If you haven’t noticed it yet in Forgotten New York, I do enjoy walking under elevated trains. You never know what you’ll find under there, infrastructure-wise; I’ve located 50-75 year old signage. Els do tend to preserve outmoded street lighting in many cases, even though the city has been stepping up its replacement program of late with LED (light-emitting diode) lamps. I’ve found Woodhaven to be something of a holdout though, in the under-the-el lighting department.

The Jamaica Avenue el was built on a very old road, at first known as the Jamaica Plank Road (and had a series of previous names, as it goes back to the colonial era and possibly before). You can see it on this 1852 Dripps atlas. Why does it meander as it does along gentle curves, instead of following a straight line? The answer is likely topography. The original road or trace went past elevations or perhaps swampy territory, and the easiest course is to simply avoid those impediments. During the Industrial Revolution, it became possible to even the ground and drain the swamps, directing any streams underground.

The Jamaica Avenue el was originally lit by incandescent pendant lamps attached to the el structure when it was extended down the avenue as far as 168th Street in 1917 and 1918 (the original section down Broadway was built from 1888-1889, when streets were lit by gaslamps). In the 1960s, when mercury bulbs arrived on the market, cylindrical Dwarf posts were built along the route, which were succeeded by L-shaped “Brownie” poles carrying sodium Holophane lamps housed in Gumballs (like the one shown above, on Westchester Avenue in the Bronxsince replaced by LEDs in many cases) and even post-top lamps along one stretch. It was the Dwarfs I was after on this walk. Was I successful? (Fear not — I’ll be discussing other items of interest I found during this walk.)

I also used to enjoy riding the Jamaica Ave el, nominally the J train, more than I do now because until a couple of years ago, it functioned as a rolling museum, the last bastion of the R-42 cars (1970) and one of the last places you could find R-32 cars (1964). However all mechanical items wear out and it was decided to retire these cars a few years ago rather than keep repairing them.

I walked Jamaica Avenue between Woodhaven Boulevard and Metropolitan Avenue. For me, it’s easy to each from Woodside by taking the Q53 express bus (on that line you need to by a ticket from a machine at the bus stop; your Metrocard is no good on the bus itself).

These post-top lamps dominate Jamaica Avenue in a stretch between 86th and 108th Streets. They are new, replacing a run of Brownies, and contain LEDs in this post-top fixture whose original design goes back to the 1970s and is in fact the dominant variety used on Type B lampposts in city parks. I suspect the Department of Transportation will be replacing all of the lamps under the Jamaica El with these within a few years, because they can be installed at shorter intervals between poles and therefore provide greater under-elevated illumination. Note that the fire alarm indicator lamp is mounted at the apex.

A visit to Schmidt’s Candy, 94-15 Jamaica Avenue east of Woodhaven Boulevard, is a bracing reminder of American capitalism and small-town pride. Schmidt’s has been producing “homemade” sweets in Woodhaven since 1925, using the same German recipes its founder employed, and the shop remains in the same family and is run by his granddaughter. It’s 2021 now, and Schmidt’s features a modern, up-to-date website, where treats like boxed assortments, assorted jellies (raspberry is a favorite), caramels, graham crackers, “turtles” made with chocolate, caramel, and nuts, and many other varieties are described and can be obtained from Tuesdays through Saturdays. Your dentist will thank you if you become a regular customer.

Unfortunately the NYC Department of Buildings cracked down on Jamaica Avenue business owners in 2018, threatening fines if their sidewalk signs weren’t bought up to code. This seems like a selective enforcement, since other parts of town hasn’t had these crackdowns; perhaps Jamaica Avenue was targeted as its signs seemed like a lucrative area. Thus, Schmidt’s changed out its 1940s-era sign sign for a new one.

95-05 Jamaica Avenue is set back from the street and the apartment house is “guarded” by a large arch, making it look palatial. It could have been built before the El arrived in 1917.

Some older signs did meet the city code and Deegan’s wine and Liquors at 96th Street apparently did. Liquor stores around town are often older by decades than any other, in plain neon or paint. Some do not even list the name of the business. They “get the job done” and don’t need to be replaced.

On this walk I passed under no less than three branches of the Long Island Rail Road, only one of which is used for passenger service. This one, the Rockaway Branch, isn’t used at all with the stretch between the main line tracks and Liberty Avenue having gone to ruin since 1962. I walked the branch with other fanatics in March 2000. There are proposals to turn it into a park, an elevated subway (like the J train) or both. None of these plans will come to fruition, certainly not in my lifetime. The Rockaway’s Brooklyn Manor station was just south of Jamaica Avenue.

