It all started when I got wind of an ancient painted ad revealed on the corner of 5th and Flatbush Avenue from a tip from Paul Lukas of ESPN and Uni Watch fame. As you will see the ad is choice indeed. 5th and Flatbush is a corner I passed just about every day from 1971 to 1975 and frequently again from 1975 to 1980, as I used the B63 bus on 5th Avenue to get to high school (Cathedral Prep) and then college (St. Francis). In just the past few years the landscape in this part of town has irrevocably changed.

I decided to see the ad for myself, and the day evolved into a trip across the Brooklyn Bridge to Manhattan’s Municipal Building.

5th Avenue “begins” at Flatbush Avenue now, but it used to run through to Atlantic Avenue, where it encountered meat processing plants, Brooklyn’s answer to the Meatpacking District; I remember walking past raw meat swinging on hooks when walking east on Atlantic. The old Long Island Rail Road Flatbush Avenue terminal, constructed in 1907, still stood. In the triangle formed by 5th Avenue, Flatbush and Atlantic stood the old Underberg kitchen supplies building and an adjacent used car lot. Beginning in 2010, construction for the Barclays Center sports and concert arena wiped all that away, while the Atlantic Center shopping mall and new LIRR terminal occupy the north side of Atlantic. Development in that area was quite slow to materialize, though, and the old LIRR site was a hole in the ground for the better part of 20 years between the 1980s and 2000s. The new Pacific Park housing complex is slowly taking shape east of Barclays Center; it continues to disrupt the region, and forced out many longstanding area residents.

Google Street View of 5th and Flatbush from May 2012. This building does not appear to be particularly old, but I remember a different story from my high school years. There was a building there crowned with a number of terra cotta parapets. That building was either razed or its terra cotta was stripped off. This building was razed in November 2017, revealing the old painted ad on the building on Flatbush Avenue that now hosts Shake Shack.

When I first heard about that ad, I was concerned that the old Triangle Building across the street, home of the original Triangle Sporting Goods store, had been torn down, but thankfully it’s still there, though the sporting goods place is long gone. Flatbush Avenue cuts across the grid, producing a number of triangle-shaped plots.

This is what the plot looked like in November 2017. You can see the ad in question on the side of the Shake Shack building. I had never pegged these buildings to be of great age, but it now appears they go back to 1880 or so.

So, here’s the ad in question. It’s a “palimpsest,” or a group of faded painted ads that were rendered at different times on top of each other. As the paint wears away, different painted ads are revealed. Some of the corner brick building is still in place and awaiting demolition, so only part of the ads are revealed to the air.

Dominating the space is a very large ad for a picture framing business. It’s easy to make out the letters ILL and “Picture Framing.” If you look closely, you can also make out the letters N and E, so it’s likely O’Neill.

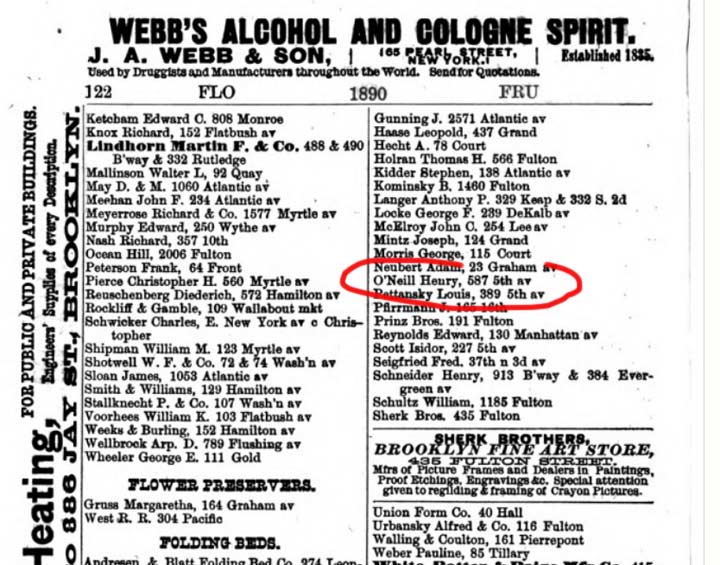

If you look at a handy dandy copy of Lain’s Kings County Business Directory from 1890/91, you can see a listing for O’Neill Henry under Frame Makers. Now, 587 5th Avenue is close to 16th Street in Park Slope, but it’s entirely possible that this was an advertisement for that concern. O’Neill must have had plenty of dough on hand for this large an ad.

