On a hot day in May I set out to visit most of Astoria’s historical spots and found most of them. I began at the LIRR station in Woodside and went north, west and south. My intention was to circle back to the Woodside LIRR but the humidity and a slight strain in my side from my camera bag turned me back a bit before I was able to do it. Still, I got 8 miles in — which feels more like 12 when it’s 88 degrees. Got to get acclimated to this, since it’ll be the rule till mid-September. I had hoped to make Astoria Park and perhaps Astoria Village (more of it seems to disappear every year) but those alone are worth a separate page.

Astoria…Ditmars Boulevard…the subway roll signs on the R train advertised these outlandish, far-off locales when I boarded it in Bay Ridge when I lived there for the better part of three decades, but I never really thought to trouble this northwest section of Queens, except for the occasional bicycle ride through, until I actually moved to Queens in 1993. Newcomers will find it extraordinarily hospitable, with Astoria Park, and its Olympic-size pool, facing Hell Gate and the landfilled island once known as Wards and Randalls Islands; a bustling Greek neighborhood centered along the main shopping drags, 30th Avenue and Broadway; spectacular views of midtown Manhattan and the Triborough and Hell Gate Bridges. In recent years, Astoria and its neighbor, Long Island City, have become increasingly welcoming to major museums as well; even the Museum of Modern Art set up shop in nearby Sunnyside from 2002 to 2004.

Astoria was named for a man who apparently never set foot in it. A bitter battle for naming the village was finally named by supporters and friends of John Jacob Astor (1763-1848). Astor, entrepreneur and real estate tycoon, had become the wealthiest man in America by 1840 with a net worth of over $40 million. (As it turns out, Astor did live in “Astoria”–his summer home, built on what is now East 87th Street near York Avenue–from which he could see the new Long Island Village named for him.)

Heading up 61st Street I noted the new American flag mural sponsored by the Woodside On The Move organization on the Long Island Rail Road overpass. Woodside is a travel hub that serves the #7 Flushing Line and every LIRR branch — the only station besides Penn Station to do so. The Port Washington branch cleaves from the main line a few blocks to its east. Also note the New Gumball lamp beneath the overpass. These yellow-burning sodium vapor lamps are gradually being grandfathered out in favor of new bright white LED lamps. The steps go to the eastbound Port Washington LIRR platform.

Churches are numerous in this corner of Woodside. According to the cornerstone the Korean Presbyterian Chucrh of Woodside, at 61st Street and 38th Avenue, was completed in 1986.

There’s an antiques dealer on 61st between 37th and 38th Avenues that has things like stone griffins and lions, but what really interests me is the radial wave lamp and scrolled mast in the driveway. These once lit NYC and Nassau County side streets by the thousands. Till recently the town of Roslyn in western Nassau still had a working flock of them, most of which have now been eliminated.

St. Mary, on 61st Street near 37th Avenue, is part of the Syro-Malankara Eastern Catholic Church which has its roots in the evangelic efforts of St. Thomas in the 1st Century AD, and interestingly has roots in both Syria and India. Portraits of Mary and St. George, the dragon slayer, flank the front entrance. This church building was originally dedicated in 1928 or 1938.

Playbill is a venerable institution in the theater community in New York and many other cities; its familiar yellow-and black-bannered magazine is distributed at all Broadway and some Off-Broadway plays, as well as at theater productions in many cities throughout the country. Its current circulation is in excess of four million annually. When distributed on the opening night of a Broadway play, the cover is stamped with a special seal and the date is printed on the title page of the magazine. Theatergoers as well as performers hold onto these keepsakes for years as proof that they were there on opening night for several productions that later went on to be blockbusters with thousands of performances.

Playbill, first printed in 1884, features articles on actors and new plays and musicals, surrounded by a wraparound section that contains listings and biographies of the cast, authors, playwrights and composers, lists of songs and who performs them for musicals, and setting and theater information regarding the play at which it is given out. The daily press run numbers over 80,000 issues.

Not many know that the Playbill printing press is in Woodside, on 61st Street just south of 37th Avenue!