I found the Alex’s Kitchen sign at 102-03 Jamaica, interesting as it consists of white serif woodcut lettering over a brown backing. Ingenious!

At Royal Cutz, 102-22 Jamaica, the owner has seen fit to wrap the post-top lamp in barber pole striping. The DOT will probably remove this as nonstandard sometime soon. Matt Green of I’m Just Walkin’ avers that the majority of barbershops around town spell “cuts” with a z, cutz. It’s traditional!

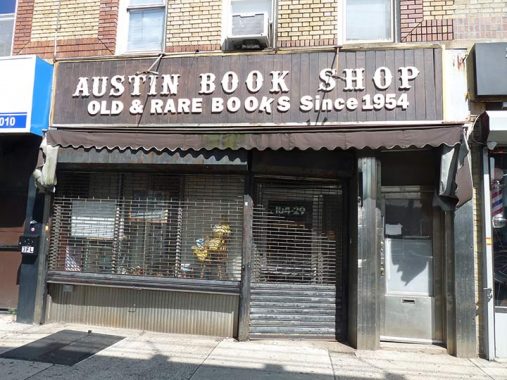

104-29 Jamaica Avenue is a long way from Austin Street, but there’s a reason for the name on this sign under the Jamaica elevated. In 1954, Bernard Titowsky opened a used bookshop in the heart of Kew Gardens, 82-60 Austin Street, and moved around the corner sixteen years later, over the years culling a devoted following even though it was only open on weekends, depending on mail order for much of its business.

Titowsky lost his lease in Kew Gardens in 1984, but undauntedly moved here to Richmond Hill. After his death in 1993, the store has been run by its next owner, Raymond Harley, who continued Austin Bookshop’s mecca status for used books on baseball that Titowsky cultivated.

This sign looks old, but it’s actually new; the DOB probably mandated one. You can see the original on this FNY page.

I found just the lamp I was seeking at 108th Street! Unique among streets under els, the DOT installed floodlight or park-style lamps illuminating crosswalks on the 1970s-era cylindrical poles at some intersections; on previous walks I counted three remaining ones, but this one seems to be the last Mohican. The city had previously placed a Brownie next to it, but failed to remove the older lamp, perhaps from inertia.

Another angle from Street View.

Abyss Hall, 108-12, is identified as a “convention hall” or “party venue” online, but calling something an “abyss” as in the bottom of the ocean, or the bottom of a curve, is rather unusual.

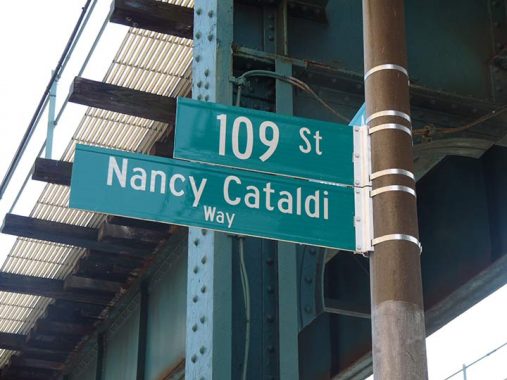

Through nearly a decade as president of the Richmond Hill Historical Society, Nancy Cataldi fought to maintain the charm of a neighborhood that was founded in 1867 and boasts elegant houses and churches. In 2002, she capped a successful campaign to landmark the classical Richmond Hill Republican Club on Lefferts Blvd., which was built in 1908 and hosted Theodore Roosevelt, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

Cataldi also led an ongoing push to turn Richmond Hill into a historic district, which would bar major renovations without city approval. A photographer by trade, she worked for the New York Rangers hockey club in the 1980s and freelanced for major newspapers and magazines in recent years. She also volunteered for a Queens-based no-kill animal shelter, Bobbi and the Strays. In 2008 Nancy Cataldi passed away at the young age of 55.

New York City, at one time or another, has had three settlements named Richmond Hill. The one in Manhattan, in what is now the west Village, and the one in Staten Island, in what is now Richmondtown, have pretty much been absorbed into new neighborhoods. Queens’ Richmond Hill has been more enduring. In 1869, developers Albon Platt Man and Edward Richmond laid out a new community just west of Jamaica with a post office and railroad station, and Richmond named the area for himself (or, perhaps, a London suburb, Richmond-On-Thames, a favorite royal stomping ground). It became a self-contained community of Queen Anne architecture west of Van Wyck Boulevard (now Expressway) that remains fairly intact to the present day. Journalist/activist Jacob Riis as well as the Marx Brothers were Richmond Hill residents in the early 20th Century.

