IT was time to “call an audible” as they say in football, when the quarterback decides to change the play at scrimmage when the defense is lined up to defend perfectly the very play the coach and the QB had in mind. I decided to take a walk on the east end of Kissena Corridor Park, a green gash through Flushing and Fresh Meadows that defeats the overall street grid in spots. I found today’s photos (June 29, 2024) compelling enough to rush them out, especially since I have been ultra-urban of late, aiming the camera in commercial areas to snag new and interesting signage, I figured it’s time to give greenery a chance, though botany and trees aren’t my strong suit. Therefore, you’ll see a lot of green here though I’ll still talk about infrastructure.

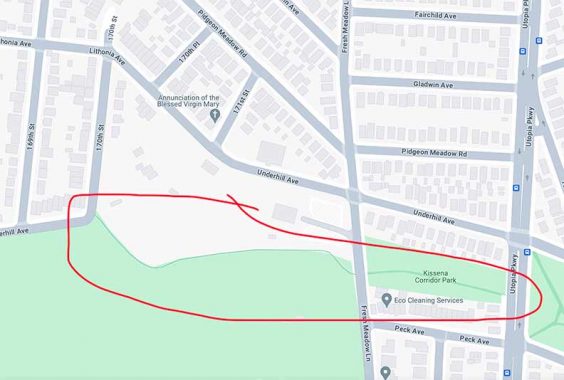

This Open Street Map excerpt shows roughly the portion of Kissena Corridor Park covered by me in today’s walk. In reality Kissena Corridor and Kissena Park itself are large and are comparable in size to, say, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. Kissena Park sits amid two lengthwise sections, known as Kissena Corridor. The western edge is at the Queens Botanical Garden at Main Street, with the east end of the Corridor at Francis Lewis Boulevard with the even larger Cunningham Park across the street. While sections of western and southern Queens are park-starved the same cannot be said about northeast Queens.

Kissena Park itself is quite large, a rhomboid formed by Kissena Boulevard, Rose Avenue, Oak Avenue, 164th Street and Booth Memorial Avenue. Its size is also augmented by the Kissena Park Golf Course, just east of the park itself. The park is divided into more “parkish” section on its north and a wilderness, a natural area that once included a bridle path on the south. That area is interrupted by the Kissena Park Velodrome, an oval bicycle track.

Why does Kissena Corridor Park cut across the street grid like this? The answer is that long ago… a very long time ago… before there were any streets at all… this was the route of a railroad. The Central Railroad of Long Island was built in 1873 by entrepreneur Alexander T. Stewart (1803-1876), the “merchant prince” who built NYC’s first department store on Broadway and Chambers Streets in 1848, to provide passenger service to Bethpage, Long Island from northern Queens to his newly-built village in Hempstead Plains, Garden City.

The CRRLI branched from the Flushing and Northside Railroad (now the LIRR Port Washington branch) at about where Citifield is now and ran generally east, with stops at Flushing Central Depot, currently Sanford Ave. and DeLong Street; Hillside, at Main Street (then called Jaggar Street); Kissena, at Jamaica Road (now Kissena Blvd.); Frankiston, at Black Stump Road (now 73rd Avenue), the Creedmoor Rifle Range stop at Range Street, crossed Jamaica Avenue on an elevated ramp and continued on into Nassau County. The line ran for only six years—until 1879, although a spur to Creedmoor hung on until 1955 when steam engines were retired from LIRR passenger service, and rails from the spur can, or could till recently, still be found on the grounds of Creedmoor State Hospital.

There are other abandoned railroads around town. Some have been converted into parks; however, the “user experience” at High Line Park on Manhattan’s lower west side and that of the Kissena Corridor couldn’t be more different, with the High Line devoted to art installations, adaptive reuse of the rail roadbed, and weird architecture on both sides of the elevated. (Nevertheless, I like it, and a recent walk I did there will make its way to Forgotten NY soon). The LIRR Rockaway Branch is currently in ruins, with various proposals on the table to restore rail service or make it a linear park (if that happens I suspect it will combine elements of the High Line and Kissena Corridor). The Staten Island North Shore Branch is in ruins, with no current plans for it. When the leaves are off the trees, I may do a dedicated survey of that line.

