I’m continuing my “Under the El” series, which recently visited 31st Street in Astoria, with a walk under Manhattan’s last remaining el, which continues on as far as Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. It is a northern extension of the 7th Avenue IRT and runs above three separate streets — but spends most of its time above Broadway, which is one of the longest routes in New York City and also New York State.

Time was, you couldn’t swing a dead cat without hitting an elevated train in Manhattan. There were four trunk lines, the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 9th Avenue Lines that originated, in the case of the 9th Avenue, as early as 1868. However, those weren’t the only four streets darkened by els. Below 14th Street, els ran on Pearl, Greenwich, Allen, Division Streets and the Bowery, and above 110th Street, the 9th Avenue El switched to 8th Avenue, and below 23rd Street, the 2nd Avenue El ran above 1st Avenue. There were two major points of exchange between the lines at South Ferry and Chatham Square. Did you know 42nd Street had an el? It was a spur line that ran to Grand Central Terminal from the 3rd Avenue El. Other such “spurs” connected the 3rd Avenue El to the then-existing 34th Street Ferry across the East River and also connected the 2nd/3rd Avenue Els to City Hall. And, while the 6th Avenue El ran west on West 53rd to meet the 9th Avenue, a spur track ran up 6th Avenue to the 58th Street station. A spur of the 2nd Avenue El ran across the Queensboro Bridge to Queensboro Plaza. The Brooklyn Bridge connected Manhattan and Brooklyn el lines, as well.

Beginning in the 1930s, Manhattan’s els vanished, owing to greater subway construction (The IND was built between 1925 and 1950), bus routes, and real estate developers who wanted more sky views. The last “pure” el, not connecting to a subway, ran up 3rd Avenue in Manhattan up to 1955 and wasn’t eliminated in the Bronx until 1973.

But that wasn’t the end of elevated trains in Manhattan.

Several stations on the IRT line are in the Original 28 subway stations opened on October 27, 1904, between 50th Street and 145th Street. But IRT engineers weren’t finished and were not stopping at 145th. The 19-aughts — and on into the 1930s — were an era of feverish, concentrated subway building that puts to shame the over 40 years it has taken between first shovels for the Second Avenue Subway and its expected imminent opening in December 2016.

The IRT expanded up Broadway, reaching Inwood in March 1906 and Riverdale by August 1908. North of Dyckman Street, because of Manhattan’s topography reaching an uptown valley, the line was placed on an elevated structure (as it had been for the 125th Street station in Manhattan Valley in 1904). This elevated line has survived and thrived and will likely run as long as there is a NYC subway system.

Oddly I had never walked under the el, and the three streets it runs over, till November 2016 when I obtained the pictures shown here.

The Dyckman Street station is among my favorites, because it emerges from a tunnel into the light, like Brooklyn’s Parkside Avenue station and the Hunters Point Avenue station in Queens. Unlike those two statins, though, the Dyckman Street platform is entirely outdoors.

Dyckman is a big name in upper Manhattan — bookkeeper Jan Dyckman arrived on these shores from Westphalia (then under Prussian control) in the late 17th Century, married into the Nagle family and gradually controlled much of upper Manhattan Island. His descendants were prominent US patriots — the British burned down the original Dyckman homestead at what became Broadway and 204th Street, and his great grandsons built the farmhouse that still stands today.

The tunnel is labeled with the chiseled sign “Fort George 1776 1905.” The first date refers to Fort George, originally Fort Clinton, which was built by US patriots at about where George Washington High School stands at Audubon Avenue and West 192nd Street. Though the British eventually captured the fort, Colonel William Baxter and his Bucks County Pennsylvania militia were able to hold off British general William Howe’s troops long enough for Washington’s troops to escape to New Jersey (much of the Revolutionary War in 1776 in the NYC area consisted of Washington escaping to fight again).

The second date, of course, refers to the date that the tunnel was completed.

One of a pair of tiled Dyckman Street station ID markers. These are of indeterminate age. I don’t know if they’re original to the station (1906) or came along later; they resemble IND tiled signs. Both signs were lovingly restored during station renovations; many of the tiles had chipped badly.

Station renovations, which took the better part of 4 years, are now about complete. The station got a set of new lamp stanchions that hark back to the designs that were part of BMT elevated lines when they were built in the teens and twenties; but at this late date, many people forget, or have never heard, about the three subway divisions, the Interborough Rapid Transit, Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit, and the Independent Lines, that were built by three separate entities. The three lines were unified in 1940 and have been run by the city and state ever since. Old divisions die hard, though: IRT cars are too narrow for BMT and IND platforms, and so there are no revenue service track connections between the IRT and the other two branches.

