PLENTY of people say never look back, only look forward. I have never heeded that advice. I’m always replaying events, both good and bad; I remember slights from decades ago. I never forget, but I forgive. Back in 2017, I scanned in a number of photos from the dawn of the Forgotten NY era, from 1998-2001. Back then, I was photographing things that still existed but New Yorkers seemingly hadn’t noticed them or didn’t care about them.

Fortunately, there are plenty of people who do care and this little website is still going nearly 25 years later, with more than 150 live tours, a number of personal radio and TV appearances (one night I staggered into a hotel room in Calgary to find myself on the TV news speaking at a confab about the reuse of alleyways (not sure if the king of CTV News, Lloyd Robertson, introduced the segment; I should have worn a better shirt) two books and a chapter and newspaper articles (I once appeared “above the fold” in the NY Times; below the fold were David Brooks and Paul Krugman.)

When I began photographing for Forgotten NY I was a rank amateur and didn’t know how to get the best possible shot. I am still a point and shoot photographer and haven’t realized the potential of my digital cameras and IPhone cameras. Nevertheless, my technique was good enough that I photographed everything in Forgotten New York The Book from 2006 (the HarperCollins production crew snazzed things up and gently retouched some material). But the passage of time has rendered these pictures an added effect of regret since many of them have disappeared in the 25 years since I first grabbed them.

You’ll also notice vivid Kodachrome colors here; digital photos have a flatness to them, and while I do retouch in Photoshop occasionally, I can’t get these kind of bright colors without laboring in the digital world longer than I want to.

Depending on stamina I will likely make this a two-parter; as I’ve said on occasion, the days when I do 75-100 photo page extravaganzas are mostly over…

This is really the only piece of the 9th Avenue El, which ran until 1940, remaining. A short segment of the el ran as a shuttle from the Polo Grounds to the Jerome Avenue El north of Yankee Stadium (here on River Avenue) until 1958; this segment actually partially ran in a tunnel beneath the western Bronx’s hilly topography. In 1999, I and a group of subway mavens walked through this pitch-black tunnel past the shuttle’s old Sedgwick Avenue and Jerome-Anderson stations. The NYPD subsequently sealed the tunnel, which had become repository for trashed automobiles.

The New Yankee Stadium now occupies most of this spot and eliminated the portion of East 162nd along the chain link fence.

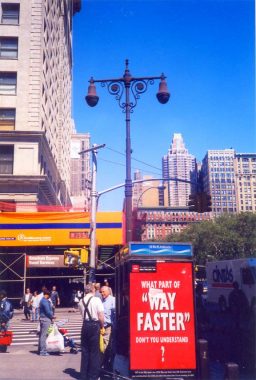

The corner of 23rd Street and 5th Avenue at Madison Square quite serendipitously became a repository of the castiron Twinlamp design, with one on the NW corner, one in the traffic island (both of which are still there) and this one, which was dispatched by a truck by 2008. Conversation on 5th Avenue: I wonder what those two guys were talking about all these years later. The “way faster” ad probably refers to cell phone connections; today’s speeds put 2000’s to shame.

The building in the rear is the (200) 5th Avenue Building, which had longtime offices of toy companies. I worked in the Tiffany & Co. offices there from 2013-2014.

When I moved to Flushing from Brooklyn in 1993, there were still some remaining color-coded by borough NYC street signs around. These were introduced in 1964 and anyone knew what borough they were in by the color of the street signs. This wasn’t especially important except where boroughs had a land border such as Brooklyn/Queens and Manhattan (Marble Hill) and the Bronx. Manhattan and Staten Island were yellow with black letters; Brooklyn, black with white letters; Bronx, blue with white letters; and Queens, white with blue letters. By 2023, very few, if any, remain. I found these at 39th Avenue and Glenwood Street and on 58th Avenue at Utopia Parkway and Booth Memorial avenue, named Atlantis Triangle by former Parks commissioner Henry Stern.

NYC replaced the color coded system with green and white signs beginning in the early 1980s, though some business districts such as Downtown Alliance in lower Manhattan have special signs.

Before McDonalds, Wendy’s and Big Boy, quick, cheap and tasty food was the province of the Automat.

Horn and Hardart’s Automats provided cheap, quick lunches to generations of New York’s office workers. Arising at Art Deco’s height in the early to mid-1930s, Automat interiors greeted customers with sleek, functional graphics: row upon row of glass cabinets containing sandwiches, soups and slices of pie; the cabinets would unlock when a nickel was fed into a slot. Coffee would be dispensed by dolphin-headed founts, and there was a steam table dispensing hot food and more substantial fare. The food, while not of the quality of a sit-down restaurant, was nevertheless substantial and good-tasting; there was a surprisingly large variety of choices, and at a nickel in the early days, the price was right. Horn and Hardart was renowned for using fresh food daily; no day-old leftovers were used at the Automat. At their height, Automats served 800,000 people per day.

