By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

THERE are few parks in the city that are older than Central Park and rise near its level of fame. Battery Park is certainly known to all New Yorkers and international visitors as the dock for boats heading to Ellis and Liberty islands. This park has served as a public open space at least since the early 19th century. In the two centuries since then, it has undergone many changes, and some changes that were planned but never realized.

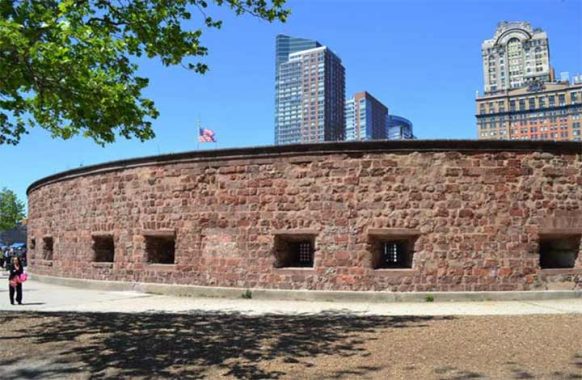

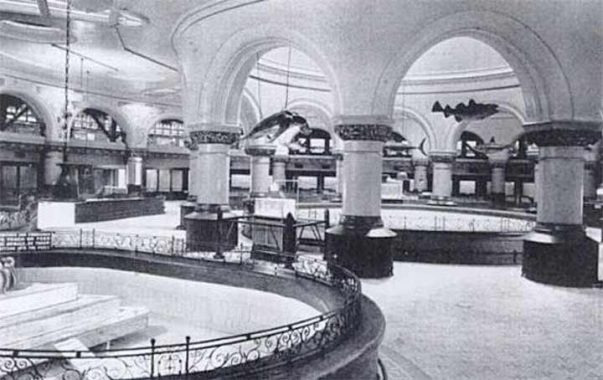

The oldest structure in the park is Castle Clinton, a National Monument enveloped by city parkland. Built on a pile of rocks that were enlarged as an artificial island, the rounded fort was built in 1807 to deter the British from returning. Having never fired a shot in war, the federal government handed the fort to the city in 1822. It then served as a concert hall, immigrant processing station, and then it hosted the New York Aquarium. The fish tanks left the fort in 1941 and a decade of uncertainty followed before the National Parks Service stepped in to preserve Castle Clinton.

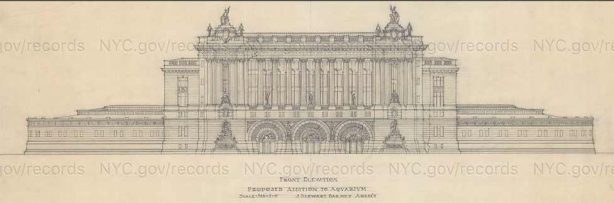

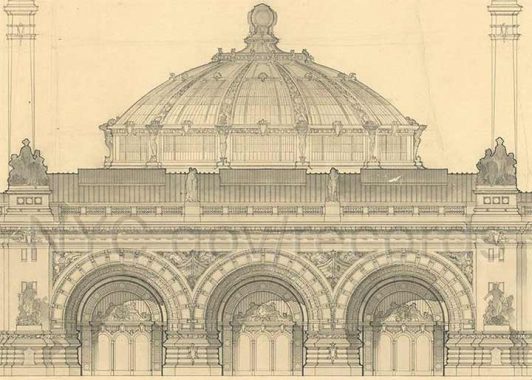

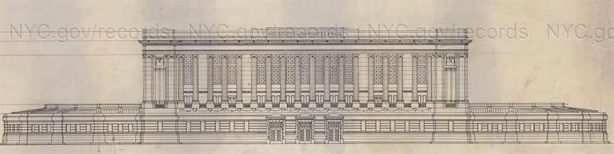

Between the aquarium’s opening in 1896 and its closing, there were proposals to knock down the fort in favor of an ambitious facility. A beaux arts design would have matched the Customs House across the street from Battery Park, being the preferred style at the turn of the 20th century. A search in the Municipal Archives reveals renderings for the unrealized aquarium.