A pre-1965 stoplight stanchion at 34th Avenue and 61st Street. How do I know? Easy. Before 1965 the bases were fluted as on this one. After 1965, the Department of Traffic (later Transportation) changed the bases to boxes.

The tall copper steeple of Christ Lutheran Church, on 58th Street north of Broadway, is a Woodside landmark, visible from blocks around as well as the LIRR Woodside platforms. The congregation goes back to 1896 and this building (which does not have a cornerstone date) may be the original. Services were originally conducted in English and German.

I hadn’t noticed these Woodside medallions before, though they were apparently installed in 2014.

The tracks carrying Amtrak trains to and from New England cross Northern Boulevard at 55th Street.

Commuter and intercity rail connecting NYC and New England has run over these tracks since the Hell Gate Bridge was constructed in 1916-1917. Here the line has just emerged from the Sunnyside Yards and the tunnel to Penn Station. It will soon join with the NY Connecting Railroad at 25th Avenue and cross the bridge across Randalls Island and into the Bronx. The supporting columns here were clad with concrete when it was built — but the concrete is now crumbling off.

The trestle is part of one of the most amazing transportation projects ever built: the tunneling of the Hudson River; the construction of the cavernous original Penn Station, bulldozed from 1963-1966; and the Hell Gate Bridge, completed in 1916, a relative golden age of railroading in NYC.

In the early 1920s a series of “White” themed fast food restaurants began to pop up all over the country. There was White Castle — still going strong and, in fact, the one at Northern and Bell Boulevards a few miles to the east is in one of the original locations. (I like the fare, but it tends to give your webmaster the repeats). There are the White Manna and White Mana hamburger shacks in Jersey City and Hackensack. In the early 2010, hamburgers are bigger then ever with Five Guys and Shake Shacks popping up like weeds all over the metropolitan area. Then, there was White Tower…

In the early 1920s a series of “White” themed fast food restaurants began to pop up all over the country. There was White Castle — still going strong and, in fact, the one at Northern and Bell Boulevards a few miles to the east is in one of the original locations. (I like the fare, but it tends to give your webmaster the repeats). There are the White Manna and White Mana hamburger shacks in Jersey City and Hackensack. In the early 2010, hamburgers are bigger then ever with Five Guys and Shake Shacks popping up like weeds all over the metropolitan area. Then, there was White Tower…

The Orange Hut at Broadway and 54th Street still carries the outlines and contours of its former life as a White Tower hamburger chain restaurant. The last White Tower closed in Toledo, OH in June 2008; the chain originated in 1926. There were about 230 White Towers at the chain’s height in the 1950s. The restaurants have operated in at least 14 states, including New York, Illinois, Michigan, Connecticut, New Jersey, Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida.

The interior of the Orange Hut still contains some hints of its origins, such as swivel stools adjoining a counter.

The attached houses along 53rd and 54th Streets north of Broadway are among the handsomest in Queens.

Many of NYC’s fire alarms have been hiding in plain sight since the 1910s, though many have been taken out of service because of false alarms, and also because 911 is three button pushes on mobile phones. The city does not paint them like this, but some neighborhood aficionados such as ex-firefighter Dave Herman, founder of the City Reliquary. I don’t think this alarm is his work, though. In a nifty touch, the FDNY initials are painted white.

It looks like an empty lot along 53rd Street north of 32nd Avenue, but it’s actually a cemetery that has been here for centuries. Queens was home to the Moore family, the family that gave rise to Clement Clarke Moore, to whom the famed poem A Visit From St. Nicholas is credited. Clement was the great-great-great grandson of Reverend John Moore, who became the first minister in the town of Middleburg (today’s Elmhurst) in 1656. Family descendant Nathaniel Moore, Jr. stipulated in his 1827 will that his real estate on either side of Bowery Bay Road (today’s 51st street) be sold after his death, with the exception of the family burial ground, located today on the west side of 54th Street between 31st and 32nd Avenues. Clement Clarke Moore’s permanent residence is in Manhattan’s Uptown Trinity Cemetery.

The cemetery was established by 1733 (the date of the earliest known burial) and has been known as the Moore-Jackson Cemetery since John Jackson married into the family and added to the cemetery’s acreage. He was, however, buried in the churchyard of St. James Episcopal Church on Broadway in Elmhurst. The last interment in this cemetery was in 1867.