Automats originated in Philadelphia in 1902 and debuted in NYC in 1912. As American palates changed after World War II, Automats very gradually decreased in clientele, but it wasn’t until 1991 that New York’s last Automat, at 3rd Avenue and 42nd Street, closed its doors.

A couple of remnants of Automats long-past remain around town, however. A former neon Automat sign could be found here on Willoughby Street between Pearl and Jay Streets; I had meant to include it in the ForgottenBook when I was furiously composing it from 2003-2005, but it vanished soon after I grabbed the shot in 1999.

In midtown Manhattan, a painted ad on West 38th Street near 7th Avenue still bills an Automat that was nearby. In 2022, filmmaker Lisa Hurwitz put together a reminiscence of the Automat featuring Mel Brooks and other personalities who remember the Automat.

These painted ads for a bowling alley on Rockwell Place behind the Strand Theater on Fulton Street in downtown Brooklyn were there until about 2013. The Strand and neighboring Majestic, now part of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, was renovated in the early 2010s and the bowling mural was power-washed off the building.

By 1958, the theater had become the property of the Metropolis Bowling Center, and was called the Strand Lanes. The bowling alleys were there until at least the 1960’s, when the entire building became manufacturing space. — [Montrose Morris in Brownstoner]

There was once a row of theaters along Fulton Street in the area, of which the former Strand is the survivor.

These lampposts, dubbed the Whitestones by former NYC King of Lampposts Jeff Saltzman (he lost his crown when he moved to North Carolina, and the title is now held by Robert Mulero) because this design was once used by the thousands on NYC parkways and expressways and apparently debuted on the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge.

I found these on the Roosevelt Island Bridge at Vernon Boulevard and 36th Avenue in LIC; of course they were replaced several years ago. Today, a few of the “Stones can be found on Sands Street near the Brooklyn Bridge, ramps connecting the Brooklyn Bridge and FDR Drive, and a lone specimen at 3rd Avenue and a BQE exit at 17th Street in Park Slope (seen here), but that’s about it.

This ad for Burnham’s Beef Wine is still visible, though less so after 25 years, on Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District near Washington Street. When I took the photo, “the Meatpacking” was just beginning its transformation away from meat wholesaling to retail and tourism. However, the Meatpacking had a nightlife long before that as by night there were gay and lesbian clubs in the area. A great French-American restaurant below the sign, Florent, had its feet in all of the Meatpacking worlds as it served the clubgoers, meat mechants and tourists and somehow, all felt welcome. A rent increase took it out in 2008.

When I first saw this painted sign I naturally assumed it said “Burnham’s BEET Wine.” Actually the T is an F. “Beef Wine” was a patent medicine popular in the 1900’s, comprised of port wine fortified with beef extract and iron, not unlike the tonic “Hadacol” that was so popular in the Deep South in the 1940’s which was Iron and a Vitamin B complex in a 12% alcohol base. In this area formerly filled with slaughterhouses and meat wholesalers, “beef wine” is appropriate.

The Indispensable Walter Grutchfield:

Burnham’s in New York began as E. S. Burnham Co. Manufacturers Grocers’ Specialties at 120 Gansevoort St. around 1894, and moved to 53-61 Gansevoort in 1897. They were located here until 1929. Their products were groceries, produce, and druggist sundries. Apparently the sundries included medicinal tonics and extracts, as well as clam bouillon.

This is the top of a flyer for Burnham’s Great Restorative Tonic combining beef, wine and iron. The bottom of the same flyer mentions Burnham’s Clam Bouillon.

Regarding Burnham’s bouillon The American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record of 8 October 1900 (vol. xxxvii, no. 8) wrote, “It was conclusively proven in the Spanish-American War that the Clam Bouillon of the E. S. Burnham Company was an invaluable preparation, both as a food and as a tonic. When arrangements for supplies for hospital use were being made by the Red Cross Society, and careful investigation was made by the society into the respective merits of every product, the E. S. Burnham Company was among the favored number and received a small order for their Clam Bouillon. Within a short time they received duplicate orders … With the public Burnham’s has been a popular article for several seasons…”

In the 1890s industrialist Irving T. Bush (1869-1948) constructed a manufacturing empire along the Brooklyn waterfront served by rail and steamships.

White-painted monoliths, now known as Bush Terminal and then Industry City, were constructed by architect William Higginson in the first 3 decades of the 20th Century for the Bush empire between 29th and 36th Streets and 2nd and 3rd Avenues. There are 15 lofts in total, each 6 to 8 stories in height, fully 200 acres of land given to vast warehouses and manufacturing lofts. Bush Terminal had a waterfront railroad and 18 deep water piers.

Today Bush Terminal is becoming a beehive of activity in the telecommunications field, as many of its buildings are being converted by Industry City Associates into broadband services providers and later, retail and restaurants.