A look at the south end of the ad. Most of this is illegible except for the two words “quick lunch” at the top.

I took some photos to put the frame ad in context with surrounding latterday objects. It was my usual bad luck to come by around 12:30 PM, a time when a shadow obstructed half the ad, and in November, the sun angle makes the shadows harsh indeed. I used Photoshop to lighten up the contrast a bit.

Here, at right, you can see One Hanson Place, Brooklyn’s tallest tower for decades, since surpassed by a few buildings that opened in the 2000s. Originally it held offices for the Williamsburg(h) Bank and other tenants and opened in 1928. It’s still the tallest 4-faced clock tower in the USA.

This is through a square hole in the plywood fence surrounding the demolition site. The local youth have already been drawn to it like flies on sherbet, hence the yellow paint mark. Here the ad is contrasted against one of the 2000s Atlantic Terminal buildings.

Seen here, of course, is the faux rust of the Barclays Center which opened in September 2012 with a Jay-Z concert. The Brooklyn rapper and media mogul was also temporarily invested in the Brooklyn Nets, whose opening day at Barclays was delayed by Hurricane Sandy.

A look at the Triangle Building at 5th and Dean, Barclays Center, and one of the Pacific Park towers, 461 Dean. Rental units there cost about $3800 a month, and sadly, that doesn’t sound outrageous for a monthly rental in Brooklyn anymore. Interiors, which admittedly have great views, can be seen at Curbed.

Dean Street and 4th Avenue, where you can find one of NYC’s mostly ineffective push button signal changers. I still have no idea what these were meant to do, since if pedestrians were put in charge of changing stop signs from green to red, innumerable traffic accidents would happen! I’m showing it since the “Dept of Traffic” notation because it indicates the sign’s age.

Between 1950 and 1977 the city’s roads were maintained by the Department of Traffic, which had taken over the responsibility from the NYPD. The board was reorganized in 1977 as the Department of Transportation.

A grouping of interesting buildings on 4th Avenue’s west side between Dean and Pacific. The corner building, home to a Halal Chinese Food enterprise (this is New York, kids) has roof corbelling and corner quoins marking it as from the late 1800s; the center building has a nifty polygonal bay window, allowing residents to see north and south; and there’s a building with an 1870s-style mansard roof with scale tiling and exterior art for the Townhouse Art Gallery.

One day I’m going to do an item on all of New York City’s classic library buildings — awhile ago I obtained a list of all the remaining libraries from the early 20th Century that were part of the grant provided by industrialist/philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. This, the Pacific Branch at 4th and Pacific, opened in 1904 and was the first such Carnegie library in Brooklyn.

One Hanson dominates the north end of 4th Avenue. The empty lot at left was occupied by the Church of the Redeemer from 1866 to 2016, a total of 150 years. It was considered so important that when the BMT Subway was built below 4th Avenue in 1915, the church merited its very own mosaic sign, which remains in place, mocking the developers who knocked down the church.

Looking northeast at 4th Avenue and Atlantic. The center is dominated by new 2000s Atlantic Center shopping center buildings and by the latest LIRR Flatbush Avenue terminal, which opened in 2009. Art Hunecke has some fascinating photos of the 1907 terminal in its last days.

In the foreground is the 1908 subway headhouse which represented the furthest penetration of the original IRT Subway. It’s had some trials and tribulations over the decades, including stints where it was covered by advertising and temporary restaurant signage. It was restored in the 1990s, but today functions as a glorified skylight.

Despite all the changes that have come to this part of Brooklyn, this street vent, a Giraffe (CHIME-4904) has hung in there masterfully. It has received a relatively recent green paint job, too.

For decades the triangular space between Flatbush and Lafayette Avenues and Ashland Place was an open space occupied at times by a farmer’s market, but Apple Computer has just opened a new store here that is opening the day I write this, December 2, 2017. Among its features are noise dampeners and a grove of indoor potted ficus trees. Is Apple oversaturating the market with computer stores? I recall when the original one in Soho, at Prince and Greene in a decommissioned post office, was a wonderworld and I’d go over there even when it was closed and press my nose against the glass and look at the merch. (These days I usually go to the one on 9th Avenue and West 14th if I need something looked at, since Tekserve’s landlord forced them out of business.) This building will also host a Whole Foods branch.