Moore-Jackson Cemetery’s condition has waxed and waned over the centuries. By the 1910s, Nathaniel Moore’s dictum that it not be sold was holding firm, but the burial ground had become a weed-filled dump. It was periodically cleaned up, but always again fell into decrepitude. By the 1990s a more concerted effort was made and the cemetery’s condition has stabilized.

Augustine Moore’s well-preserved 1769 stone is right in the front, reading “AxM, dyed the 23rd Nov. 1769.”. “x” was occasionally used to separate initials in this era. Records show that he was the son of Samuel Moore, Jr, and died at age 17. Only a handful of the cemetery’s tombstones remain, however.

Never before has red been used for Department of Transportation street signs. New signs honoring local firefighters lost in the line of duty sport the color, with blue used for NYPD personnel in a similar vein.

Hiding in plain sight in NYC streets are ancient fire alarms, some of which go back to the 1910s. Newer, streamlined designs appeared in the 1950s but in many cases, these old stanchions were rewired to accept newer technology. The reason they have persevered is that they are controlled by the FDNY, not the DOT. While the city repaints some of them bright red periodically, some private citizens such as Dave Herman, an ex-firefighter who founded Brooklyn’s City Reliquary, give them additional trim like this; however, I doubt this is Herman’s work since it’s so far afield.

Boulevard Gardens, at the NE corner of 54th Street and 31st Avenue, was founded in 1935 as part of the United States’ New Deal initiative. T.H. Engelhardt designed Boulevard Gardens in 1933 in concert with renowned landscape architect C.N. Lowrie. Engelhardt and Lowrie brought the vision of the original developer, Cord Meyer Development Company to life. Currently, Boulevard Gardens is comprised of 963 residences with a mix of studios, one bedroom, two bedrooms and three bedrooms. Many of the high floor residences have Manhattan skyline views. The Gardens won an award for architectural merit from the Queens Chamber of Commerce.

At 31st Avenue, 54th Street also intersects Hobart Street, a small piece of the colonial-era Bowery Bay Road, which once ran continuously from Calvary Cemetery north to Bowery Bay, an inlet in the East River just west of LaGuardia Airport. The triangle formed by the three is now Strippoli Triangle, named for Pfc. Joseph Patrick Strippoli (1946-1968) a local soldier killed by a land mine near the Cambodian border with Vietnam.

PS 151, constructed in the 1910s, borders Hobart Street, once part of the ancient Bowery Bay Road.

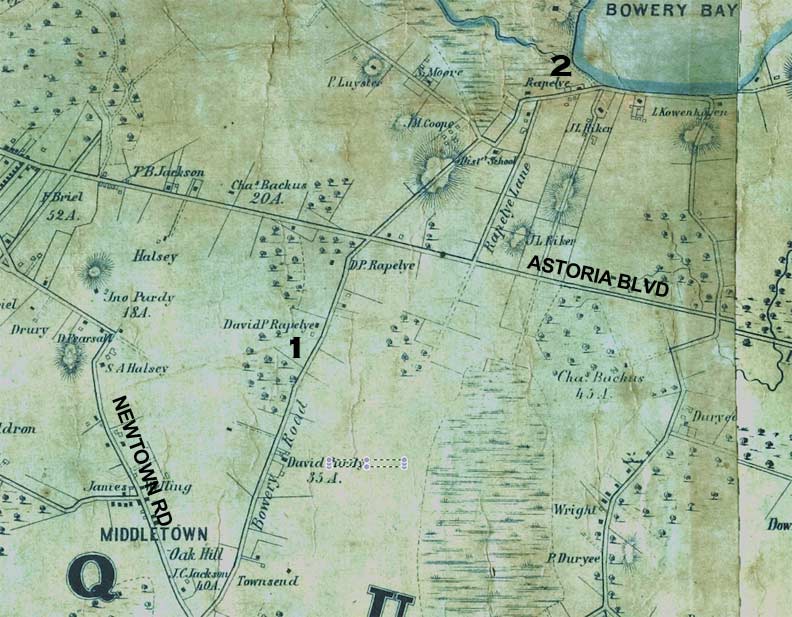

This 1852 map shows Bowery Bay Road from the former town of Middletown northeast to the bay for which it was originally named. I’ve helpfully marked the positions of the present-day Newtown Road and Astoria Boulevard. #1 marks the spot where PS 151 at 31st Avenue and Hobart Street is presently, while #2… I’ll get to that a bit later.