Meanwhile, the Bay Ridge LIRR branch, currently leased to the freight-only NY & Atlantic RR, and the Connecting Railroad in Glendale and Woodside, were slated to become a light-rail line, the Interboro Express. The line was supposed to get a good deal of funding from “congestion pricing” tolls, which were fiercely fought for by city-based transit groups and equally fought against by suburban, New Jersey and outer-borough motorists, who would have a surcharge applied to existing tolls and new tolls on East River and Hudson River bridges and tunnels. NYS Governor Kathy Hochul in 2024 put the initiative on hold; all new transit initiatives are also on hold. I question the wisdom of depending on the congestion toll for the majority of transit project funding. As Yogi Berra said, “it ain’t over till it’s over” and these projects aren’t dead, they’re in a coma for now.

When I’m in the Kissena Park area, I check on this building at 43rd Avenue and 159th Street. Why? The reason is simple. It was my first residence when I moved to Queens in March 1993 after 34+ years in Brooklyn (to be closer to a workplace in Port Washington). I have been in Queens since, and have been gradually shedding away my connections to Bay Ridge, as everyone I knew there has moved away or is deceased.

After a few months in a small apartment on the third floor, I moved to a larger one on the 4th floor. Its chief attraction was its eastern facing (the two windows top left), with the remaining windows facing the inner “courtyard.” I had just one air conditioner, in the bedroom (a practice I maintain today) and the sun shone directly into the living room. Thus I wrote Forgotten NY the Book there in 2005 sweating the entire time. When I arrived the rent for one bedroom was $580 and when I left in 2007, incremental increases had moved it only to $725.

Socially these were nose to the grindstone years. When in Brooklyn I had hosted and attended numerous gatherings, but the Flushing/Auburndale border was too far away for the Brooklyn people, few showed up here, and we usually met in “the city” instead. There was one serious relationship that could have led to marriage, but I chickened out.

As for the building itself, it likely dates to the 1920s. I found the construction nondescript except for the interesting exterior brickwork. The spacious front yard, I was told, was because of the presence of an underground stream. I had my eye on Westmoreland Gardens in Little Neck as early as the 1990s before moving in in 2007 and I have never regretted the decision. As far as Little Neck itself, it’s gone downhill but that’s a subject out of Forgotten NY’s purview.

A look north on 159th Street from 43rd Avenue. I always liked that when I stepped out of the house, I could see one of the antique scrolled fire alarm lamp masts (these were adapted from street lamps holding bare incandescent bulbs with “radial wave” reflector disks. There’s another one at 161st and 43rd.

This section of eastern Flushing looks better the closer to Kissena Park you get. Here’s a look at Laburnum Avenue, which is one of Flushing’s alphabet plant streets from a (Ash) to R (Rose). These theme streets are a legacy of the Robert Prince commercial plant nursery, established around 1735, that gradually expanded to 115 acres and was joined by competing commercial plant farms. They thrived until after the Civil War, after which Flushing became increasingly urban and the land was needed for housing. Unlike much of Queens, large parts of Queens kept names instead of having numbers applied and the Prince plant avenues are included.

Some of the plants in the list are named for plants more familiar to botanists, like Kalmia, Laburnum and Negundo. Laburnum, amusingly called the Golden Shower Tree or Golden Chain Tree, are native to southern Europe and feature yellow flowers in lengthy clusters. Continuing something of a tradition among Flushing plant avenues, Laburnum joins Holly and Kalmia in being toxic if consumed; Laburnum is the most poisonous of the bunch — and Laburnum are in the pea family and its seed pods resemble peas. Caterpillars like the plant just fine. (I can’t help but think “and Shirley” when hearing the plant name.)

In Flushing Laburnum Avenue is one of the lengthiest ‘plant’ avenues, extending from Colden Street all the way east to 164th Street.

Oak Avenue, named for a plant familiar to all, forms to north end of Kissena Park between 160th and 164th Streets. On this walk I didn’t enter Kissena Park proper. FNY has covered it previously, as it was my “home park” from 1993-2007; I think it deserves more comprehensive coverage, but I plan on revisiting it in November when the leaves start to fall and a greater amount of the park is visible.

A sampler of some of the varied and attractive architecture on 158th Street and Oak Avenue near the park. I believe the blocks between Laburnum and Oak Avenues are worthy of a look from the Historic Districts Council for their Six to Celebrate series. I think landmarking is not in the cards because there has been more recent, uglier construction during the last 30 years.