Also occupying the plot is a new residential tower, 300 Ashland, that is quite narrow on its Lafayette Avenue side but wide on Flatbush. The builders have retained a public plaza at the corner of Flatbush and Lafayette. The developer is Two Trees, which has converted much of DUMBO from industrial to residential. Rents are similar to 461 Dean, above, so only white collars need apply.

I passed a pair of older buildings on the west side of Flatbush between State and Schermerhorn, home to a Department of Social Services office. I was amazed to find them covered with blackboard chalk-style art. It turns out that the buildings have been decorated, until they are demolished, by artist Katie Merz before the entire stretch along Flatbush and Schermerhorn, including a Civil War-era building at Schermerhorn and 3rd, are redeveloped into a complex featuring two schools, a cultural institution, office space, retail, and 900 mixed-income apartments. Some low-rise buildings at Flatbush and Schermerhorn will be knocked down to make room for a pair of residential towers, once of which will be 75 stories high. The whole shebang will be finished in 2025, which still sounds like a science fiction date to me, but is a mere 8 years to go as of this writing.

Temple Square is the forgotten name of the intersection formed by Flatbush, 3rd and Lafayette Avenues. Its namesake, the Baptist Temple constructed in 1917, is about to be absolutely dwarfed by the new #80 Flatbush complex.

The present Baptist Temple sanctuary (1918) has been host to many famous preachers, and contains windows made by Colonial Art Glass of Brooklyn from sketches by Corwyn Knapp Linson. Edward Morris Bowman, a founder of the American Guild of Organists, established the largest volunteer choir in turn-of-the century America, of which Alexandre Guilmant was an honorary member.

On the evening of July 7, 2010, a devastating three-alarm fire caused serious damage to the church interior and organ. NYC American Guild of Organists

The Pioneer Warehouses dominate Flatbush Avenue where it intersects with Livingston Street.

The late Christopher Gray cited Pioneer in the NYTimes in 1988:

Established in 1896, the Pioneer Warehouse Company was an outgrowth of a family auction business initiated on Fulton Street 16 years earlier by Samuel Firuski. Choosing the name Pioneer to reflect what he perceived to be his position in the industry, Firuski acquired a parcel for his warehouse on a triangular block bounded by Flatbush Avenue, Rockwell Place and Fulton Street.

It was a strategic location. The elevated ran down Flatbush Avenue and the Long Island Rail Road was moving to build a new terminal a block south at Flatbush and Fourth Avenue.

The Pioneer is now home to podcasting company Gimlet Media.

Et Tu, Brute? The intersection of Flatbush Avenue and Fulton Street, once called Fox Square (for the vanished Fox Theater) is home to three distinctive buildings, two of them of a decidedly Brutalist frame of mind, the other one from a time of kinder, gentler designs. The first is 395 Flatbush Avenue Extension, constructed in 1974, a black-clad, beetling structure home to various offices as well as retail and a McDonalds.

The Ministry of Love, actually Consolidated Edison headquarters, stands in a triangle formed by Nevins, Livingston and Flatbush Avenue. This is Brutalist at its worst, from the dark and distant time that was early 1970s building design.

[images of Brutalist buildings]

That building replaced the Fox Theatre Building, constructed in 1926 and named for enterpreneur William Fox. Toward the end of its run on Flatbush Avenue in the mid to late 1960s, WINS DJ Murray the K brought package rock and roll tours to the Fox. The Who and Cream made their NYC concert debuts at Murray the K shows. The theatre came down in 1971, to be replaced by Con Ed headquarters.

Across Nevins and Flatbush from the Ministry of Love is #2-4 Nevins.

While the banded-masonry building with the large arched entrance at the SE corner of Flatbush and Nevins Street is impressive as is, albeit giving an aura of faded glory, it was once a great deal more showy — the tower, now cut back to just 7 stories, was once 17 stories/225 feet tall and boasted a clock tower! It was built in 1893 by men’s clothier Smith, Gray and Co. to replace an earlier 1888 clock tower that had fallen onto the Fulton Street el.

