UNFORTUNATELY, though I feel fine in general, I am unable to walk for any great distance without pain and discomfort (I’d rather not provide any more detail) and so, I’ll be leaning on my photo collection for the time being; fortunately, my photos number around 700,000 in my estimation. Not an optimal circumstance; I’d rather be out in the field, grabbing new images, and I’d even like to resume live tours at some point, but I need to resolve “this thing” before that happens…which hopefully will be in 2023. Bear with me if I occasionally recycle material, which is quite normal as I go into the 24th year of Forgotten NY. Things are looking up otherwise, as I was rehired as an editor by Marquis Who’s Who fulltime after a few months on the freelance taxi squad. Best of all I am able to work from home, though my work hours are more tightly specified and regimented as a “salaryman.”

In January 2022, a very cold month (fine by me unless it’s windy), I took the train down to the Battery and snapped off some images in Battery Park City and along the waterfront, and then headed north to Tribeca, finishing at 6th Avenue and Canal.

I had no idea that a new pedestrian bridge spanning the pedal-to-the-metal West Street (formerly the West Side Highway) opened during 2021; like the new Denny Farrell Bridge in Washington Heights, I didn’t know it existed until I saw it. It was constructed in tandem with the new 64-story residential skyscraper, 50 West and connects JP Ward Street (a tiny thoroughfare at the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel) with West Thames Street in Battery Park City.

The Architectural Record calls the Robert R. Douglass Bridge “the last piece of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation’s (LMDC) plan for rebuilding and restoring the area below Houston Street affected by the destruction of the World Trade Center towers.” That’s quite a claim! The lenticular truss bridge took 7 years and $45 million to complete and is the handsomest of the pedestrian spans across West Street with the possible exception of the bridge at Chambers Street leading to Stuyvesant High School. The bridge was named for the late head of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation.

The Douglass Bridge was fabricated in metal shops in New York and Pennsylvania and assembled in Red Hook, Brooklyn until it was ready to be positioned, and was moved by barge up the bay to West Street. An open design permits views up and down West Street (but that means it’s cold in the winter there). Best of all, it doesn’t sway like Brooklyn Heights’ old Squibb Bridge, so no seasickness will result from crossing it.

[50 West is a] 64-story tower designed by Internationally acclaimed architect Helmut Jahn features unparalleled views of the New York Harbor, the Hudson and East Rivers, the Statue of Liberty, and Ellis Island. The approximately 780’ skyscraper features floor-to-ceiling curved glass windows. Thomas Juul Hansen has designed and finished the expansive interior layouts, ranging from one to five bedrooms and featuring an array of duplex and double height spaces. [StreetEasy]

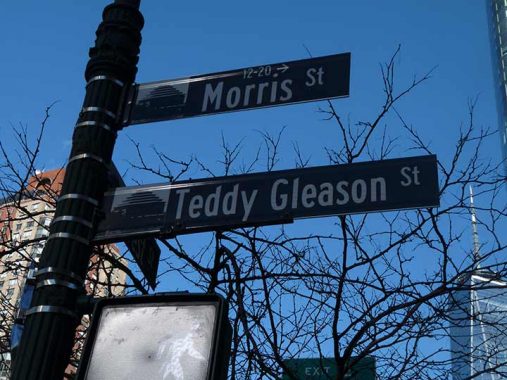

I have liked the black and white Downtown Alliance street signs since they began appearing in the Financial District around they year 2000, each contains a photo of a local landmark, whether it is still standing or has been torn down. I wish this design would be used all over the city, though I imagine it would incur some expense.

If you look at a map of lower Manhattan there are, in effect, two Morris Streets, one between West and Washington Streets and another between Greenwich and Broadway. The two were once continuous, but the construction of the Hugh Brooklyn Battery Carey Tunnel in the 1940s severed it into two nearly equal halves. The city recently subnamed the western section for Teddy Gleason, president of the International Longshoremen’s Association from 1963 to 1987. Lower Manhattan used to have a working waterfront.

On either side of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel bell mouth, on Washington and Morris Streets on the west side and Greenwich and Morris Streets on the east side, there are a batch of original Corvington streetlamps that were likely installed between 1920 and 1940. Though the Morris Street Corvs had been saddled with yellow sodium lamps since the 1980s, in 2020 they were finally supplied with more historically accurate Bell fixtures with bright white LED bulbs.