A statue of the industrialist, dedicated in 1950, can be found on one of the railroad terminal buildings at the entrance to the new Bush Terminal Piers Park at 43rd Street west of 1st Avenue.

Here’s a comprehensive look at the man and his empire.

I always had something of an affinity for Market Street, which sidles up to the Manhattan Bridge’s south side and runs for a few blocks from Division to South Streets amid a rapidly expanding Chinatown. When laid out it was known as George Street, but it was changed after the American Revolution as NYC barred place names associated with the Crown; thus Queen Street became Pearl, etc. Not all, though, as Prince Street in SoHo and Fort George uptown attest (King Street is named for Congressman and ambassador Rufus King, whose mansion in Jamaica is now a museum).

Market Street widens considerably between Cherry and Market Street as it becomes Market Slip. Like other Manhattan downtown “slips” it is wide because it was formerly a watercourse allowing ships to dock. The dock here, at George/Market Street, was the site of Catherine Market, a large produce market that is long vanished but donated its name to George Street to eradicate any British leftover influence. This is perhaps the most boring section of the street but it does allow for views of both the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges. The New York Post was formerly headquartered in the large loft at South Street and Market Slip.

Till the wall was whitewashed several years ago, this classic Fletcher’s Castoria ad could be seen at #13 Market Street in the shadow of the Manhattan Bridge.

259 Front Street, on the corner of Dover, is one of the oldest houses in the South Street Seaport area. It was constructed in 1808 for flour merchant David Lydig (as were other buildings in the area). Lydig owned a fleet of schooners that would carry flour from his upstate mills to a dock, or slip, on Dover Street. He had the foresight to sell his flour empire and take a profit when he learned the Erie Canal was under construction. The rest of this block is occupied by a huge Con Ed transformer station built in 1975. Lydig has an avenue named for him in Morris Park, Bronx.

In 1999 the ground floor business was a bar/restaurant called Radio Mexico and later Mexican Radio, named, no doubt, for the 1982 hit record by Stan Ridgeway and Wall of Voodoo; it has since moved to Cleveland Place in NoLita. By 2014 there was a bar called Cowgirl Sea Horse on the ground floor here. One block west on Water Street, the Bridge Cafe had been in business as a bar in one form or another since the 1700s, but it has been closed since Hurricane Sandy in October 2012. In 1971, this corner was featured in the cop classic The French Connection.

No doubt, what moved me to take this photo was also the unusually-configured Donald Deskey lamppost on the corner: it’s bent and configured unusually, and still had an original fire alarm indicator lamp. It has since been replaced by a retro Bishop Crook.

Note the star-shaped appendage on the lower right. It is the end of a metal tie rod used to support brick buildings before iron and steel frameworks began to be employed. In the Seaport they were fashioned to look like starfish.

Information from Walking Around in South Street, Ellen Fletcher, South Street Seaport Museum 1974

In this photo on White Plains Road and Gun Hill Road, the infrastructure for the north end of the old 3rd Avenue El was still in place, along with enamel 3rd Avenue platform signs. Until 1973, the Third Avenue ran as a shuttle (the #8 train, though never signed as such on the cars) north on Third and Webster Avenues, turning east on Gun Hill Road and merging with the White Plains line here. The infrastructure remains today, though the platforms have been removed.

When I first encountered the ruins of the old New York Cancer Hospital, completed in 1886 in a French Renaissance style at 455 Central Park West at West 104th Street, it was still very much the magnificent ruin it had been since 1976, when it was last in use a nursing home. It had once been one of NYC’s leading centers of cancer treatment, introducing the use of radium in 1920, eventually evolving into today’s Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

During its long period of slumber, Ian Schrager, formerly a partner in Studio 54 and now a leading NYC developer, tried and failed to resurrect the building to glory, and Q, The Winged Serpent, left an egg in there in a 1982 film.

At length Daniel McLean, president and chief executive of the MCL Companies in Chicago, purchased the property for $21 million in 2000. The 9/11/01 terrorist attacks stalled the redevelopment temporarily, but when Columbia University bought several floors to house visting dignitaries and senior faculty, 455 Central Park’s survival was finally assured. The old facility’s circular rooms and spaces, built to discourage the accumulation of dust and the proliferation of germs, are now the centerpieces of residences that sell for $7 million or better.