When the uptown el was renovated, the original railings and signboards were preserved (as they were on the Westechester Avenue/Southern Boulevard line, in many cases, in the Bronx). Unfortunately regulation black and white MTA Unimark subway signs rule; the cobalt blue and white originals disappeared over 30 years ago.

The rolling stock used on the #1 and #3 lines, the R-62, can almost be seen as rolling antiques. They made their debut in early 1984 and, at the time, they were the first new IRT subway cars placed in service since the R-36 “World’s Fair” cars used on the Flushing Line (which themselves would remain in service until 2003).

I do prefer the use of a large illuminated bullet on the front end. That way you can identify which train is pulling in when it is still way down the platform or about to enter the station. The MTA does not consider this a priority and the newer R-143, R-160 etc. cars simply have a small illuminated red circle with the number or letter within at the front of the car.

The interior and exterior of the Dyckman Street station, with its large arched picture windows. As far as I can tell this is the only station built into the side of a hill (I know what you’re saying about the 181st and 191st Street stations, but they are actually built under or within hills). The presence of orange jackets with glow in the dark tape means that 4 years after it began, reconstruction here is not quite finished.

Dyckman Street is probably the best-known of the four roads that intersect at the station named for it: Dyckman, Hillside Avenue, Nagle Avenue, and Fort George Hill, which is actually a northern extension of St. Nicholas Avenue.

Once emerging from the tunnel, the el travels on Nagle Avenue for a few blocks. The street was named for a colonial-era German settler, Jan Nagle or Nagel; the family intermarried with the Dyckmans.

I always emphasize infrastructure which is why I am fascinated with els — fascinating things can be found under them, like this first generation curved mast post at Nagle Avenue and Academy Street. When octagonal-shafted lightposts first appeared in 1950 most were of the curved-mast with bracket variety like this one. Later, most were supplanted by the straight-mast and cobra necks found today. Sometimes, though, you’ll find a curved-mast straggler — especially under an el, where old or unusual things can be seen. I was happy and surprised to make this discovery, a curved-mast I hadn’t previously known about.

Academy Street, named for a vanished school, is first alphabetically among NYC streets (Abingdon Square doesn’t count…it’s a square.)

At 206th Street, Nagle Avenue’s brief asssociation with the el ends, as 10th Avenue takes over its route. I always found 9th and 10th Avenue’s existence this far north in Manhattan rather disconcerting.

Until 1890 or so, all of Manhattan’s numbered avenues kept heir names north of 59th Street. However, that year the city decided to give them a historical or local flavor and rename 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th Central Park West, Columbus, Amsterdam and West End Avenues, respectively. Of all of the avenues, only 10th/Amsterdam is continuous from end to end, making it second only to Broadway in overall length on the island.

Broadway and 9th Avenue at the Harlem River

However, in Inwood, 9th and 10th Avenues take their places again, divorced from their other sections by several miles! For example Broadway intersects all Manhattan numbered avenues between 4th and 9th:

Avenue Broadway intersects at:

4th Avenue 14th Street

5th Avenue 24th Street

6th Avenue 34th Street

7th Avenue 44th Street

8th Avenue Central Park South/59th Street

9th Avenue north of 220th Street

10th Avenue 218th Street

There’s a lot of streets in between! Note that Broadway intersects 10th before it meets 9th because it is going northeast at that point. It actually takes the path of a colonial-era track once called Kingsbridge Road.

At 207th and 10th Avenue, it pained me to have to pass by the Famous Jimbo’s Hamburger Palace without going in. I had lunch here a few years ago and I’d say it’s one of Manhattan’s best kept secrets. I didn’t go in because I didn’t want to have to scuttle about with a camera on a full stomach.

West 207th is a busy two-way street that goes to the University Heights Bridge, one of a number of Harlem River bridges designed by bridge architect Alfred Pancoast Boller, who has a Bronx avenue named for him way up in Eastchester. More on the UHB here: it is actually the first Broadway Bridge (see below). On the other side of the bridge, West 207th Street becomes Fordham Road.

West 207th Street and Post Avenue. Note the John’s Fried Chicken awning on the corner — especially the spelling. You will be tested later.

Buildings on the west side of 10th Avenue north of West 207th. Autorama, a used car dealership, looks as if it’s located in a building that used to be a theater, given its rather fancy ornamentation, Corinthian-style pilasters, most notably.