Though traffic is fairly moderate at Hobart Street and 30th Avenue, traffic flow is supervised by just a blinking red “cyclops” signal.

Railroads crisscross Astoria. The New York Connecting Railroad is a freight line connecting the Oak Point Yards in the Bronx with the Fresh Pond Yards in Queens, using the Hell Gate Bridge. Though more spectacular arches carry the railroad over streets west of here, on 49th Street there’s a more modest span here that also carries Amtrak.

Kitchen remodeling is done from this office, where spelling can be approximate.

49th Street between 25th and 28th (avenues are skipped) has a split look. South of the railroad, it’s lined on both sides with attached one or two-story residential buildings. Once you get past the trestle, you have cycle and scooter repair, as here, and other industrial businesses like elevator repair.

I went a block west on 48th Street between 25th Avenue and the BQE and found the same thing, but interspersed with some much older dwellings like this. They probably preceded all the industry in the region.

I am back on 49th Street between the BQE West and the Grand Central Parkway. In north Astoria, the Brooklyn Queens Expressway cleaves in two, with the western section going to the Triboro Bridge via the GCP, and the eastern section to LaGuardia Airport and beyond. Trucks and buses have to leave the BQE before the intersection, with large vehicles wishing to take the Triboro accessing it from the service road, Astoria Boulevard.

St. Michael’s Cemetery is a large cemetery (88 acres) accessible from 49th Street, here, and also from Astoria Boulevard south on the south GCP service road. St. Michael’s, named for an Episcopal congregation in Manhattan, is one of Queens’ larger cemeteries (though much smaller than Cypress Hills, Calvary or Evergreens) and lies north of Queens’ larger cemetery belts defined by Calvary/Mt.Olivet/Mt.Zion and Evergreens/Holy Trinity/Cypress Hills. It was established in 1852 and is the “permanent residence” of boxer Emile Griffith, inventor Granville Woods, “king of ragtime” Scott Joplin and mobsters Frank Costello and Joey Gallo.

![]()

Hard to believe it but I have not eaten here, Astoria Boulevard North and 70th Street at the classic Airline Diner, now a branch of the Jackson Hole burger chain, since September 2006, the same week the ForgottenBook came out, while being interviewed by ForgottenFan Jen Kitses for the Brooklyn Rail weekly. It occurs to me that I gave the Airline burger short shrift on my FNY Finer Diners page (most of the diners on it are gone now–I wrote it in 2001!). I take it back since the 2006 burger was first rate, in my opinion. The Airline has kept just about all of its old decor, including 1960s-style jukeboxes on every table, the ones with pushbutton controls and printed labels showing A and B-sides. Adam Kuban of Serious Eats (formerly A Hamburger Today) gave the Airline middling marks, but you’re here for the ambience as much as the meat.

The Airline is a Mountain View and has held down this locale on Astoria Blvd. since 1952. As you probably know, the diner along with Goodfellas/Clinton Diner, is in scenes of the Scorsese mob epic Goodfellas. East of here, Astoria boasts the Buccaneer Diner and the vanished Deerhead Diner.

Wait a minute. We’re on 70th Street? We were just on 49th! In north Astoria, the streets skip over twenty blocks because of a change in the street grid. Astoria’s streets are skewed SW to NE, while in the rest of Queens, they run more north to south. If you look at the map, the Sunnyside Yards form a barrier between the two grids, but here, they meet with Hazen Street serving as the divider. West of it you’re in the 40s, east of it, you’re in the 70s. South of here, Broadway serves as the changeover point between the grids.

Unique among the parkways and expressways conceived by longtime NYC traffic czar Robert Moses, the Grand Central Parkway has decorative “gateposts” on the east and westbound lanes opposite St. Michael’s Cemetery.