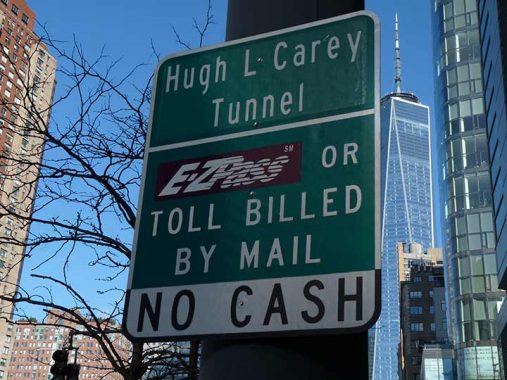

NYC politicians, most of whom are in the Democratic Party, enjoy honoring their own by appending names of deceased politicians to bridges and tunnels that have been known by one name for decades and have been so fused with the engrams of New Yorkers that they refuse to use the new ones; hence, the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel, named in 2010 for the twice elected NYS governor and longtime US Representative who presided through the economic crisis of the 1970s, for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel (completed in 1951 after a delay due to World War II). It’s hard to imagine it now but the Brooklyn Bridge, which doesn’t allow truck traffic, was once the southernmost point for motorized transit between Brooklyn and Manhattan. On the other hand, LaGuardia Airport (named for a Fusion/Republican mayor) stuck, in place of the old North Beach Airport/Glenn H. Curtiss Airport/Municipal Airport 2 names. It didn’t hurt that LaGuardia was still alive and serving as mayor when the airport was renamed, and had refused to land at Newark Airport after an out of town trip and demanded to land at far-flung Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn instead.

Other new names that mostly go unused: Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (Triborough); Ed Koch Bridge (Queensboro/59th Street Bridge); Mario Cuomo Bridge (Tappan Zee Bridge). New Yorkers were also so adamant about not using “Avenue of the Americas” instead of 6th Avenue that 6th Avenue signs were finally added during the 1980s.

One of these days, or one of these years, I will take an in-depth look at Battery Park City, which is on landfill west of West Street…on the only New York City streets located west of West. It was first proposed in 1966 and began construction 10 years later; the southern stretch of landfill was from excavations for the first World Trade Center, while the northern end came from dredgings of the Ambrose Channel off the New Jersey coast. Over the years, Battery Park City has added such attractions as the Skyscraper Museum, Museum of Jewish Heritage, Irish Hunger Memorial, Teardrop Park, Nelson Rockefeller Park (Republicans got a name here) and Pier A. To be honest, whenever I’m there I find its 1980s architecture something of a snoozer.

I am ever grateful to live in a “city of water.” I have not been on Liberty Island since a Cub Scout trip in 1965 and, while I have no intention of climbing the statue’s cramped staircases and even more cramped vantage points, I think I will put getting on a boat with the rest of the tourists to Liberty Island on the to-do list.

It’s also been too many years to count since I’ve been in Liberty State Park in Jersey City in which you will find the preserved RR station serving the Central Railroad of New Jersey. The Richardson Romanesque building served as a railroad terminal from 1899 through 1967; ferries brought passengers to NYC across the Hudson River. Today, ferries bring tourgoers to Liberty Island from the terminal.

The familiar octagonal Colgate clock, facing Manhattan and visible from the Wagner Park riverside walk in Battery Park City, dates back to 1924 when it was set in motion on December 1 by Jersey City’s Mayor Frank Hague. Located on the former site of Colgate-Palmolive & Company, it is a reminder of the time when factories dominated the Jersey City’s waterfront. The clock’s design was inspired by the shape of a bar of Octagon Soap, first manufactured by Colgate as a laundry cleanser.

The Colgate‘s Soap and Perfumery Works, later Colgate-Palmolive Peet, was founded by William Colgate in 1806. He began as a manufacturer of starch, soap and candles with a shop on John and Dutch Streets in New York City. When he moved his company to Paulus Hook (Jersey City) in 1820 to produce starch, it was referred to as “Colgate’s Folly.” The company instead flourished and had a sizable complex in Jersey City by 1847. It made chemically produced soap and perfume but eventually gave up perfume production. Upon the death of William Colgate in 1857, his son Samuel reorganized the company as the Colgate Company. It took on brand products such as Cashmere Bouquet, perhaps the first milled perfumed soap, and revolutionized dental care with toothpaste sold in jars in 1873. It also packaged toothpaste in a “collapsible” tube in 1896.