The 207th Street Subway Yard is a repair facility for NYC subway cars in both the IND and IRT divisions — mostly cars used on the A and C lines. NYC Subway has over 2000 photos taken from the yard.

What’s unusual here is the presence of a railroad crossbuck indicating surface trackage behind the gate. There are likely others, but this is the first one I’ve seen in Manhattan.

I’ve never seen a stoplight mounted at the top of a lamppost shaft in NYC before. These lamps are relatively new, having been installed on 10th Avenue under the el sometime in the early 2000s, and this was considered a convenient place to mount the light by the DOT.

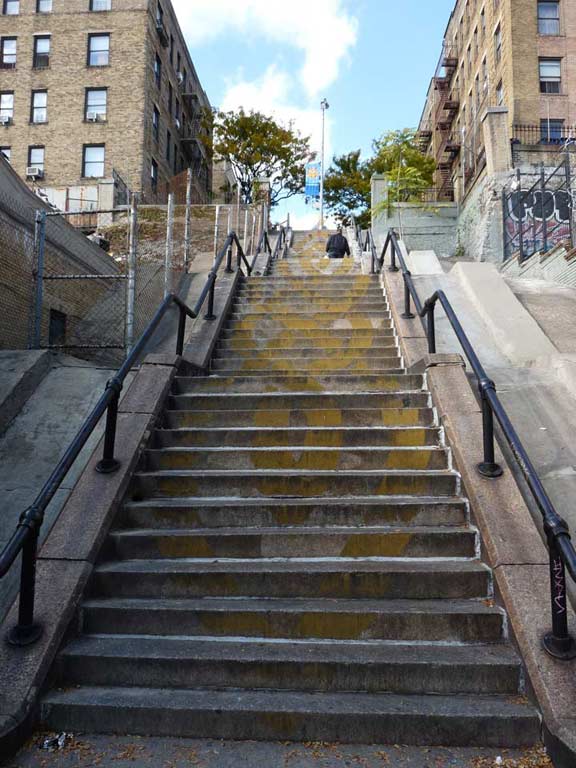

I detoured off 10th Avenue for a bit to get photos of a couple of my favorite local highlights. Uptown, some of the hills are quite steep, too steep for auto traffic in some spots, so the city built some “step streets” in the early 20th Century. There are quite a few in upper Manhattan, a lot of them in the Bronx, and relatively few in the three other boroughs. The 215th Street steps connect Broadway and Park Terrace East (which along with Park terrace West are named for Isham Park, pronounced “EYE-sham.”

The steps underwent a complete reconstruction just recently; part of the new additions are a rendering of how many steps are on each landing and how high an elevation there is to each landing.

I’m glad the city preserved this unique pair of lamps on the first landing on the Broadway side. There are lamps on the other landings that are short versions of Type B park lamps.

Here’s an Art Deco building entrance at 5057 Broadway that still has a stylized illuminated house number (that hasn’t worked in years.) It’s hardly the oldest building entrance in the neighborhood, though…

A large, Ozymandian stone arch can be made out behind an auto repair shop on the west side of Broadway at West 216th.

This is the last remnant of the Seaman estate. John and Valentine Seaman obtained 25 acres of land from Broadway to Spuyten Duyvil Creek and what would be West 214th-West 218th Streets in 1851 and set about building a hilltop mansion. The arch, meant as a gateway to the estate, was first built in 1855. Marble from quarries in the area was used in its construction. Evidence of a large gate, and even a room for a gatekeeper, are still in evidence at the back of the arch.

Between 1905 and 1938, the estate passed to Lawrence Drake, a Seaman nephew, and then to contractor Thomas Dwyer, who built several brick buildings on the site and razed the hilltop estate. Since then, it has served as a relic of the Seaman’s once grand domain (along with Seaman Avenue); sadly, it has been left to deteriorate. The original construction was so good, though, that it appears to be able to survive until someone actually tears it down.

Scouting NY has some photos taken over time to show how modernity crept into what used to be a country estate.

Since 1921, playing fields for the Columbia University sports teams have been located here at Manhattan Island’s northernmost tip. The land for the complex was purchased by financier George Baker for $700K and then gifted to the University; the complex has been named for Baker ever since. Lawrence A. Wien Stadium opened in 1984 and is the present home of Columbia’s football and lacrosse teams.

The playing field is named for Robert Kraft, a Columbia grad in 1963 and the owner of the New England Patriots, a team defeated in the NFL Super Bowl by the New York Giants on two occasions.