Sneakers tossed up onto telephone wires have been a NYC staple for decades. The tradition took hold worldwide. There are varying stories as to its origin; some say the military, some weddings, some say the mob.

This stretch of Jamaica Avenue features interesting street signs in times past.

Rich signage in gold and green at 110th Street.

I thought this chalet-style building with peaked gables may have an interesting origin but after looking at a photo from 1940, no clues were offered.

So, forget what I was saying about pure inertia as the reason the MTA doesn’t remove some of these cylindrical lamps from the Super Seventies. See that green box on the lamppost? That’s the control box that controls the traffic signals. It would probably be a pain in the neck to move it, so there it stays. You can see that the brace on this one has had its floodlight replaced by an LED.

The corner building at 111-05 Jamaica has been heavily altered over the years. But the Municipal Archives shot from 1940 was taken from east of the building and doesn’t offer a view of what it used to look like.

And a pair, catercorner at 112th Street, one of them a regulation octagonal-sided pole.

Here’s an interesting wrought-metal sign for Caleta Cevicheria at 112th. “Ceviche” is a Peruvian and Ecuadorian seafood made with raw fish that has been cured in citrus fruit, most commonly bitter orange. So, the sign is in the shape of a fish. In a city of a thousand communities, walking is rarely boring.

At 113-02 Jamaica Avenue, a remaining Gumball Brownie that has been dayburning for a couple of years. Headroom is low here, as the 111th Street station is above.

Yet another dwarf cylinder with former floodlight at 114th, this one accompanied by a fire alarm lamp bracket. These posts are 50 and in some cases, 60 years old.

On 114th north of Jamaica are several buildings of interest I have featured on FNY tours.

As the Long Island countryside began taking on the character of a suburban community around the turn of the last century, a group of Brooklyn pastors saw an opportunity to establish a church of their own. They met in early 1903 to discuss founding an English Lutheran Church in Richmond Hill, which Staudermann suggested naming “St. John’s” after the St. John’s Church in Lindenhurst.

Later that same year, 56 people assembled in the old Arcanum Hall on Jamaica Avenue at 116th Street, a community center once used by many fledgling religious institutions before they raised the money to build their own churches.

A year later, the congregation welcomed its first pastor, Reverend Allen Luther Banner, who initiated plans for a permanent house of worship. The congregation held its first service in the basement of its new home at 86-20 114th Street in Richmond Hill on September 2, 1906. The completed structure was dedicated April 7, 1907. In 1923, the congregation celebrated their 20th anniversary by laying the cornerstone of the grand Gothic building next door, where services are still held today. [Queens Chronicle]

Across the street is a high-steepled Mormon church of more recent vintage…

… as well as the former Union Congregational Church Fellowship Hall, built in 1926 (see below).

PS 56, 114th Street near 86th Avenue, which appears to be the work of prolific schools architect C.B.J. Snyder, replaced a small 1894 wood schoolhouse in 1908.

An impressive Chase bank, 114-20 Jamaica Avenue. I doubt that Chase occupied the building when it was constructed, and once again the Municipal Archives photo was shot at an unfavorable angle and I can’t tell.

I know little about this shoe repair shop at 114-19 except that its owner apparently likes to build model ships.

One more former floodlight mounted on a cylindrical Dwarf at 115th.

Union Congregational Church, 115th Street near Jamaica Avenue. Inaugural services were held in 1884 and this new church was built here in 1902.In 1997 the interior of the Church was selected by Paramount Pictures for filming some scenes for the popular comedy film “In and Out”, starring Kevin Kline and Tom Selleck. The building is the present home of Global Christian Ministries.

Directly across the street from the church, a house with some interesting architectural elements. A word in a foreign language I can’t identify can be found above the upper window. Can anyone translate? Comments are open.

Another interesting bank building exactly one block east from the previous one, at #115-20 Jamaica Avenue. This one can be easily identified as the Richmond Hill Savings Bank. The bank was founded in 1920 as the Savings Bank of Richmond Hill with a name change in 1935 to Richmond Hill Savings Bank, seen here in 1940. After mergers, RHSB became part of Capitol One. This building is currently for sale.

The owners of Mi Case restaurant, and the businesses at 116-20 Jamaica Avenue before that, haven’t bothered to remove the paint store signs still there from when this was a hardware and paint store (which it was in 1940).

Founded in 1907 by the National Lead Company, Dutch Boy is currently a subsidiary of, and is owned and operated by the Diversified Brands Division of the Sherwin-Williams Company, who acquired it in 1980. The Dutch Boy symbol was painted by Lawrence Carmichael Earle and modeled after an Irish-American boy who lived near the artist.