By the 1930s the aquarium had two stories built atop Castle Clinton whose design transformed the fort into a castle. Designed by engineer Gustave Steinacher and the firm McKim, Dead & White, this addition matched the appearance of the historic fort.

The 1911 proposal by architect and painter John Stewart Barney envisioned a palatial venue for the aquatic creatures while preserving the circular shape of Castle Clinton.

A year later he submitted another design that reduced the height of the building in favor of a dome and glass canopies.

Barney’s third design proposal was a simplified classicist structure, lacking in friezes and archways. It looked more like the Butler Library at Columbia University than an aquarium.

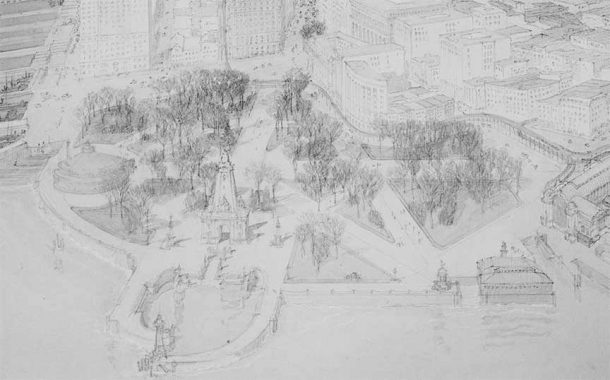

In the meantime the park’s landscaping also has a long history of unrealized designs. An untitled proposal from 1905 had the sight line of Broadway extended south into the park with a monument as its visual anchor. Likely it would have honored Commodore George Dewey, whose navy defeated Spain a couple of years earlier, resulting in the annexation of Puerto Rico, Guam, Philippines, and the base at Guantanamo Bay. The design included a small boat basin. The monument to this hero ended up delayed by decades resulting in a humble plaque placed in this park in 1973. In addition to this monument, the waterfront promenade nearby is named for Dewey.

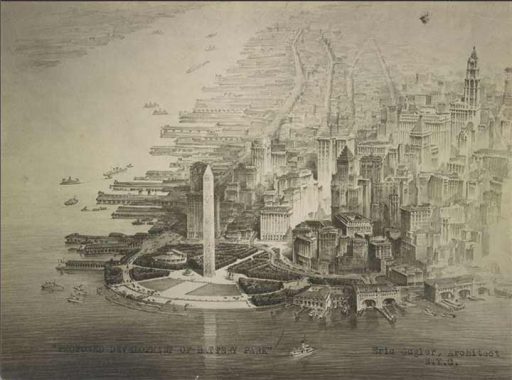

The southern extension of Broadway into the park was again proposed in 1929 by Eric Gugler with an obelisk memorial to World War One veterans facing a plaza on the waterfront. In that decade, dozens of parks across the city were named for individuals killed in “The Great War,” as it was known at the time.

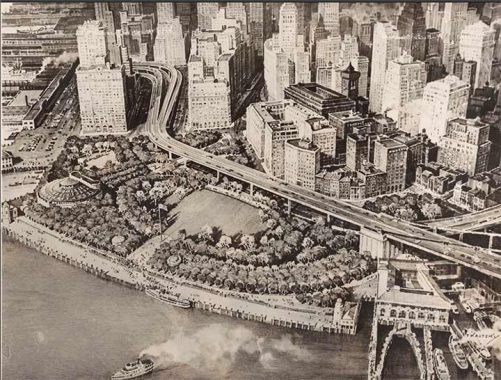

The appearance of Battery Park at the time was largely unchanged since the 1871 redesign, as seen in this Praeger aerial survey from 1934. The massive wave of immigrants who took the ferry from Ellis Island to the Battery tapered to a trickle following the restrictive quotas passed by Congress a decade earlier. The park hardly had any trees in it and one could imagine the noise from the elevated trains amplified by the lack of foliage. The trestle would be removed by the end of 1940, with the demolition of the Sixth and Ninth Avenue lines.