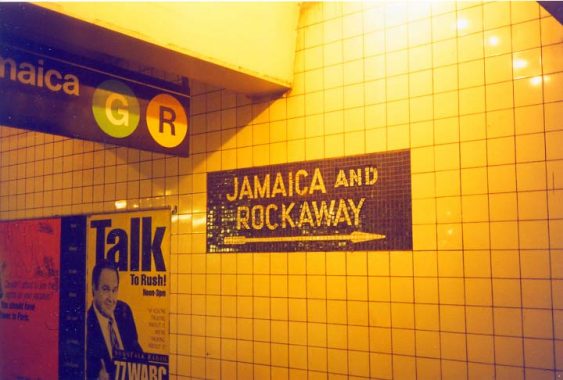

Plenty of history here in 1999. Until 2010 the G train ran all the way to Continental/71st Avenue on the Queens Boulevard line. The late conservative talk show host Rush Limbaugh held forth for three hours, 12-3PM, on WABC; his show later moved to WOR.

When the Queens Boulevard line was opened from 1933-1936, the Independent Subway had every intention of expanding further, crossing Jamaica Bay en route to the Rockaways. However, World War II stopped NYC subway expansion. The IND eventually did reach the Rockaways, but via the Fulton Street IND (A train) as the city purchased the burned-down LIRR Jamaica Bay trestle, rebuilt it, and ran subway service across beginning in 1956. This sign at 65th Street was placed in anticipation of Rockaway service on the Queens Boulevard line that never materialized; a branch would have ran south through Elmhurst, Maspeth, Glendale and Woodhaven. Those areas have never received rail service in the modern era and by now many of its residents say they can do without it.

Keal’s Carriage Manufactory (“factory,” basically) helped get the ball rolling for Forgotten NY when this ancient painted sign was exposed briefly when a corner building at Broadway and West 47th Street (Duffy Square) was torn down in 1998. The Times Square area, before it was an entertainment mecca, was home to the horse and carriage trade; Keal’s, likely from the 1878-1885 period, was one of them. A new building quickly went up and the sign may still be there, underneath.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

10/1/23

12 comments

The only problem with Automats is that you sometimes had to share a table with

a total stranger.Some people couldnt take this arrangement,if someone sat down

at their table they immediately got up and left,

Automats wouldnt last long today.The way people are now fights would break out

right and left.

“Excuse me,I was sitting there.Why did you take my seat?”

I don’t know. I have been in cafeteria style seating places and witnessed no issues.

Where?Where do men still gather together and break bread in fellowship?Burger King?

As usual, another great posting. Hope you are doing well and getting around OK.

Two comments. First, regarding the 3rd Avenue Elevated at Gun Hill Road, should note that the shuttle route operated 19th St.-Gun Hill Road between 1955 and 1973. Until 1955, the elevated operated through service all the way to Chatham Square; and until 1950 service ran to South Ferry, atop the current R/W and #1 trains.

Second, regarding the Queens Boulevard line extensions to the Rockaways, there were two possible routes. One alignment would have ran south through Elmhurst, Maspeth, Glendale and Woodhaven, beginning at a stub station at today’s Roosevelt Avenue-Jackson Heights stop. The second proposal was to build a connection just east of today’s 63rd Drive stop to connect with the Long Island RR right of way that has been abandoned for over 60 years but was once the trackway that connected Penn Station to the Rockaways. This is the same right of way proposed for a High Line type walkway today. In 1933 NY City almost bought the old LIRR route, and east of 63rd Drive there is a turnout in the tunnel (called a bellmouth) to accommodate a future connection. South of Liberty Avenue the rows. is of course still in use, part of the subways since 1956.

I meant “149th St- Gun Hill Road”, not 19th St. Mea culpa – sorry!

Kevin, I, too, am happy to see you busy posting. I trust all has gone well with your surgery. I’ve been through the same twice, and they are both just memories.

I loved the Automat, having gone many times with various grandparents in the 1950’s and 1960’s. I am sure that neither grandparent would have taken me to anyplace that had any degree of insecurity. I fondly remember going to the “cage” where a cashier would sit and dispense coins in change for use in the dispensers. I marveled at these folks, who were veterans of their craft. In a swift motion they would dispense exactly the correct number of coins from their hand and move on to the next transaction. There were no machines to spit out the nickels, dimes and quarters, just muscle memory and experience. My grandparents always got cups of coffee, which were dispensed into the coffee cup from a spout that looked like seahorse. My parents would take us to the Radio City Musical Hall for the Christmas Show and we would feast at the Automat across 6th Avenue.

My family frequently ate at the Willoughby Street Automat when I was young. I was fascinated by the milk dispensers. And the way an entire panel of door locked in unison so they could be restocked.

I take it that most of what is shown on this page may no longer around now.

Why do you think that?

October 3, 2023:

The day I learned that Kevin Walsh is, apparently and self-admittedly, NOT the “NYC King of Lampposts”!

(…but I’ll always *think* of him that way, regardless…)

Unfortunately, I never got to experience what it was like at an automat especially since most of them were gone by the time I was born.

Though by no means the focus of your piece, I’m glad someone — you— remembers FLORENT, a delightfully quirky late night spot that attracted a delightfully off-beat crowd. Haven’t come upon another spot quite like it.