Doctors’ offices aren’t my happiest places to be. However I’ve begun to pay more attention to doctors’ signage that has been around for decades with no need to change it. This is also supported by a scrolled mast (see fire alarm lamp above for another example). My own GP is in an office building where signage like this won’t be found.

Why is 164th Street so wide from Kissena Park south to the Grand Central Parkway? In the late 19th and early 20th Century, a trolley line connected Flushing and Jamaica, running originally through the farms and fields of Fresh Meadows. Service on this line was ended in 1937. In short order, the tracks were pulled up, the weeds paved over, a center median added, and 164th Street became the fast and furious stretch we know it as today.

South of Grand Central Parkway the trolley line veered off 164th and rode on its own right of way to a terminal on Jamaica Avenue at about 160th Street. In the decades since, most of this trolley route has been either eliminated or hidden pretty well, but the four-lane width of 164th Street is a legacy of the route. There was one lane of traffic on the east side of the street, with the rest taken up by trolley tracks. For more information see Stephen Meyers’ book, Lost Trolleys of Queens and Long Island.

Here’s what 164th Street looked like in 1926.

There is an unusual grassy expanse on the south side of Underhill Avenue between 164th and 170th Streets. Today an eastern “tail” of Kissena Park north of the golf course, it formerly served as a trail leading to Kissena Park’s extensive bridle trail system. Until 2016, the Western Riding Club at Pidgeon Meadow Road and Auburndale Lane served the trail, but there are no nearby stables these days.

Some unusual signage has been broken out here in addition to the horse crossing sign. Seesaws ahead! Also a bicycle crossing. Strangely, though, I don’t see a “DEPT. OF TRANSPORTATION” identifier on them, except on the Share the Road sign on Underhill (which is frequented by bicyclists, see the trail shown below).

Underhill Avenue is actually one of the more unusual streets on the Queens map. It begins at 164th, runs east to 170th, then begins again at Lithonia and 171st and runs on the north side of Kissena Corridor up to the Long Island (Horace Harding) Expressway; but as this 1922 Hagstom shows, it was originally mapped to run on the north side of the Motor Parkway all the way to the Nassau County line. I don’t know if any of that section of Underhill was ever built, as the 1922 map more represented the dreams of developers than reality (take the “i” out of reality, after all, and you have “realty”).

One of NYC’s least-known bicycle trails connects Kissena Park and the Corridor north of the Kissena Park Golf Course, crossing Fresh Meadow Lane before ending at Utopia Parkway where bicyclists can transfer to Peck or Underhill Avenues. It is part of the NYC Greenway, a collection of paths that are continuous between Brooklyn and Queens. Thgey run both along rights of way, as here, and along streets.

The only stop sign in NYC I know of that controls bicycle traffic (or attempts to) is here at the Kissena Corridor Greenway path and Fresh Meadow Lane, once a major north-south Flushing artery since supplanted by Utopia Parkway.

Peck Avenue runs along the south side of Kissena Corridor Park in a continuous section. However, it’s one of Queens’m longest and most interrupted named streets, between Flushing and Queens Village. Peck Avenue is named in honor of longtime Flushing resident and property owner Isaac Peck (1824-1894). He owned a department store in College Point for many years. Members of the Peck family are buried in St. George Churchyard on Main Street in downtown Flushing.

I have an expanded section on Peck Avenue on this FNY page.

“Among all of us who sing, Ella was the best”. — Johnny Mathis

“I never knew how good our songs were until I heard Ella Fitzgerald sing them.”

–Ira Gershwin

Ella Fitzgerald performed for 58 years, won 13 Grammy Awards and sold in excess of 40 million records. “The First Lady of Song” was born in Newport News, VA, and was orphaned young in life. She was discovered in an amateur contest sponsored by Harlem’s famed Apollo Theatre in 1934 and was soon the featured vocalist in Chick Webb‘s band.

Though Fitzgerald attended school at Mount St. Vincent and later lived in Addisleigh Park, several miles to the south, I didn’t associate her with Flushing. NYC Parks explains the park naming thusly:

In 2020, as part of an NYC Parks initiative to expand the representation of African Americans honored in parks, this playground was named for jazz vocalist Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996). Born in Newport News, Virginia, Fitzgerald moved as a child to Westchester County with her mother and stepfather. After the death of her mother, she went to live with an aunt in Harlem where she skipped school and her grades suffered. The authorities placed her in the Colored Orphan Asylum, a Bronx orphanage, and later to a state reformatory school, The New York Training School for Girls.