The trestle had yet to be removed when Robert Moses’ architect Gilmore Clarke proposed a redesign for the park in 1939 in tandem with the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge. The viaduct would have run on the edge of the park linking with the West Side Highway on its run uptown. Where Gugler had the obelisk, Clarke proposed a flagpole overlooking a lawn with views of the viaduct. Fearing that the bridge would be a wartime target, the federal government overruled Moses in favor of a tunnel to Brooklyn.

Clarke returned to his desk and drew the ventilation tower at Battery Place, but the obvious element in this 1940 plan is the demolition of Castle Clinton for a circular plaza that would have plaques commemorating the old fortress. A public movement to save Castle Clinton succeeded in shelving this redesign.

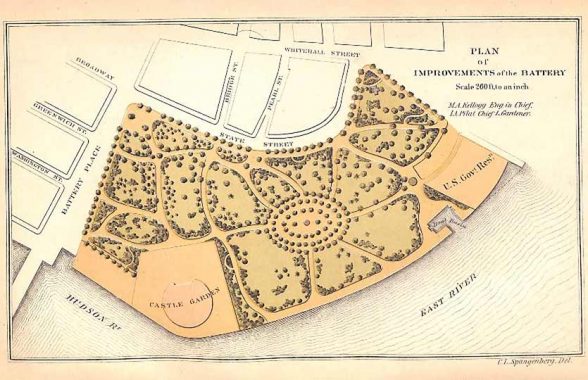

Going back to 1871 we see an Olmstedian layout for Battery Park by Ignatz Pilat that had winding paths and a circular grove. Castle Clinton was an immigration depot at the time, and excluded from the park’s layout.

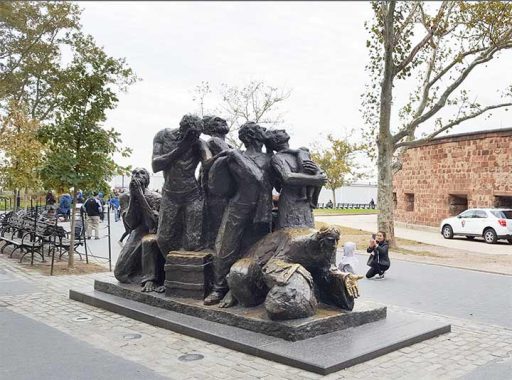

In honor of this role, Luis Sanguino’s sculpture The Immigrants, stands in front of Castle Clinton. It was sponsored by developer Samuel Rudin, whose parents came from Belarus in 1883 and initially settled on the Lower East Side. Their former synagogue later became a laundromat, as I’ve documented here.

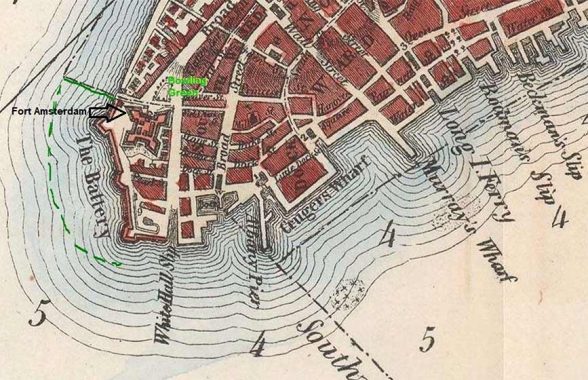

The oldest map showing Battery Park dates to 1807, showing an open green space shortly before Castle Clinton was built. At the time, Battery Place was an extension of Marketfield Street. The site of the Customs House hosted the Government House, built in 1790 shortly after New York lost its status as the nation’s capital city. It then became the governor’s mansion, but in 1797 Albany was designated as the state capital and the building lost its importance. It stood until 1815.

