By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten New York correspondent

NEW YORK is a city of numerous fortresses that never experienced a battle. Following the British occupation during the American Revolution, the city fortified its outskirts and coastal approaches with blockhouses and forts to keep out the British and other imperialist powers. For the forts that are gone, there are neighborhoods and parks whose names honor their locations. In the case of Blockhouse Number Two in Morningside Park, the design of an elementary school hints at the history of the site.

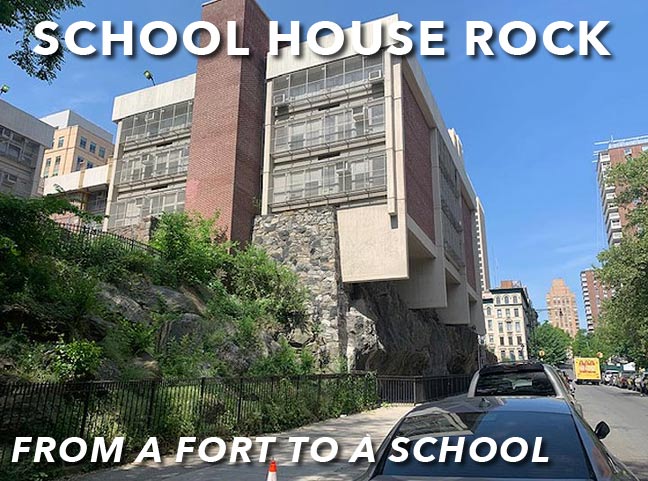

P.S. 36 – Margaret Douglass School stands atop an outcropping at the northern tip of the park, a Brutalist structure completed in 1966 on parkland that was designated for the school two years earlier. Like the proposed Columbia University gymnasium at the southern side of the park, this rezoning was also opposed by local civic groups. But it did not result in student-led sit-ins and rioting as was the case with the unbuilt gymnasium. At the time, Manhattan Borough President Edward Dudley called the 1.35-acre site a “rubbish-strewn and a danger spot for children.” The firm Frederic Frost Jr. & Associates looked at the Manhattan Schist, applying its color and texture to this concrete and brick building. On its northern side, the school is cantilevered atop the rock, exposing it on the sidewalk level.

Like a typical fort, the school has a courtyard on its northern side whose entrance resembles a defensive wall. This yard is used for deliveries and faculty parking. Another yard on top of this wall is used for recess. Similar to how the northern tip of Morningside Park was de-mapped in favor of a school, 20 blocks to the north, the tip of St. Nicholas Park was also demapped to give CCNY its library, which later was replaced with the engineering school.

On the south side of the school at Morningside Drive, the rock is less visible. I am not sure about the namesake of this school. It could be Margaret Crittendon Douglass, a heroic southern White woman who defended herself in a criminal trial on the charge of teaching Black children to read. After serving her one-month sentence in 1854, she moved to Philadelphia and disappeared into history. As we are on the edge of Harlem, it is certain that the namesake relates to Black history.

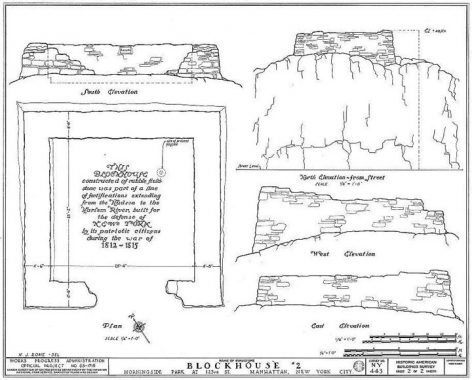

If one wishes to reconstruct the blockhouse, its twin in Central Park can serve as a nearly identical model. Also, during the Works Progress Administration of the 1930s, the federal government conducted the Historic American Buildings Survey with detailed plans of Blockhouse Number Two. Currently, there are no plaques or signs on this corner to commemorate the blockhouse or explain Mrs. Douglass. That’s why there is Forgotten-NY.

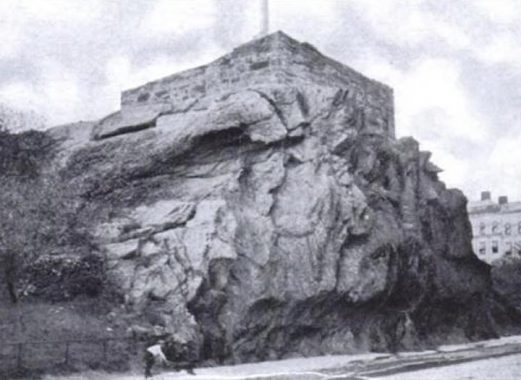

Before people had smartphones, before disposable cameras, before all of that, postcards were widely circulated with depictions of neighborhood sites. An undated one showing the blockhouse has the outcropping and apartments in the background that are still there today.

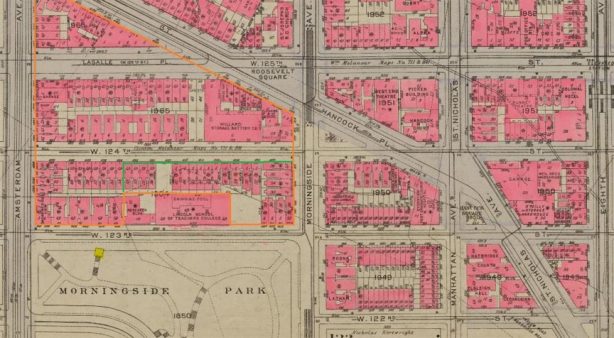

On the 1930 Bromley atlas, we see the blockhouse sticking out the park and one can imagine the views north across the Manhattanville Valley. The blocks within the orange lines would be condemned in the 1950s in favor of public housing. This complex of nine towers is named after Ulysses S. Grant, the Civil War general and 18th president whose tomb is a couple of blocks to the west. In 2008, Morningside Park was designated as a Scenic Landmark, precluding any further development of this Olmstedian green space.

A portion of the Grant Houses superblock was developed as Playground 125, named after the nearby cross street and Public School 125. It is a typical 1950s schoolyard-park in contrast to the greenery of Morningside Park across the street. The school is co-named in honor of Ralph Bunche (1904-1971), a grandson of a slave who became an educator, diplomat, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. As the city continues to rename parks and streets in honor of individuals who challenged stereotypes, fought for equal rights, and defined their neighborhoods, I have no doubt that at some point the functionally named Playground 125 will have a human namesake.

On our “tour of duty” across the city, Kevin and I have documented numerous forts, such as Fort Hill, Fort George, Fort Totten, Fort Stevens, Fort Tilden, and many more. This one is perhaps the smallest fort so far.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

6/25/21

4 comments

Another fascinating story! Thanks for sharing that with us.

I find it interesting how placing that school was approved seeing that it was placed in a park where it normally wouldn’t go.

Since then, a state law on parkland alienation requires that any parkland lost must be made up nearby. For example: when the new Yankee Stadium was built in Mullally Park, new parkland was created nearby to compensate for it.

Yes,Sergey finds interesting places.