The new Parks signs I considered boring, but at least a splash of color has been added.

Kissena Corridor Park has a large expanse of green, prosaically named Athletic Fields. However, on this Saturday afternoon in June, precious few athletes. I imagine there was a time, not too long ago, when there were a lot of kids in Little Leagues playing baseball here on a given weekend. Area residents: are they always empty like this?

When I moved to Flushing in 1993 and started bicycling around, I was amazed at how wide the streets were built in eastern Queens. 58th Avenue crosses Corridor Park and meets Peck Avenue and 192nd Street, all pretty wide. However, traffiuc is s sparse that no stoplights are necessary and traffic is controlled only by a pair of stop signs on Peck Avenue and one on 192nd, with 58th Avenue traffic getting the nod to proceed at all times.

Kissena Corridor Park just north of the Long Island Expressway.

The Kwang Ya/Heavenly Voice Presbyterian Church at Peck Avenue and 193rd, which looks like one of those suburban churches you find in New England after crossing a covered wooden bridge or two. No real information online about it, but it probably has a history that predates the Korean congregation.

I noticed a large grouping of motor homes on Peck Avenue and the LIE service road. The gathering may have had to do with the Korean Presbyterian church, or the Fresh Meadows Jewish Center and temple next door, which I didn’t photograph because of the interesting times we’re living in. Any guesses why there were so many motor homes here?

When the Long Island Expressway was expanded from Horace Harding/Nassau Boulevard in the 1950s, it ran at grade but the city still had to provide a safer way for pedestrians/bicyles to cross it; thus, this bridge was constructed which gets you to the easternmost section of Kissena Corridor Park and the “back door” of St. Francis Preparatory High School. The lampposts appear on many of the expressway/parkway pedestrian bridges and once held incandescent “teardrop” fixtures, now sodium Holophane buckets. I think they are attempts at streamlining the appearance of bishop crook lampposts.

This watermelon vendor under the bridge reminded me of…

I didn’t attend “The Prep” as its graduates call it ( I was at Cathedral Brooklyn), but I have known quite a number of people who have and it’s almost as if I attended it myself. Cathedral basketball teams played (OK, they lost) to St. Francis basketball and handball teams. (Cathedral didn’t have a football team but The Prep has a longstanding rivalry with Holy Cross.)

As it turns out, St. Francis Prep has a rather interesting infrastructional history. The school was established by two immigrant Irish Franciscan Brothers as St. Francis Academy at #300 Butler Street in what is now called Boerum Hill in Brooklyn in 1858. It didn’t become St. Francis Prep, a preparatory school for college, until 1935, at the same time the academy’s college division separated to become St. Francis College, which is my alma mater. The site is currently occupied by the School For International Studies at Baltic and Court Streets, a high school. St. Francis Prep and St. Francis College are no longer associated, but both school’s sports teams’ mascot is a terrier.

In 1974 the decision was made for The Prep to move again, to Fresh Meadows, into the building formerly occupied by Bishop Reilly High School and constructed in 1962 as one of just four coeducational Catholic high schools in the Diocese of Brooklyn (which includes Queens). (I’m told that at Reilly, boys and girls occupied separate classrooms.) St. Francis Prep purchased the building and absorbed Reilly’s enrollees, thus becoming coeducational itself, in the true sense. A number of Brooklyn Prepsters had their commutes from Brooklyn lengthened considerably, but toughed it out for their senior year. I know at least 4 Prep graduates, and only one of them drive.

Making no bones about its Roman Catholic affiliation, Stations of the Cross are arranged in sequence along Francis Lewis Boulevard. Fourteen scenes associated with Jesus Christ’s passion and death are depicted at each “station” at which faithful stop to pray. The practice was founded by the Franciscan religious order.

Cows subsist on mostly grass, but there aren’t many blades to be found at Holy Cow Playground, at Peck Avenue and 199th street. The park was renamed from Peck Playground in 1998 in honor of the favorite expression of longtime NY Yankee shortstop and TV play by play/commentator Phil Rizzuto. Like Ella Fitzgerald, The Scooter did not reside in Flushing, but rather in Richmond Hill and Glendale, which also have parks and street corners that honor him.

Over the years, I haven’t paid enough attention to park lighting. In some cases, the lamps are mounted on mastless octagonal poles, with the park lights mounted atop the shaft and pointing downward. In recent years, LED lamps have been installed in increasing frequency.