Donhauser Florist at Astoria Boulevard North and 72nd Street has been part of the Astoria scene since German immigrant Hans Donhauser established the business, serving funerals at St. Michael’s Cemetery, in 1887. His great-granddaughter Gladys still ran the business as of 2014. photo courtesy Greater Astoria Historical Society

I was drawn to this house on Hazen Street at 74th, surrounded by pine trees, a ranch-style wood fence, and other trees that were emitting small brown spores that had covered the ground and the cars (what kind of trees are those?

The bridge to Rikers Island connects Hazen Street and 19th Avenue with the island; the Q100 bus brings visitors to the island, which the mayor and several other politicians want to close, citing inferior conditions (and likely the real estate $$ it would command if it were developed for other purposes).

19th Road is a short street running between 77th Street and 19th Avenue on the eastern edge of Astoria, wedged between the Grand Central Parkway and La Guardia Airport. But, if you check the 1852 Queens map shown previously on this page, it is a remnant of Bowery Bay Road and once skirted the edge of that very bay. Why has it been preserved?

![]()

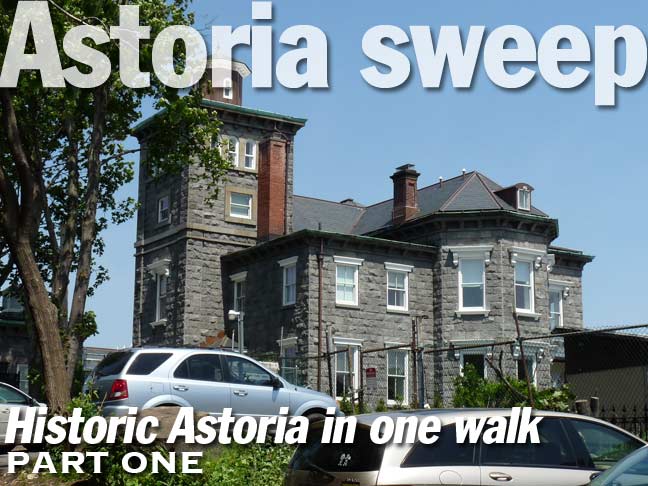

Lent-Riker-Smith House, today and in 1900 (it’s better seen in winter, left). This is a colonial farmhouse that was by most accounts built by Abraham Rycken Van Lent in 1729, though some historians date the oldest part of the house to be even older…perhaps 1656, according to an American Historic Buildings Survey (HABS is a branch of the Library of Congress). The Lent-Riker-Smith Homestead’s website hews to the 1650s date, and if any of the house is that old, it would beat out Flushing’s Bowne House by a couple of years. Rycken, whose family later changed its name to Riker, is remembered by most New Yorkers for the offshore island he acquired from New York governor Peter Stuyvesant in 1664, later acquired by NYC’s Department of Corrections in 1884. Riker would no doubt have preferred that his well-preserved Queens home be his chief remembrance.

Lent-Riker-Smith House, today and in 1900 (it’s better seen in winter, left). This is a colonial farmhouse that was by most accounts built by Abraham Rycken Van Lent in 1729, though some historians date the oldest part of the house to be even older…perhaps 1656, according to an American Historic Buildings Survey (HABS is a branch of the Library of Congress). The Lent-Riker-Smith Homestead’s website hews to the 1650s date, and if any of the house is that old, it would beat out Flushing’s Bowne House by a couple of years. Rycken, whose family later changed its name to Riker, is remembered by most New Yorkers for the offshore island he acquired from New York governor Peter Stuyvesant in 1664, later acquired by NYC’s Department of Corrections in 1884. Riker would no doubt have preferred that his well-preserved Queens home be his chief remembrance.

Since the 1970s, the Lent-Riker Homestead has been owned by Michael and Marion Duckworth Smith, who have added a garden complete with columbine, magnolia, foxglove and tulips, along with a decorative gazebo and “gingerbread house.” The Smiths have completely refurbished the house to perhaps as grand a condition in which it has ever been. Michael Smith, a media executive, passed away in 2010 and is interred in the Riker family cemetery, which adjoins the house. Mr. Smith, who had an office in the Quinn Building that is also Greater Astoria Historical Society HQ, was often a cheerful presence while I was there. His widow, Marion, periodically opens the house for public tours.