Looking east on 117th Street, which “becomes” Hillside Avenue a block away at Myrtle Avenue and roars east as NYS Route 25B into Nassau County, eventually merging with Jericho Turnpike, NYS Route 25, on Old Westbury (with a name change to East Williston Avenue in that town). There’s an East Williston Avenue in Floral Park, Queens, which may just be a remnant of Hillside Avenue’s former name once it crosses into Nassau — I’ll have to research that.

Reclining cherub above the door of the Beaux-Arts apartment building at the SW corner of Jamaica Avenue and 117th.

I’m showing Alfie’s Pizza on 117th here because of its illuminated plastic sign, which is lit up from incandescent bulbs inside it. We will see more a bit later on this walk.

Bangert’s Flowers, 86-08 117th Street, still has some of its original 1927 sign, woith long-gone neon. I say some because much of it, featuring the Roman God Mercury, the symbol of FTD Flowers By Wire “the Mercury Way”, was removed some years ago; I think it was used in props for a movie or TV show. FTD stands for “Florists’ Telegraph Delivery” and was founded in 1910.

Bangert’s Flowers, on 86-08 117th just west of Myrtle, started out as Fluhr’s in 1894 and was sold to the Bangert family in 1927.

I have told thr story of the Triangle Hotel, maned for the shape of the plot it occupies where Jamaica and Myrtle Avenues meet, often on the tours and in Forgotten NY. The most visible traces of the hotel can ebe found on the Jamaica Avenue side.

Almost as long as there’s been a Richmond Hill, the Triangle Hotel building has marked the triangle where Myrtle Avenue meets Jamaica Avenue. It was built by Charles Paulson in 1868 and was originally rented out as a grocery and post office. By 1893 the building, now owned by John Kerz and operating as a hotel, included an eatery named the Wheelman’s Restaurant in honor of the new bicycling craze. The hotel began lodging weary travelers going east on Jamaicsa Avenue in the days before the LIE or the Belt Parkway from New York City or coming west from points on Long Island and has been known under various names through the years: the Mullins Hotel, Doyle’s Triangle Hotel, Waldeier’s Triangle Hotel, Triangle Hofbrau, and Four Brothers. Its mahogany bar was imported from Honduras, and a brass bell rang every time a round of drinks was purchased.

According to the Richmond Hill Historical Society, Babe Ruth (who was a golf enthusiast in nearby St. Albans) and Mae West were patrons of the Triangle Hofbrau in the 1920s; Miss West was routinely ejected for smoking (shocking!) and causing a “general commotion.” Vaudeville pianist/composer Ernest Ball (1878-1927) wrote the now-standard “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” in one of the hotel’s guest rooms in 1912. A restaurant operated continuously in the Triangle building from 1893 to 1999.

More than one Forgotten NY tour’s “postgame show” has been held at the Classic Diner across Myrtle Avenue from the Triangle. This was the site of the Richmond Hill Palace, billed as “Richmond Hill’s new quarter of a million dollar pleasure palace” when it opened in 1925. James Kendis’s Blowing Bubbles Orchestra provided the music; Kendis wrote the pop song “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.” Helen Keller was a prominent guest the first year.

The wines and liquors store here at 118-04 is on the ground floor of what was once a private house. Perhaps the owners still reside on the top floors. Note the traditional plastic lettered sign.

The second Long Island Rail Road crossing on Jamaica Avenue at Lefferts Boulevard, this was actually the Richmond Hill passenger station on the line until 1998, when service ended and the line completely given over to freight. The 121st Street station on the Jamaica el is two clocks east; I’ve said often that this has the potential to be a transit hub if they ever revived passenger service on the LIRR and connected the two stations, but I’ve been reminded just as often that there is a connection at Sutphin Boulevard on the Archer Avenue line to the east, making such a connection redundant.

The Happy Days Lounge, 118-16 Jamaica, is in a venerable building that has its date of construction, 1899, atop the roof in a cornice. In 1940 this was home to a Sweet-Orr Army-Navy store.

The Triangle Pharmacy, NE corner of Jamaica and Lefferts, is a reminder of the old Triangle Hotel (see above).

Rubie’s, which calls itself the largest costuming company in the world, was founded in 1951 by Ruben “Rubie” Beige and his wife Tillie as a small neighborhood novelties shop and was expanded as a franchise in the 1970s by their son Marc. The flagship store is in this brick warehouse at 120-08 Jamaica Avenue.

Mañana Grocery, 125-19 Jamaica Avenue, has another of those 1960s or 1970s illuminated plastic signs I have been pointing out.

