At the height of Manhattan’s decades as a maritime shipping hub, there were 99 numbered piers between Battery Park and 59th Street. Each one represented a specific freight, passenger, and ferry company. With container shipping relocating to the larger harbors in Newark Bay and Staten Island, and air travel overtaking trans-Altantic passenger liners, most piers along the Hudson River became vacant, eventually demolished with a few pilings left as evidence of their existence. Those that remained standing became warehouses and garages.

On a cold January morning, a coworker invited me to attend an environmental conference at Pier 57, where I met people representing schools, nonprofits, and agencies. Besides the repurposed pier and the event, I got to see the Hudson River covered in ice, a rare sight.

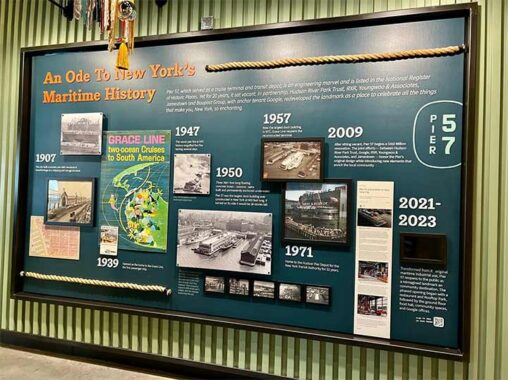

This pier replaced an older pier constructed in 1907 for the Grace Shipping Company, whose namesake founder William R. Grace, the city’s first Roman Catholic mayor, served two nonconsecutive terms in the 1880s. The company also operated out of neighboring Pier 58. The original Pier 57 burned in 1947, a two-day blaze costing $5 million.

The present Pier 57 was completed in 1954 by the city’s Department of Marine and Aviation whose tasks were later divided between the city’s Economic Development Corporation and Department of Transportation. Along with Pier 40 it represented a final chapter in the West Side’s long history as a port of call for oceangoing vessels. At the time these piers were regarded as state of the art, structures deserving of high-profile groundbreaking, ribbon cutting and front page headlines.

The west side of that time would be unrecognizable to today’s visitor: the High Line is a linear park, the Miller Highway is a boulevard. Chelsea Piers, Little Island, Hudson River Park, and much more. Since the turn of the millennium, nearly all of the remaining piers were absorbed into the park and repurposed for recreation, entertainment, and work. In the entrance lobby of the pier, the ramp leading to the events space was built for trucks that parked on the upper deck and rooftop.

Pittsburgh is famous for funicular railways but there are none to conquer New York’s slopes, only a handful of step streets further uptown. Its closest relative is an incline elevator and there are only two of them in this city: the Hudson Yards subway station and Pier 57.

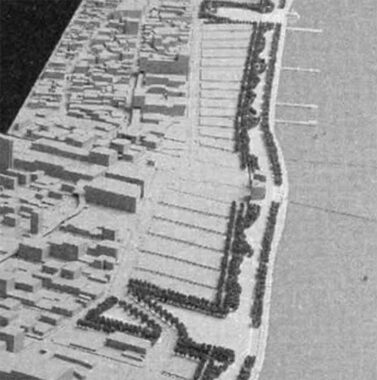

In the 1980s there was a plan to expand the city by one more block into the Hudson River as part of the Westway project. It would have meant demolishing every pier along the West Side Highway. The leading reason for its cancellation was ecology.

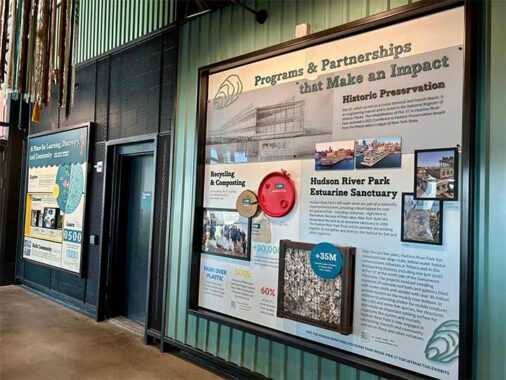

A display shows the ecological impact of the power, efforts to restore the harbor’s oyster population and the creature’s role in this ecosystem.