At that time, Russian diplomat Pavel Petrovich Svinin visited The Battery on his tour of the country and painted a watercolor of its flagpole with Fort Jay on Governors Island in the background. The painting and its description appear in his 1813 book Picturesque United States of America. He was an admirer of American democracy.

Going back in time to a decade before independence, this map from 1766 shows The Battery but no park yet. On the block where Government House would later stand was the city’s colonial citadel, Fort Amsterdam. It was built by the Dutch and later renamed by the British as Fort George, in honor of their king. The only park on the map that is older than Battery Park is Bowling Green, which deserves its own essay. After the Revolution, the embankment of the Battery was a popular place for a walk. During his brief time as president in New York, George Washington wrote in his journal about strolling on The Battery.

Most people who walk into Castle Clinton are there to purchase tickets for the ferry, but inside its wall there is a room with three architectural models of the park’s past. The first model shows Castle Clinton in its military role as an island connected by a footbridge to the park. State Street is lined with federal-style rowhouses, the desirable address of its time. The layout here is reminiscent of Charleston, whose downtown tip also has a battery park facing a harbor at the confluence of two rivers. The difference is that Manhattan’s downtown eventually grew with skyscrapers, while Charleston retains its low-rise antebellum residential charm.

The second model shows Battery Park after the elevated trains arrived in 1886. The site of Fort George and Government House had a set of rowhouses but behind them commercial buildings are rising up. Castle Clinton served as an immigration depot, the precursor to Ellis Island and JFK Airport. At the tip of the park next to the South Ferry dock is the Old Barge Office, whose tower overlooked the multiple ferries docking at this point: Staten Island, Governor’s Island, Atlantic Avenue, Red Hook, and Bay Ridge.

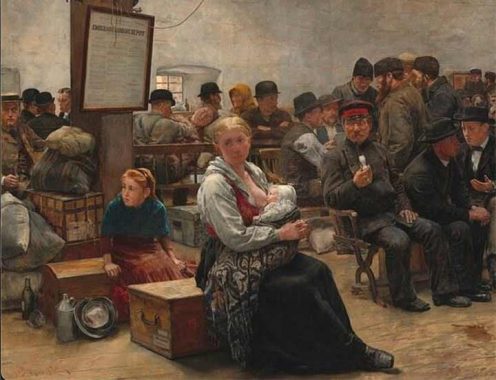

During its period as an opera house and immigration depot, the fort was known as Castle Garden. Artist Charles Friederic Ulrich depicted it in his 1884 work In the Land of Promise, which appeared in the World’s Fairs of 1889 and 1893, and now hangs at the National Gallery of Art. Where did this breastfeeding mother come from? She is sitting on a box with a label marked “Stockholm Central,” and she’s blond. I would guess that she’s from Sweden. At the time, the crowded conditions here made kesselgarten a slang in German and Yiddish for a noisy and chaotic scene.

The design of the Old Barge Office resembles Belvedere Castle in Central Park with the tower of the Jefferson Market Library in Greenwich Village. Daytonian in Manhattan has its detailed history, noting that this building was the second of three barge offices at this site. Behind this building are the elevated South Ferry terminal, the underground South Ferry station, and the ferry dock. Like Castle Clinton and Ellis Island, it had a role in welcoming immigrants to America. It was demolished in 1911 and replaced with a third version. That building stood until 1942, when it was removed by Robert Moses because it stood atop the route of the Battery Park Underpass. During the construction of the underpass, the granite foundation of the Old Barge Office was uncovered.

The site of the Old Barge Office is today a short segment of South Street that juts into the park. It has two addresses on it: the Coast Guard office and the Battery Gardens catering hall. Neither is architecturally significant, despite their highly visible location at the tip of Manhattan.

