avenue was also named for Fulton, an early 19th century New York celebrity best known for his steamboat. The portion of Mill River running through Harper Park appeared on some maps and photos as Horse Brook, the same name as the phantom stream that flowed through old Newtown (present-day Elmhurst).

Jamaica has Ashmead Park as an example of a shrinking green space, and Hempstead had Prospect Park that was shrunk by the widening of Peninsula Boulevard and the construction of a pumping station in the past decade. Looking west from the site of Prospect Park, you’d think that this was somewhere in NYC. Between the apartment buildings one can see the old and new Hempstead Town Hall. Prior to urbanization, Mill River flowed through this scene.

From the village’s archives, here’s a view of Prospect Park in 1970, with Peninsula Boulevard diverging from Fulton Avenue. Once known as Prospect Street, it was widened in the 1950s and extended to the Five Towns as Peninsula Boulevard. At that time, Nassau had a system of County Roads marked by unique orange signs, the same color as the county flag. Peninsula Boulevard was marked as County Route 2. When federal regulators required all counties nationwide to use blue colored route signs, the budget-conscious county lawmakers decided to retire the numbering system.

In the 1960s, it was covered up in favor of the town’s office building, the Nathan L.H. Bennett Pavilion and a sizable parking lot. The plaza facing these buildings was named for Councilwoman Dorothy Goosby in 2021, honoring her role in civil rights advocacy and the elimination of at-large town districts that suppressed minority voters.

Across Peninsula Boulevard from Town Hall Plaza is an old house whose style was common across the village two centuries ago. Serving as the rectory of St. George’s Episcopal Church, it was the birthplace of industrialist Edward Henry Harriman.

On the north side of the old Town Hall is the Cooper Field parking lot, named in honor of Peter Cooper, the inventor and industrialist who drained Sunfish Pond in Manhattan, caused pollution in Newtown Creek, and also lived in Hempstead for a time. His son Edward served as Hempstead’s village treasurer and fire chief and this field used to be his property. I can imagine this “parking crater” across from the town seat transformed into a residential and retail complex evoking an actual town square, but for now cars rule the townscape.

Every historic town center has its steepled church in the center. Downtown Flushing has St. George’s Episcopal and Jamaica has Grace Episcopal. Flanking Cooper Square are St. George’s Episcopal and the taller United Methodist Church whose white exterior resembles the Reformed Church of Newtown in Elmhurst. The tallest steeple in Hempstead today belongs to the Roman Catholics, St. Ladislaus Church, which serves the town’s Polish community.

With Harper Park a distant memory and Cooper Square covered by parked cars, there is another sizable public space in downtown Hempstead: Denton Green. If it feels empty for a park, that’s because it is a former cemetery that still has a few documented graves under its lawn and a couple of tombstones. The park’s namesake is the Rev. Richard Denton, who founded the settlement in 1644. In Jamaica, the big green space in the urban center is Rufus King Park, which has a historic house, sports field, and playground.

The term village evokes a rural or bucolic setting, but legally it is a unit within a town that has a defined amount of autonomy from the town concerning taxation and services. Within the Town of Hempstead is the Village of Hempstead. Its seat of government is on the north side of Denton Green next to the village’s public library which is pictured here. Both have nice lawns in the front and enormous parking lots in the back.

In total, there are 22 villages within the Town such as Cedarhurst, Freeport, and Malverne. Additionally, there are also 38 hamlets or communities administered directly by the Town, such as West Hempstead, Wantagh, and Woodmere. Garden City isn’t an actual city, but a village within the Town, while the Five Towns are merely a nickname, not an actual administrative unit. There are two actual cities on Long Island: Glen Cove and Long Beach, but the Town of Hempstead far exceeds them in population and size.

On the northwest corner of Denton Green is Station Plaza, a street where trains once ran. The town’s first train terminal opened in 1872 on Fulton Avenue near Main Street. In 1942, the tracks were pushed back to its present site at Columbia Street. Portions of the tree blocks were redesignated for a parking lot, Station Plaza, and the town’s bus terminal.

The present train terminal headhouse was completed in 2002. It features a clock and a public artwork, Ron Baron’s Lost and Found: A Hempstead Excavation Project. The station offers direct service to Brooklyn’s Atlantic Terminal with a few trains to Penn Station. A century ago, it was possible to take a train from Hempstead to points east via the old Central Branch, and north to Mineola and Oyster Bay via Hempstead Crossing. Indeed, a century ago, there were more transit lines in the city and on Long Island than today.

Baron’s sculpture captures a moment in time. Looking closely, one can see a bulky laptop with a floppy drive between the briefcases, and a model of the M1 rail car that was retired from service in 2007. Initially Baron’s column was framed by sculptural seats that resembled suitcases but for some reason, the MTA had them removed.

Like Jamaica, downtown Hempstead is a majority Black community and names relating to the civil rights struggle appear on its map. While Jamaica’s 165th Street Bus Terminal is a long walk from the LIRR, the one in Hempstead is across the street from the trains. It carries Rosa Parks’ name as she personified the effort to end segregation in public transportation. Also concerning Black history, Jamaica has a street named after the Tuskegee Airmen, and so does Hempstead.

At the corner of Columbia and Main streets is an old Tudor revival building across from a post-millennial brick apartment building. This building stands alone but perhaps soon it will have equally tall neighbors as urban renewal plans move ahead. A more creative contemporary can be seen at 303 Main Street, an upscale tower with urban amenities such as a private garden, game room, and outdoor pool. I don’t expect Hempstead to gentrify with the same intensity as western Queens, let alone Jamaica.