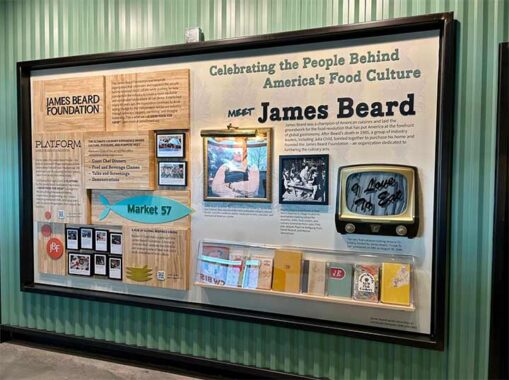

Alongside Google’s offices and Hudson River Park classrooms, Pier 57 is also anchored by its food hall, curated by the James Beard Foundation. Its namesake founder lived nearby in Greenwich Village. The pier was also slated to host Anthony Bourdain if not for his untimely death.

Visitors can work where they eat with plenty of sockets for laptops in view of Little Island, the privately built park standing on the site of Pier 54, where the survivors of the Titanic landed in 1912 and the ill-fated Lusitania was supposed to arrive here in 1915.

On a snowy day, an indoor playground is ideal. The swinging bench looking south offers a view of the Hudson River opening into the harbor with the Statue of Liberty in the distance.

The top of the pier, 900 feet into the river points towards Jersey City and Hoboken. The latter is a tight municipality of 19th century streets and the latter has high-rises built in the first quarter of this century on former railyards. Accessible by ferry and the PATH train, Jersey City feels like an extension of New York.

Hoboken’s shoreline stands out in account of Castle Point, the highest point in that city. North of this hill is Elysian Fields, the park where Vice President Aaron Burr fatally shot Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Inventor John Stevens has a prominent role in the city’s founding: he chose its name from a Native description, and purchased land atop Castle Point which became Stevens Institute of Technology.

Looking north, towards the Chelsea Piers golf driving range on Pier 59, pilings mark the site of Pier 58. Like ghost streets on the map, stanchions of demolished elevated lines, and ramps for unfinished highways, these remnants testify to the west side’s busy past as a seaport. Too costly to renovate and having lost its purpose, Pier 59 was demolished in the 1970s.

As seen in this view from the Miller Highway, Pier 56 had a classicist design identical to the original Pier 57 and Chelsea Piers. They had the same design firm, Warren and Wetmore, and Beaux Arts style, as Grand Central Terminal. These piers served transoceanic passengers until 1958, with the last freight ships docking here in 1967. Chelsea Piers underwent a $100 million transformation in the 1990s, hosting venues for sports, entertainment, and film studios. The golf net at Pier 59 stands at 160 feet, the only driving range on the island of Manhattan.

In a neighborhood better known for retail, fashion, and tech, food and drinks are still being made here. City Winery on Pier 57. Massive barrels and winemaking equipment show that things are still being made in New York, albeit with less smoke in the atmosphere.

Not since the skyscraper craze of the early 20th century have so many new city rooftops opened to the public: Edge at Hudson Yards, Summit at One Vanderbilt, Elevated Acre, Whitney Museum, and dozens of rooftop bars. Pier 57 has a rooftop park with space for performances. On my visit, it was covered with snow but having spent my childhood climbing fire escapes and opening alarmed doors to access the tar beaches of Rego Park, I appreciate an accessible rooftop.

Visiting Domino Park, IKEA in Red Hook, Gantry Plaza, and Bush Terminal Park, I enjoy parks that preserve their industrial history. In the adaptive reuse of Pier 57, the rooftop park preserves the gantries and green paint from its past. Kevin Walsh can also appreciate the preservation of the wall-mounted lamps facing the West Side Highway.

Is a structure listed on the National Register of Historic Places, with Google and James Beard Foundation as its tenants, worthy of Forgotten-NY? Certainly, because there are plenty of New Yorkers who haven’t been to the redeveloped West Side, unaware that the passenger and freight ship terminals of old have a new life as hubs of creativity and destinations for recreation.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

2/7/26