Overlooking the Hudson River, the octagonal Colgate clock and signage perched on a company structure remained unaltered until 1983. The signage “Soaps-Perfumes” was removed and a toothpaste tube, advertising one of Colgate’s best selling products, took its place. Two years later and after 141 years in Jersey City, Colgate decided to leave, citing the need for improved facilities that its original manufacturing complex could not provide. The entire complex was razed, and the clock, without the toothpaste tube, was lowered to ground level as a freestanding icon on the future Goldman Sachs property, where it stood for fifteen years. The 24-acre site became part of the redevelopment of the Jersey City waterfront at Exchange Place that began in the early 1990s.

The clock was dismantled in June 2013 and refitted with LED lights, and then reinstalled on the waterfront near the Goldman-Sachs Building.

A return trip to Jersey City is also on the hoped-for agenda in 2023. I have done several Forgotten NY pages in Jersey City and Hoboken, infuriating some readers who believe that Forgotten NY should always be about the five boroughs. Not being able to drive or possessing a car, I do not leave the city as often as I’d like, but my absence from areas outside NYC is not intentional on my part.

This photo features the two tallest buildings in New Jersey, the Goldman Sachs Tower (30 Hudson Street) on the left and 99 Hudson Street, 79 stories and 900 feet in height, to its right; it took the title from 30 Hudson in 2019. Not to be outshone, New Jersey’s 4th tallest building, URBY Harborside Tower I, is off to the right.

Among Battery Park City’s highlights are its numerous parks, along with a magnificent waterside promenade. Rector Park and its sculpture, Rector Gate, opened in 1988.

I had thought for a long time that the climate controlled atrium in the World Financial Center (officially called Brookfield Place) in Battery Park City was the only place outside of the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx that you could find palm trees in NYC, but I discovered other palms in another atrium at #60 Wall Street, as seen on this FNY page. Every year, a contest called Canstruction challenges teams of architects, engineers and contractors to build sculptures made entirely out of unopened cans of food. The large-scale sculptures are placed on display and later donated to City Harvest to help provide families with a holiday meal.

Battery Park City’s main north-south routes and North End and South End Avenues, north and south of the World Financial Center, and its east-west streets are western extensions of Rector, Thames (called West Thames), Albany, Liberty, Vesey, Warren, Murray and Chambers streets. Additionally, on the south end of BPC, three new numbered streets were created: 1st, 2nd and 3rd Place. On the west end, River Terrace extends from Vesey Place north to Chambers Street.

Type B park lampposts, first designed in 1912 by architect Henry Bacon, are nearly ubiquitous in parks and are used extensively in Battery Park City. Here on South End Avenue, though, the concept is stretched to its limit as a post is tricked out with spotlights and a J-shaped fire alarm indicator at a taxi stop on South End Avenue. The alarm lamp has not been serviced for over a decade, but they remain in place nonetheless.

Unlike, say, Washington, DC or Los Angeles, NYC doesn’t have much of a tradition of post-top streetlamps. This, at the northern end of South End Avenue at the World Financial Center, is an example of what form post-top streetlamps could have taken if they were widely used here. A Corvington-style base and shaft is crowned with five park post lamps.

As stated previously Battery Park City is populated by retro versions of the classic Corvington and Bishop Crook poles, seen here, with Type B park lamps deployed along side streets in addition to their usual role in parks. Battery Park street signs are unusual in that they are smaller versions of the usual green and white vinyl signs; they were also used along West Street north of Battery Park City. Many are now being switched out to normal sized signs with upper and lower case lettering.

Built in 1994, the Tribeca Bridge, or Chambers Street Bridge, is the oldest of the three remaining West Street crossings from Battery Park City and enables easy crossing for Stuyvesant High School access across the pedal to the metal West Street traffic.

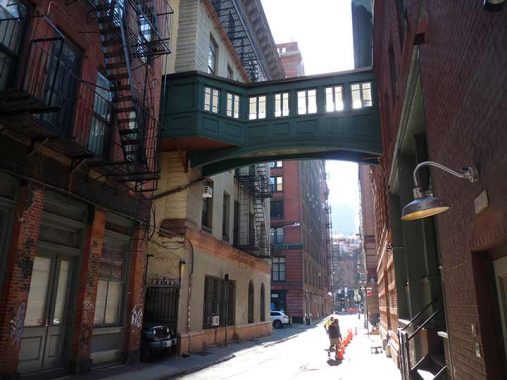

As you might have expected, I wandered over to Tribeca’s most evocative alley, Staple Street, for some pictures. I am usually here when the sun is higher in the sky but today, in January, I found the shadows and their interplay with the Belgian blocked cross streets as well as the shadows cast by the Staple street Bridge to be interesting and visually stimulating. For midsummer Staple Street photos, see this FNY page.