The cemetery contains some of Queens’ oldest gravesites, including patriarch Abraham Riker (1746); and his son, also named Abraham, who died at Valley Forge (1778); several Irish patriots are also interred here.

For a definitive stroll through Bowery Bay and northeastern Astoria, Sergey Kadinsky has you covered in this FNY page.

Carlos Lillo Park, in the triangular intersection formed by 20th and 21st Avenues and 76th Street, is relatively new (2008) and was named for an area paramedic who lost his life on 9/11/01.

I’m drawn to ranch houses, mainly because I have always despised climbing staircases. When I worked for the well-known direct marketer in Port Washington, it was located in a one-story building– really, a vast ranch office. The company has since moved to Jericho but I believe the old building deserves landmark status, or whatever they do to preserve buildings in Nassau County. 21st Avenue and 49th Street and can be seen better here.

This new house is nearby. While I don’t like basement garages much, cars are necessary in this transit-starved enclave and I do like the brick exterior and the almost Queen Anne-esque unevenness.

The Roman Catholic St. Francis of Assisi Church, 21st Avenue and 45th Street, remains in the handsome Tudor structure that was its first church building, constructed in 1931; for about a year services had been held in Continental Hall on Steinway Street.

St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226) has been called the most beloved Catholic saint, and representations of him are certainly the most recognizable (other than, perhaps, St. Sebastian with the arrows). His story as a preacher, mystic and founder of the Franciscan Order would make a terrific Hollywood movie (but who would make it? Mel Gibson?)

Francis is known as the patron saint of animals and is often depicted with them. The story goes that while traveling with friends he happened upon an unusual number of birds in the trees along the road. He excused himself and said to the birds: “My sister birds, you owe much to God, and you must always and in everyplace give praise to Him; for He has given you freedom to wing through the sky and He has clothed you…you neither sow nor reap, and God feeds you and gives you rivers and fountains for your thirst, and mountains and valleys for shelter…” wikipedia

![]()

The Steinway family, master piano builders, transit magnates, and resort developers, put a personal stamp on the neighborhoods in which they resided that is visible even today. Henry Steinweg, a German piano manufacturer, immigrated to New York City from Seesen, Germany, in 1853. His sons Henry Jr. and Theodore set about making the finest pianos ever made, renowned the world over.

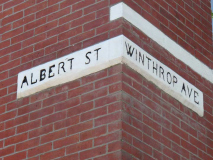

Henry Jr.’s and Theodore’s younger brother, William, continued the family tradition (advertising their instruments as “the standard piano of the world”) and moved the operations of Steinway Pianos to Astoria, Queens. Between 1870 and 1873, William Steinway purchased 400 acres of land in northern Astoria and not only built the spacious Steinway piano factory, which still cuts an imposing figure, but a small town with a library, a church, a kindergarten, housing for factory workers, and a public trolley line. From 1877 and 1879, Steinway constructed a group of handsome row houses on Winthrop Avenue (today’s 20th Avenue) and on Albert and Theodore (41st and 42nd) Streets. Even the street names bore witness to the Steinway family, since Albert and Theodore were sons of Henry Steinway. These homes were rented by the Steinways to their workers. The area is collectively known today as Steinway Village. A detailed map exists of the old village, but it must be viewed in person by anyone who has a copy because of its incredible detail.

William Steinway’s mansion, on 41st Street, still stands on a high hill that has never been leveled, unlike the surrounding area. 41st still looks like a country lane.

Unexpected remnants of Steinway Village, as well as obvious ones, can still be found in the area. On either side of 42nd Street and 20th Road (itself a northwestern tributary of the old Bowery Bay Road) we find a large building that formerly held Thielbahr’s Grocery, which served area Steinway workers, and on the other side of the street, several buildings once home to managers at the piano factory. A few of the original architectural elements of each still shine through the modern aluminum siding.