Jamaica has its county courthouse and so does Hempstead. The appearance of the District Court at 99 Main Street is extremely uninspiring as are the rows of law offices across the street. But Hempstead is not the County Seat and most of the courthouses, public agencies, and legislature for Nassau are in Mineola. Similarly, Jamaica is an urban hub but the Borough Hall for Queens is in nearby Kew Gardens.

At 80 Main Street the words Nassau Garage appear prominently on the facade. A century ago when cars were new and few, dealerships and garages had a fancy look to them. In this historically Black neighborhood there is now a growing population of immigrants from Mexico and Central America, evident in the Spanish-speaking businesses on this street.

At 58 Main Street is Mr. Tacos, a Mexican restaurant but at its entrance is a plaque commemorating Sammis Inn, where President Washington was hosted on his 1790 tour of Long Island. After 223 years or seven generations, the Sammis family gave up their tavern in 1902. Plaques honoring Washington’s tour can be found across Long Island, and you can follow his route in Joanne Grasso’s book that follows his route. I can’t imagine that Mr. Washington had ever tasted a taco, but 44 presidents later another one tweeted about it.

Besides the telephone building, perhaps the other leading urban-style structure in this village is the former Bank of Hempstead, a beaux arts beauty completed in 1909. Sadly it is vacant at this time.

The side of the bank facing Fulton Street is a parade of nine arches on this busy road. Designated as New York State Route 24, it is known as Hempstead Turnpike to the east and west of Hempstead Village. The other major route framing downtown Hempstead is Front Street, which is New York State Route 102, one of the shortest numbered routes in the system.

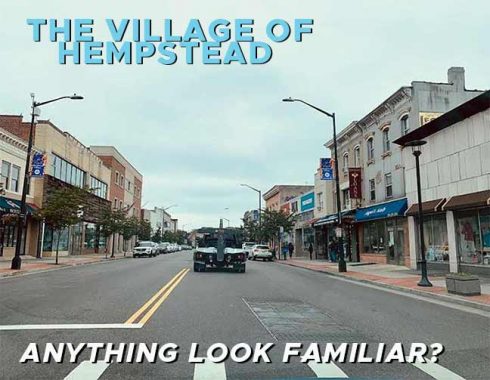

Looking south on Main Street, the view can substitute for any outer borough commercial strip. The cornices are reminiscent of Brooklyn, but rare on Long Island. I’ve seen them in a few upstate downtowns and they remind me of NYC. There’s a bike shop on this block, but it will be a long time before Nassau County will have a bike route network as extensive as in the five boroughs. Prior to the mid-1920s, a streetcar line ran on Main Street.

As mentioned, the rise in private car ownership in the mid-20th century not only resulted in the elimination of streetcars, cutback of train service, and endless parking lots, but also the demapping of streets in favor of parking. Looking north on Orchard Street near the Telephone Exchange, one would never guess that a stream flowed across this scene prior to urbanization.

In an undated photo from the Hempstead Public Library we see the same scene, Orchard Street at high Street as a suburban community, with an Abraham & Strauss truck making the deliveries. A precursor to the ubiquitous Amazon vans of today.

As with my previous essays, historic maps tell the story of urban development. IN this Beers Atlas plate from 1873, we see the village center framed by tributaries of Mill River, designated as parkland at the time. The ponds formed by this creek were used by gristmills and for ice harvesting. On the south side, a proposed train line appears but in the end, it was routed through West Hempstead. Denton Green appears as “Old Town Burying Ground.”

Continuing to 1914, we see much of the farmland and estates surrounding the village under the ownership of residential developers who anticipated the suburban boom. In orange, I highlighted the portion of the west Hempstead Branch that used to run north to Garden City and Mineola. It was abandoned in the 1960s. A smaller orange line shows the original extent of the Hempstead Branch that is today’s Station Plaza.

The oval circle on the far left explains my interest in Hempstead history. In 2017, I purchased a house on a bend in Poplar Street and I was instantly curious why that street was making its curve past my property. The answer is that it was an old farm boundary. Unsure If I was ready to leave my beloved Queens for suburban life, I rented out the house and occasionally visited my tenants. When repairs were needed, I drove to the Home Depot in downtown Hempstead and was fascinated by this center of urbanity on a plain of capes, colonials, and ranches.

The 1926 aerial survey from the county’s records shows the street grid with the major roads and Mill River highlighted. At the time, nearly all sidewalks in Hempstead were lined with trees in contrast to today’s concrete “village.”

Before I leave Hempstead for the familiar streets of Queens, I’ll share one more comparison between this urban village and downtown Jamaica. The corner of Fulton Avenue and Bennett Street on the east side of the village used to be the home of horse racing magnate August Belmont. In the middle of the last century, it served as an Elks lodge. As was done in downtown Manhattan, the village put Elk Street on the map behind this property.

Looking east on Elk Street today, the mansion’s site is a nondescript apartment building managed by Zara Realty, whose red triangular building entrances adorn dozens of buildings in downtown Jamaica. In the background, the village end and Uniondale begins with its single-family homes that exemplify suburban Long Island.

It is rare for Forgotten-NY to venture far beyond the city’s borders, mostly it is limited to one-shots and neighboring municipalities. Kevin has been to Great Neck, Hoboken, and Fort Lee. Further afield, he’s documented the alleys and lampposts of San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Washington.

One should keep in mind that in 1898, Hempstead had the opportunity to give up its Town & Village status and become part of NYC. In a county-wide referendum, the residents rejected the idea. Had it passed, perhaps I’d be walking down 305th Street in Hempstead instead of Main Street and Kevin would be spending more time out here.

——————

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

10/7/21