The former MTA logo is bricked into the side of the Kingsbridge Bus Depot at Broadway and West 218th. In my lifetime, the agency that runs the subways and buses, the Metropolitan Transit Authority, has had three different logos, the interlocking orange and blue TA when it was just the Transit Authority, the two-toned M used between about 1968 and 1995, and the “Doppler effect” MTA bullet used since then.

US Route 9 begins in southern Delaware, crosses into Cape May, NJ by ferry over Delaware Bay and then runs up eastern NJ, entering New York City (along with US 1) via the George Washington Bridge, and then follows Broadway and a number of extension roads nearly all the way to the Canadian border, paralleling Interstate 87 (the “Northway”) for much of the route, petering out as a service road next to I-87 just south of the Canadian border.

The present Broadway Bridge crossing the Harlem River has been in place since 1962, replacing an earlier swing bridge that carried the traffic and the elevated here from 1906 to 1961. Before that, the swing span designed by Alfred P. Boller carried cart and foot traffic over the bridge between 1895 and 1906 and has subsequently spanned the Harlem River at East 207th.

Even the Harlem River is partially man made at this location. Going back millennia, it was sleepy, shallow Spuyten Duyvil Creek, but it was straightened and dredged to allow ship traffic to use it. This left a meandering portion of creek surrounding the northern Manhattan neighborhood of Marble Hill, but by 1916, that was filled in, which left a small part of Manhattan politically a part of the borough, but now located on the mainland.

I have the entire story in detail on FNY’s Marble Hill page.

These are Metro-North Railroad tracks running parallel to the Harlem River; north of here, they will hug the Hudson. The Marble Hill station is on the other side of the bridge, west of Broadway. This stretch once belonged to the New York Central Railroad, formed from mergers of many different lines in the 1850s.

This is one of the few locations where an elevated train structure is a fully integrated part of a bridge infrastructure. (For example, at Roosevelt Avenue and Queens Boulevard, the existing el structures are simply stacked on top of bridges crossing the Flushing River and Sunnyside Yards, respectively.)

I’m probably forgetting other ones! Let me know at kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com.

Other examples from subway historian Andy Sparburg:

1) The Williamsburg Bridge probably qualifies as it was built to handle el trains from the beginning, although the trains did not begin running till nearly five years after the bridge opened (July 1908 vs. Dec. 1903 respectively).

(2) Possibly the F and G viaduct at Smith 9th Streets over the Gowanus Canal. The subway viaduct was built after the streets and vehicular bridge were built so this one may not qualify. But they both cross the canal at Smith and 9th.

(3) #6 IRT (Pelham Line) in The Bronx, where it crosses the Bronx River along with Westchester Avenue below, between the Whitlock Ave. and Elder Ave. stations.

We’re now on mainland USA, but not quite yet out of Manhattan — just in the neighborhood of Marble Hill.

I have often remarked about unusual infrastructural details found under els, and we have a few here on the Broadway el just north of the Harlem River, with more to come later on. The city has pretty much abandoned pendant lights suspended from elevated train structures elsewhere; there are a few stretches here and there on Roosevelt Avenue, West 6th Street in Coney Island, and here on Broadway.

Elsewhere, there is a stoplight stanchion normally used on telephone poles attached to the el structure, and a few of the pillars support J-shaped brackets carrying sodium yellow “bucket” lamps.

Meanwhile, another branch of John’s Fried Chicken, or rather, Jhon’s Fried Chiken, opened on this stretch of Broadway. I don’t know whether this is an error or a marketing gimmick!

Walking north on Broadway you pass the Marble Hill Houses (completed in 1952), and you are still “politically” in Manhattan. A careful look, though, at one of the walls of the housing project reveals a plaque, inscribed thus:

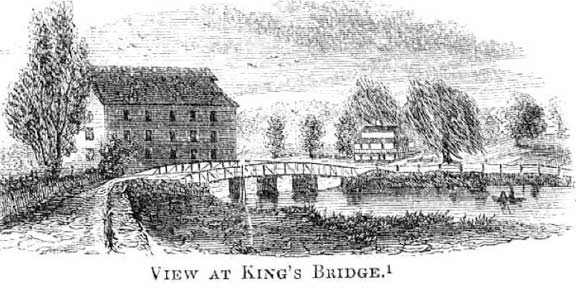

“Northwest of this tablet within a distance of 100 feet stood the original Kings Bridge and its successors from 1693 until 1913 when Spuyten Duyvil Creek was filled up.

“Over it marched the troops of both armies during the American Revolution and its possession controlled the land approach to New York City.