These attached houses, constructed by the Steinway company in the 1870s along Theodore (41st) Street and Winthrop (20th) Avenue were once leased to regular workers at the Steinway factory and are all privately owned today. They are airy, liberally lit with sun, and have green spaces in the back. The homeowners of today, however, have resisted efforts to place the neighborhood under the aegis of the Landmarks Preservation Commission because they feared that designation would prevent them from making any alterations.

Steinway Mansion looms looking north on 41st Street

Next week: Steinway Mansion and the heart of Astoria

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

5/27/18

6 comments

The St. Francis of Assisi movie has already been done, almost 60 years ago (1961), with Bradford Dillman as St. Francis and Dolores Hart (now a nun) as St. Clare.

Also Zeffirelli’s “Brother Sun, Sister Moon” from 1972.

Missing from the story is a very important part of street lighting history in New York City. The Street Lighting Equipment Company was located at 31-23 61st Street. They were one of the suppliers to the Department of Water Supply, Gas And Electricity. They are long gone, but their traces can still be seen on the building, and on 61st street. I walked by there several weeks ago and the building still has the two NYC floodlights with their 1960’s era photoelectric controls, mounted to illuminate the front of the building, Also, on 61st street, there are two remaining 25 foot fabricated steel poles equipped with type10 (“Deskey”) aluminum arms. Before NYC began a general replacement of mercury vapor lighting, if a community group, or a business district,or an individual company desired to brighten their street with High Pressure Sodium lighting, the City would pay for the installation so long as the fixtures and lamps were donated. The Street Lighting Equipment Company donated the fixtures for the three poles on 61st Street. Because of a severe steel shortage in the early 1970’s,the City was forced to adapt Deskey arms to the existing steel poles. ( I remember the City Agency I worked for could not get 2” galvanized steel rigid conduit as late as 1974)

In 1976, SLECO was involved in a lawsuit against the City. A law had been passed that even if a bid from a firm in NYC was 10 per cent higher than out of town suppliers, the City firm was to be awarded the contract. The City had advertised a bid for 3,000 type 10 (Deskey) poles. Garlet Mfg. Co. of PA. came in with a bid of $484,000, Sentry Electric Co. Long Island, $495,280, and SLECO $521,110. It was up to the Board Of Estimate to determine who won.

Those LIRR steps remind me of the long-closed LIRR steps at Gravesend Neck Road and East 16th Street in Brooklyn.

https://www.google.com/maps/place/East+16th+Street+%26+Gravesend+Neck+Rd,+Brooklyn,+NY+11229/@40.5950271,-73.9547607,3a,75y,316.01h,81.54t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sCiY5q9zq1d38DWOXdnc_yw!2e0!7i13312!8i6656!4m5!3m4!1s0x89c2448a340a9a47:0x861e90fa54028bd1!8m2!3d40.595013!4d-73.9547406

I live in the Ditmars part of “Ditmars Steinway” around the corner from this old home: https://www.google.com/maps/@40.782705,-73.9185694,3a,75y,12.13h,92.13t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1se293HH_xXCZdX-2uOOCocA!2e0!7i16384!8i8192

I have been fascinated by it. The NYPL and oldnyc.org have photos and records of it that date it back to the 1850’s, I believe. From Shore Blvd, it is very prominent. It is the last standing mansion north of Hoyt Avenue / Astoria Park South. Believe it or not, pictures from 100 years ago show it in ruin, yet somehow it survived and now seems to be subdivided into apartments.

There is one other smaller relic of a different time that you can find here: https://www.google.com/maps/@40.7766966,-73.9230302,3a,75y,178.21h,84.31t/data=!3m5!1e1!3m3!1setIyFn0UJK0KcbcQSfW-kg!2e0!6s%2F%2Fgeo0.ggpht.com%2Fcbk%3Fpanoid%3DetIyFn0UJK0KcbcQSfW-kg%26output%3Dthumbnail%26cb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile.gps%26thumb%3D2%26w%3D203%26h%3D100%26yaw%3D305.0593%26pitch%3D0%26thumbfov%3D100

Love your site, thanks as always and congrats on 20 years!

Those old homes on the south side of the GCP have always been a mystery to me. Moses must have ripped thru this area and a few owners said no. The houses had their basements lowered to meet the new street level. Maybe the homes are part of old East Astoria?