From the east end of Kissena Corridor Park, I edged into the Fresh Meadows housing complex, where there are a couple of things I wanted to check on. The central Queens neighborhood Fresh Meadows, known best for the eponymously-named extensive residential community centered at 188th Street and the Long Island Expressway that was constructed there between 1946 and 1949 by the New York Life Insurance company. Prior to the apartment complex, the area’s claim to fame was Fresh Meadows County Club and golf course that hosted the U.S. Open in 1932. The housing mix is 3-story apartment buildings in garden settings, with a couple of high-rise towers.

Fresh Meadows History has some vintage photos from the 1940s and 50s.

Fresh Meadows takes its name from its contrast to neighboring Flushing, whose name is a transliteration of the Dutch “Vlissingen” meaning “salt meadow valley.” Ponds and creeks running through the neighboring area to the southeast were likely “fresher” or free of salt, and so Fresh Meadows replaced the harsher-sounding older name for the region, Black Stump, which apparently referred to burned, blackened stumps that marked the edges of farms. Until about 2000, one of Queens’ last remaining farms, belonging to the Klein family, sold produce on a roadside stand at 73rd Avenue and 199th Street.

65th Crescent in Fresh Meadows has the last remaining set of 1960s vintage White street signs with blue type that were installed by the thousands in Queens. However, second pair on a nearby pole were replaced by a new pole and a new pair of signs replacingthe vintage signs. Apparently these were commissioned by the housing development, as the Department of Transportation would have installed regulation green and white.

I am of two minds. The vintage signs were mostly illegible; however, their loss leaves just the pair attached to the lamppost as the last remaining of Queens’ vintage white and blues.

I’m a fan of Fresh Meadows’ low-rise, e.g. two-story buildings. This is one of NYC’s largest garden apartment complexes, mixing tall towers and short buildings. (I’m partial to my own complex, Westmoreland Gardens in Little Neck, which this section of FM resembles).

I had not inspected this pair of signs at 64th Avenue where it meets the buildings addressed 189-02 and 189-04 for a number of years. They are an exact match for the metal and enamel street signs installed on NYC streets in the 1950s and phased out in the 1960s, and have likely been here for nearly 70 years.

Fresh Meadows’ street layout is so maze-like that the mythical founder of Athens, Theseus, would need the ball of thread he used to find his way out. However there is no Minotaur lurking within, I don’t think. So complicated is the Fresh Meadows layout that 188th Street intersects with 186th Lane, which is marked by new signage, no fewer than three times, and the grounds have Circles, Crescents and lanes that weirdly conform to the Queens street numbering system, but strangely subvert it, as if a virus had infected it.

The 188th Street traffic circle at 64th Avenue is named for Edgar G. Holmes, the first New Yorker (in NY State) killed in the Korean War on July 9th, 1950; he was 18 years old.

From here, the dead dog humidity was beginning to wear, so I continued west to Utopia Parkway for the Q31 to Bayside. On a Saturday, the 30 minute wait was double the 15 minute ride.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

6/30/24

11 comments

Mmmm…..an album cover with the behind in mind

Excellent posting about an area I have passed through countless times, mostly by car but sometimes by bus. Just one correction, please, to the portion about 164th Street’s very wide portion south of the LI Expressway. “Service on this line was ended in 1937”, referring to the old trolley route along 164th Street, is not quite accurate. Trolley service, a part of the New York and Queens County Railway network, ended that year, but bus route Q65 immediately replaced the trolley and still runs today, one of the heaviest Queens bus routes. Queens-Nassau Transit Lines and successor lines called Queens Transit and Queens Surface Corp. operated Q65 and other neighboring lines until 2006, when MTA Bus Company took over. Q65 has always been a big route with base headways of 10 minutes during midday weekdays, and 12 minutes on weekends. It also runs 24/7.

Just north of the Floral Park LIRR station there’s a long narrow parking lot running diagonal to the neighboring streets that’s built along the Creedmoor Spur’s right of way, On the north/east side of the parking lot there’s an old concrete storage silo that’s now used mainly as a base for cell towers, and right by it there are a couple of very short pieces of rail. As far as I know this is the only remaining rail from the Spur, with the possible exception of some inaccessible pieces on hospital grounds.