As I stated on that linked page, some sources, such as Henry Moscow in Hagstrom Maps’ The Street Book, say that the name refers to the unloading of goods, or “staples” to the numerous markets that were located in the Lower West Side beginning in the Dutch colonial era. However, the NYC Landmarks Designation Report for Tribeca West disputes that derivation and prefers the explanation that most of the streets in this area refer to political figures, local prominent residents or people associated with Trinity Church, and notes that a John J. Staples owned nearby property around the year 1800. Also, the word may merely be a corruption of the word “stable” and in the colonial era, there were certainly many of those nearby.

On the brick building at #9 Jay Street at the NW corner of Staple Street you will see a terra cotta shield on the Staple Street sign bearing the initials NYH. Two buildings on either side of Staple Street at Jay Street were at one time associated with New York Hospital. The first, fronting on Hudson with its back facing the east side of Staple, was constructed in 1893 (Josiah Cady, arch.) as the New York Hospital’s House of Relief, or as we say today, emergency room. When the House of Relief was built, NYH was uptown, at 5th Avenue and 15th Street. The hospital had been established in 1771. After a merger in 1998 it became New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

The other NYH building is on the west side of Staple Street at #9 Jay Street. It was built in 1907 as a laundry building and stable serving the House of Relief on the opposite side. Somehow, a terra cotta shield cartouche bearing the initials N.Y.H. has survived, despite several building renovations over the years. It resembles similar shields found in older NYC subway stations, built in the same decade as this NYH annex, that carry the initial letter of the station stop.

That Confounded Bridge: Staple Street’s bridge is made of cast iron and has picture windows along the sides, and connects the third floors of the House of Relief with the laundry/stables. The Landmarks Designation Report states merely that it is a “later addition, designer undetermined” but it can be no older than 1907. I suppose I’m fascinated with it because while there are many older or more recent pedestrian footbridges connecting buildings around town, they’re usually high above the street, and this one spans one of NYC’s more obscure alleys. It’s Staple Street’s trademark — its hidden nature has saved it.

While both NYH buildings were converted to residential as early as the 1980s, the accessibility of the bridge is a mystery to me. Perhaps some residents have the key to the inevitably locked doors that go to the walkway — if you’re a resident or caretaker who has the key and can let me on, there’s a lunch in it for you.

Look at the way the sun plays off the brickwork at #9 Jay Street.

There are a few addresses on Staple Street. While #3 and #4 have been given new entrances and facades…

#1 Staple Street, on the north end at Harrison Street, has been left gloriously “native.” Indeed there are the remnants of a long-ago tenant with scraps of a painted sign. Not enough remains for me to make out what it said. I can make out “Campbell &”.

#18 Leonard Street between Hudson Street and West Broadway has a relatively new painted sign advertising it as The Juilliard Building. It was built in 1883 and at one time was occupied by H.B. Claflin & Company, the country’s largest wholesale dry-goods store; its retail store on West Broadway is long gone. The building was originally owned by Helen C. Juilliard, the wife of Augustus Juilliard, a millionaire made rich by his dry goods and banking businesses. Mrs. Juilliard was a philanthropist who was especially interested in the plight of poor and malnourished children. She helped fund the first Floating Hospital:

The Floating Hospital was a revolutionary concept in the late 1800s, turning the routine occurrence of quarantine barges into a health excursion that combined medical care, healthy eating, and entertainment into one experience. Aboard the Floating Hospital, patients and visitors enjoyed puppet shows, dancing, sing-a-longs, art classes, games, celebrity appearances and movies. They snacked and lunched as they spied breathtaking views of sea and city. No wonder it was nicknamed the Happiest Place on Earth. In the wake of the success of the first Floating Hospital, the first Helen C. Juilliard ship launched on May 4, 1899. [Granby Drummer]

The Juilliard School of Music in Lincoln Center was established in 1905 and was funded in large part by a bequest from Augustus Juilliard.