At 129th Street, the el diverges off Jamaica Avenue and quickly descends into a tunnel beneath Archer Avenue. The short section connecting the el and the tunnel, built in the 1980s, gives you a glimpse of what elevated subway lines would look like if they were still being constructed today.

Metropolitan Avenue, constructed in 1814 as the Williamsburg and Jamaica Turnpike when it carried horses and carts, ends its 12-mile run from the East River at Jamaica Avenue just short of the Van Wyck Expressway. I walked its length in the spring of 2015.

The Jamaica-Van Wyck subway station, serving the E train, was opened on December 11, 1988, along with two other stations: Sutphin Boulevard and Parsons-Archer. Along with the J line underground extension to Parsons-Archer this was a joint effort to link the Queens Boulevard line (now serving E, F, M and R trains) with the Jamaica Avenue El in Jamaica; after the el was truncated to the 121st Street station from its original length out to 168th Street, a new tunnel was built to take the J to a new terminal at Parsons Archer where it met the E train.

All this was supposed to be part of a much lengthier route which would take the E or J to southeast Queens (think Rosedale or Laurelton) via a little-used section of Long Island Rail Road track, but funds dried up in the 1970s and that stretch of track remained with the senior railroad.

This station also marks the southern end of Kew Gardens Road, which connects Metropolitan and Jamaica Avenues with the junction of Queens Boulevard and Union Turnpike. It is a very old road going back to the colonial era and was originally called Newtown Road. When Queens was consolidated with NYC in 1898, some street names were changed to avoid confusion — there was already a Newtown Road in Long Island City.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

9/12/21

10 comments

Great posting, thanks for sharing. Just one correction, from the very last section. While it’s true that the Archer Ave. subway was indeed supposed to be part of a much lengthier route which extend subways to Rosedale or Laurelton using the LIRR right-of-way, that LIRR route is not a little-used section. It is a heavily used stretch (the Atlantic Branch) that carries Long Beach, Far Rockaway, West Hempstead, and some Babylon Branch trains. There is a parallel LIRR Branch to the east (Montauk Branch), and both meet again at Valley Stream, but both are needed for maximum service (at least pre-Covid). Putting subways along this stretch would have required expanding the current embankment from two to four tracks, which would have been an engineering challenge. Also note that the Metrocard’s introduction in 1997 eliminated the double fares in this area, although it’s still necessary to transfer to buses at Parsons-Archer in order to reach Southeast Queens by subway.

Full disclosure – I am a retired LIRR manager and still travel this segment between Nassau County and Jamaica on a regular basis.

Correct me if I’m wrong but isn’t Railroad park (recently renamed Gwen Ifill park) next to the Locust Manor station where they planned to build a subway yard for this intended service?

Probably not, because Locust Manor would not have been the end of the subway had it been extended to Southeast Queens, Terminus would have been near today’s Laurelton or Rosedale LIRR Stations, because yards need to be at the ends of routes. The Southeast Queens subway proposal died long before it got to the level of detail where a storage yard location was researched.

Are you talking about the same location where there is new high-rise residential construction on the east side of the LIRR tracks near Locust Manor? Noticed it last week when I rode past on the LIRR.

For holidays and other special events I’ll order from Schmidt’s and have it shipped to me – love their candy!

I grew up on 90th St north of Jamaica Ave in the 50’s. There was another Schmidts Candy store/luncheonette on Jamaica Ave @ 90th St. I can still remember the smell of the chocolates. Jamaica Ave was originally an old

Indian trail, which is why it isn’t a straight road like Atlantic Ave.

I have always wanted to live in one of those corner apartments that had a round turret type

corner to it like the one at 111-05 Jamaica Ave.preferably on the top floor.I imagine it would

be like living in a lighthouse and be very cozy.If I was a writer I would set up my typewriter

in it,If I was a artist I would get all that sunlight in which to paint.They probably get quite

hot in the summer but thats what air conditioning is for.

Sneakers hanging from wires means that drugs are available in the vicinity.

We threw our sneakers on the wires walking home from our last day of school

Great post. Interestingly enough back in the 80s there were plans being floated to eliminate the Jamaica el either east of Crescent Street or Broadway Junction and instead hook the lower level of the Archer Ave line into a new subway route to be built along the LIRR Montauk spur to connect with the 63rd Street tunnel in LIC. Thankfully never came to pass.

The Chase Bank at 114-20 Jamaica Avenue was bought by them on December 7 1932, as evidenced by the 1998 deed referring to the sale. It is available in the ACRIS system. https://a836-acris.nyc.gov/DS/DocumentSearch/DocumentImageView?doc_id=FT_4690006236469