Peck and Underhill were both directors of the Central Railroad of Long Island. The streets on which their names were bestowed ran along either side of the railroad right-of-way.

Regarding Bishop Edmond J. Reilly Memorial High School, yes, it was co-ed, but in a very, very narrow sense. The west wing, running along Horace Harding, was for the girls only. The east wing, running along Francis Lewis Boulevard, was for the boys only. The girls school office, the boys school office and the central administration office were located in the front portion of the main floor in between the two wings. No students of either sex crossed the border there. Behind it was the auditorium. The only co-ed events that took place there were theatre club productions, which were never during the school day. Behind that was the gymnasium. There were NEVER any co-ed gym classes, however, students could mix when there were basketball games against other schools. The cafeteria was also sexually segregated until the boys senior year, when they were scheduled to eat lunch with one of the girls grades. Unfortunately, having eaten lunch with only boys for three years, our manners were something this side of barbarian, so the girls mostly stayed away. The second floor had a huge library that straddles No-Man’s-Land, where boys and girls could freely mix, but were required to be absolutely silent, under the stern visage of the nun who was the Head Librarian. We may have been able to leer and lust, but were totally mute. It was not exactly co-ed as most folks might assume it should have been!

Interesting. My thought, and NYC Parks, was that Peck Avenue was named for Isaac Peck, prominent property owner in Flushing but this makes more sense. Do you have their full names? Does Seyfried mention them?

In the 1800’s rail mania swept the nation, and Long Island was caught up in it. Flushing was a very important economic and social powerhouse and many lines were constructed in, and through it. It would have been normal for wealthy residents to have invested in them. It is likely that the Isaac Peck you mentioned is the same person whom I believe was a director of the Central Railroad of Long Island. Seyfried’s 1960’s “the Long Island Rail Road – a Comprehensive History” is a brilliant work, in seven parts, that goes into incredible detail. For each of the many lines that became the LIRR he tells how the corporations were created, how the properties were purchased and bult, down to the number of cubic yards that were removed to create a “cut” in one place and were then dumped somewhere else to create fill. He provides rosters of station names and rolling stock, but did not create an index. As a result, there is no easy way to find where people are named in the books. I gave it a quick glance and could not find this information, but will try take a deeper dive soon.

I enjoyed your posting Of “Water Mellon Man” (the album cover was, ah, interesting as well). Moving right along, as a jazz aficionado, I love all things Ella Fitzgerald. However, as my wife observed, since Louie Armstrong, who many times shared the stage with her, is buried not too far away from Kissena Park, it might have been more fitting to dedicate the playground to him & dedicate a Harlem playground to “The First Lady of Song”. It’s also great to see how well northeastern Queens has avoided the urban blight of so many other parts of NYC & urban America in general.

Kissena Park was close to where I lived as a child in Jamaica. One of my early memories in the 1950s were the pony rides there.

Having grown up in the late 50s to mid 70s in the area and spending a lot of time in Kissena Park fishing, ice skating in the winter and engaging in borderline illegal juvenile hijinks, I really enjoyed this post –

brought back many memories. As for the motor home mystery, I may have a solution. There are a few parts of Red Hook, mostly near the large athletic fields, where groups of motor homes park, some not

moving for literally years. I suspect that the NYPD permits them to essentially “squat” because they are located in somewhat out of the way places where parking spaces are not at a premium. Based upon the

location of the motor homes in your post adjacent to a park, my guess is that the NYPD has opted to give them a pass there as well.

You should realize two things: the vehicles you refer to as “motor homes” are correctly called “recreational vehicles” (RVs). RVs provide all the comforts & conveniences of regular homes including onboard bathrooms. However, because RVs are motor vehicles they’re not attached to public utilities like sewers. While on the road RV owners stay at RV parks which provide hook-ups for electric current & also provide owners with access to “black water” disposal. Black water is wastewater from sinks, showers, & toilets. Parking on the street provides owners with none of the above & “black water” is released without regard to public health& is a violation & a hazard. Blue states & sanctuary cities that permit or encourage this have no shame & show their contempt for average citizens. However, the “dedicated public servants” in charge are the first to rage against the internal combustion engine, especially that great workhorse the diesel engine which powers the tractor-trailer units and locomotives that deliver the necessities of our lives. Demand enforcement to preserve public health.

I live in the area, campers and 18 wheelers have been a plague near the golf course on booth and near that church. I think its just available parking and not enforcing laws?