#21 Leonard Street began its existence in 1868 as a police precinct and prison and was designed by Nathaniel Bush, who designed most of NYC’s police precincts in the era. Since 1918 it has been a commercial building used by Standard Rice Co., the Ronald Paper Co., the Hailer Elevator Co. (for storage and assembly of elevators), and the Empire Elevator Corp. and is presently residential. No doubt none of its occupants know it was once a precinct.

Much more from the reliable Tom Miller, the Daytonian in Manhattan.

The smallest diner I have ever been in, and the smallest booths I have ever sat in, can be found in the Square Diner at Varick and Leonard Streets. The building is actually an uneven rhomboid, not a square. Though a diner has been on this plot since 1922, the diner building itself was built in 1947; still fairly venerable. I was glad to see it open after a closure during the Pandemic.

From New York Magazine:

As if it dropped into town right out of Central Casting, the Square Diner is a den of mid-century, blue-collar charm in the midst of 21st-century Tribeca. The chrome-age exterior, like a train car or a World’s Fair ride, is the first indication that the diner will have you stepping back in time. Inside, the restaurant takes on a bit of an Art Deco nautical theme, with polished wooden bead-board on the ceiling and porthole-like mirrors along the back wall, just below the row of celebrity headshots that all look like they date from the mid to late eighties.

For interior views and some more history, see this FNY page.

The second New York Life Insurance Building was constructed at #346 Broadway at #108 Leonard from 1894-1899; the first one was built in 1868 but when original architect Stephen Decatur Hatch was again contracted to extend it, he passed away and his replacements, McKim, Mead and White, decided to start from scratch and replace it. Unfortunately I couldn’t get a good angle to get a shot of its most prominent feature, its clock tower; indeed it’s known as the Clock Tower Building. It is bordered on the south by Catherine Lane, which has been hidden by an overhead shed for at least two decades.

Heading west on White Street from Broadway, I found one of Tribeca’s alleys, Franklin Place, in much better shape than I had previously.

Nudged between the cast iron and marble fronts on White Street is #49, a structure that serves to set off the rest of the block, and perhaps the rest of the district, Synagogue For The Arts.

Tribeca was a very different place in the 1960s, when William Berger designed the Civic Center Synagogue at 49 White St. For one thing, the architect could insert his unique, flame-shaped creation onto a block of 19th-century loft buildings without a thought to what the Landmarks Preservation Commission would say. Tribeca’s historic districts were still decades away.

The synagogue did not need space for a Hebrew school because there were few families in the area, just workers in the nearby warehouses and municipal offices who needed a place to pray during the day. And, of course, it was some 30 years before terrorism would happen here.

The building’s expansive plaza—above which the synagogue’s curved, white marble facade appears to float—seemed to offer the solution. [Wired New York]

You might be surprised to hear it from me, but there’s a place in the world for Modernist buildings and innovative design in a city that has become increasingly stolid and boring in its architecture the last couple of decades and I’m actually glad this was built before Landmarks Preservation could say NO. However: I wish the congregation would regualarly clean the exterior, since it seems to have accrued several years of crud.

Let There Be Neon, located at 38 White Street in Tribeca, has been making and restoring neon signs for 50 years. Owner and Brooklyn native Jeff Friedman has been with the company — which was founded in SoHo in 1972 by late artist, filmmaker and painter Rudi Stern — for 45 years. [NY1]

In 2006, FNY published a sampler of older neon signage around town…some of which have disappeared since.

At the triangle at the Grand Hotel formed by Church Street, White Street and 6th Avenue we find one of Manhattan’s newer street clocks, but my camera was focused on that painted ad saying “look for the clothespin tag.” That was once part of an ad for Marlboro Shirts, a brand popular in the 1940s.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

1/1/23

4 comments

Thanks you so much Mr Walsh. I truly appreciate your website and all the work you do, especially the pictures which bring back so many memories.

I know I sound like an old person, but…. I grew up in Maspeth, Queens, but left NYC in 1980. I am still very surprised and appalled that graffiti is still a ‘thing’ in this day and age. It’s so 1970s.

Two renamings that have stuck are the Jackie Robinson Parkway and the Marine Parkway-Gil Hodges Bridge (okay, not a full renaming). Maybe it’s best to rename things after athletes than politicians.

Ed Koch Bridge (Feelin Groovy) just doesn’t have the same ring

After 9/11 there was a pedestrian bridge over West Street at Vesey, next to Verizon headquarters.