The final model shows Battery Park in 1941. In this scene, the elevated tracks are gone and the aboveground South Ferry Terminal remained in service until 1953 for the Third Avenue El. On Battery Place between the Whitehall Building at 17 Battery Place and the International Mercantile Marine Company at 1 Broadway is a block of low-rise buildings. They will be demolished for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and its ventilation shaft. The Whitehall Building was my family’s second stop in America after we arrived at the airport. In the 1990s it was the office of NYANA, a nonprofit that assisted refugees from the former USSR. From its windows we saw the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, where an earlier wave of immigrants had landed, coming from the same part of the world, for the same reasons as us.

The building with a tower next to Castle Clinton was a fireboat station that was demolished in that year as part of the Battery Park Underpass project. Dating to 1895, the ornate Victorian Engine 57 fireboat house provided permanent shoreside quarters for FDNY’s marine company. If anyone wishes to rebuild it elsewhere, the Municipal Archives has blueprints on file. The aquarium at Castle Clinton also closed that year in anticipation of its demolition. Although its upper floors were removed, the original portion of the fort survived as a result of a public outcry. The aquarium relocated to Coney Island, reopening on June 6, 1957.

Near the Battery Gardens where the Old Barge Office stood is a restroom from the 1940s flanked by two beacons. They appear to be the types used in a lighthouse. Without an explanatory sign, I could not determine where they were before being placed in this park. Behind them is the SeaGlass Carousel, a $16 million work of art that costs $5 for a ride.

The most recent redesign of Battery Park was in 1988 when the city approved a master plan for the park. The walkway connecting Broadway to Castle Clinton, situated on the path of the footbridge that connected to Castle Clinton’s island, was covered by an oval-shaped lawn. A winding bikeway was laid out on the park’s periphery, trees grow in a woodland section next to an urban farm, and most of the park’s monuments were lined up on Battery Place and State Street. Like Central Park, much of this park’s funding and maintenance is performed by The Battery Conservancy, a philanthropic organization.

Finally, in 2015 the park received an old-new name, The Battery, as it was known in the time of President Washington. But like the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel underneath it, most New Yorkers prefer a functional name and continue calling it Battery Park.

Learn More:

You can learn more about The Battery by visiting each of the hyperlinks posted in the essay above. Kevin has been to this park and its environs many times. Here are a few examples:

New South Ferry Station in 2009

Old South Ferry Station in 2008

Secrets of Battery Park

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

8/13/23

4 comments

One of the very best aquariums in the country is in the unlikely location of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

So I guess if my ancestors came during the Irish potato famine they came through

Castle Clinton,not Ellis Island and I bet it was way more chaotic during rush hour than

the relatively calm scene shown above.In fact,I bet it was a complete circus.

Robert Caro’s monumental Robert Moses biography, The Power Broker, devotes a whole chapter to the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge proposal. As originally designed the bridge would have been a double suspension bridge similar to the San Francisco – Oakland Bay Bridge that had opened in 1936.

It is absolutely true that opponents of Moses bridge proposal argued that it would be a target for enemy bombers in World War II, but it is more than that. The anti-bridge argument included the nearby Brooklyn Navy Yard, which would have been isolated and useless if the BB bridge were destroyed and left in shambles in the Upper Bay. Anti-bridge activists, who included Eleanor Roosevelt, also argued that the bridge would block the Manhattan skyline view from the Upper Bay.

It was one of the few times that Moses did not get his way, because the US War Department (today’s Defense Department) refused to allow the bridge to be built. Result was the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, which won out despite Moses’s argument that a tunnel would provide half of the bridge’s roadway capacity (8 lanes) and cost twice as much as a bridge. Tunnel construction began in 1940, and the following year Moses spitefully closed the Castle Clinton aquarium. World War II held up tunnel construction, which wasn’t completed until 1950.

My favorite football play – The Annexation of Puerto Rico,