“General George Washington rested at Kings Bridge the night of June 26, 1776 while en route from Philadelphia to Cambridge to assume command of the Continental Army.

“This tablet was erected by the Empire State Society Sons of the American Revolution, June 27, 1914.”

Frederick Philipse built the first Kings Bridge, a tolled span over Spuyten Duyvil Creek, in 1693. Benjamin Palmer and Jacob Dyckman built a second bridge in 1759 to avoid paying the high tolls charged by Philipse. During his retreat from the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776, General George Washington used both the King’s Bridge and Palmer and Dyckman’s free bridge to escape to White Plains. The original Kings Bridge has inspired a network of roads in Manhattan and the Bronx, some surviving, some not, named for it. The span survived till the excavations for the Harlem Ship Canal between 1913 and 1916, though reportedly, the Bronx Historical Society maintains a small piece of it under Marble Hill Avenue between West 228th and West 230th Streets, in almost exactly its old position.

Frederick Philipse built the first Kings Bridge, a tolled span over Spuyten Duyvil Creek, in 1693. Benjamin Palmer and Jacob Dyckman built a second bridge in 1759 to avoid paying the high tolls charged by Philipse. During his retreat from the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776, General George Washington used both the King’s Bridge and Palmer and Dyckman’s free bridge to escape to White Plains. The original Kings Bridge has inspired a network of roads in Manhattan and the Bronx, some surviving, some not, named for it. The span survived till the excavations for the Harlem Ship Canal between 1913 and 1916, though reportedly, the Bronx Historical Society maintains a small piece of it under Marble Hill Avenue between West 228th and West 230th Streets, in almost exactly its old position.

We’re indeed in the Bronx after passing West 230th Street. I know I’ve repeatedly shown this classic Bishop Crook on the west side of Broadway between 230th and Kimberley Place, but this post is like church for me.

The shaft and mast look like a classic 24M Crook installed from the 1920s through the 1940s, but the base bears the lightbulb symbol of the Thomas Edison Company that was installed on the first Crooks from the 1910s, the smallish ones with the lamplighter crossbar, called the Type 1 BC. I suspect this is a hybrid post with the shaft and mast plopped on an older base.

Also note the Westinghouse AK-10 cuplight with the extended reflector bowl. Just a couple of these remain around town and they were always definitely in the minority. These were installed around 1950, give or take a few years.

I don’t know if it still works. The presence of a newer lamp next to it isn’t a good sign. Those lamps were originally post tops that a few years ago received the mini-cobra necks they still have today — though north of here, as I will show, some of the post top fixtures are still there in a few different types.

I have never eaten in Land & Sea at Broadway and Kimberley Place but I really like the vaguely Wrightian design in the front, and the porthole windows on the side, running up the side of a hill. Reviews are a mixed bag as usual.

There are a number of dead-end streets lining Broadway on the east side of the street between West 230th and West 238th. The reason for this is an abandoned railroad cut — the Putnam Branch of New York Central, which abandoned passenger traffic in 1958 and freight in 1980; it’s part of the John Muir nature trail along its stretch in Van Cortlandt Park, and, well, a rubble-strewn ditch south of the park, as NYC hardly ever converts old right-of-ways to urban trails. (If one neighbor protests, that’s enough to kill any conversion).

Verveelen Place is one of these dead ends and it is of particular interest, at least to Forgottenphiles, since it features a 1950-vintage single-curved mast post of the same vintage as the one on Nagle Avenue and Academy Street.

The short street does attract some traffic, as the parking garage for a nearby shopping mall was constructed there a few years ago, replacing a brick building that had a number of vintage “painted ads” on it that are now gone.

According to the late great Bronx historian John McNamara, Verveelen Place is named for ferryman Johannes Verveelen, who owned a nearby tavern in the late 17th Century. It was still in use during the Revolutionary War. Verveelen Place itself opened in 1922.

Passing West 231st, where there is an el station, you encounter the step street that leads up a high hill to Naples Terrace. Ultimately the street is named for real estate and insurance broker Edgar H. Napolis, whose development company was called Naples Holding Corporation. Napolis was actually from Naples, Italy and served in the Italian army from 1899 to 1904, according to McNamara.

A few Broadway posts have been fitted with new Light Emitting Diode lamps, which shine bright white. Supposedly they use less electricity and therefore, cost less to maintain. A variety of makes have appeared in NYC; these are by Cooper Industries.

Next week: up Broadway and into Van Cortlandt Park

12/10/16

1 comment

I grew up on Nagle near 204th St. and all of the photos shown were places I knew well and trod often. Thanks for the memories!