Smith, Gray went bankrupt in 1914 and the building has been home to mixed uses ever since then; pawnshops, pool halls and cafeterias have occupied the first and second floors. The clock tower was demolished in the 1940s and the building was cut back to its present 7-story height, and the shortened tower is now nearly vacant.

Christopher Gray: “It is, like the Roman Colosseum in Lord Byron’s play Manfred, ‘a noble wreck in ruinous perfection.’ ” A cast-iron Smith, Gray building on Brooklyn’s Broadway in Williamsburg has been landmarked but not this one.

In addition, a couple of doors down there was a gorgeous Tudor at #16 Nevins, also home to a stone chimney with a playful terra cotta cat sculpture. It disappeared in 2017 and in its place will be a rather bland-looking 28-story residential tower. You can see the Tudor on FNY’s Nevins Street page from 2009.

Prior to 1909, Flatbush Avenue did not extend north of Fulton Street. That year, both the Manhattan Bridge and the Flatbush Avenue Extension, its Brooklyn approach road, were opened. House numbering for the “FAE” begins at the Brooklyn end of the bridge at Nassau Street and extends to Fulton, where Flatbush Avenue begins at #1. It’s interesting how NYC has handled the nomenclature for street extensions; in Manhattan, 7th Avenue was extended south in 1914, with the “new” section called 7th Avenue South, with its own house numbers; 7th Avenue proper begins at Greenwich Avenue. Meanwhile, 6th Avenue was also extended south beginning in the mid-1920s, but the entire avenue is named 6th beginning at Church and Franklin. The city must have renumbered 6th Avenue all the way to Central Park.

Here we see the new collection of high rise apartment tires and offices that are springing up along the FAE corridor.

Heading west along Fulton Street, which has been the Fulton Mall since 1979, when when a lane of traffic was eliminated, an Albee Square Mall building was built on the site of the old Albee Theater, and unique lighting, huge bus shelters, and street signage was installed. However, the Fulton Mall isn’t a “true” mall, as auto traffic and buses still run on it and pedestrians have to stick to the sidewalks.

Most of the housing stock on Fulton Street in the stretch between Adams Street and Flatbush Avenue has remained in place, though, including these Italianate buildings that go back to the Reconstruction era just after the Civil War. In most buildings, though, the upper floors are untenanted.

The V formed by Fulton Street and DeKalb Avenue for most of the 20th Century was dominated by the RKO Albee Theatre (I remember its black marquee with white letters) and the domed Classical-style Dime Savings Bank. In 1979 the theater was replaced by the Albee Square Mall, pictured at left; I still have the 45 RPM record “Turning Japanese” I purchased there.

The V formed by Fulton Street and DeKalb Avenue for most of the 20th Century was dominated by the RKO Albee Theatre (I remember its black marquee with white letters) and the domed Classical-style Dime Savings Bank. In 1979 the theater was replaced by the Albee Square Mall, pictured at left; I still have the 45 RPM record “Turning Japanese” I purchased there.

Today, the City Point residential and retail complex dominates the scene, with its DeKalb Market food hall.

If you think the Dime Savings Bank’s marble exterior, with its reliefs of the Brooklyn Bridge and Roman god Mercury and its numerous Ionic columns, is impressive, wait till you get inside. A towering, gilded rotunda arises under the dome, surrounded by Corinthian columns topped by giant dimes (Liberty dimes, that is; the building was completed by the firm of Mowbray and Uffinger in 1908 and expanded by Halsey, McCormack and Helmer in 1932, fresh from building the Williamsburg(h) Bank Building). A number of banks have occupied the site since the Dime was absorbed by Washington Mutual in 2002; it’s presently a Chase.

Sales encouragement, Bond and Fulton Streets

Has there been a franks-and juice joint at 472 Fulton Street and Elm Place for decades? It seems like it, though this retro sign has only been in place since 2013. Elm Place is one of three surviving one-block streets between Livingston and Fulton, the other two being Gallatin and Hanover Places.

The Liebmann Brothers building on Fulton and Hoyt (opposite the Offerman Building, below) was built in 1888 by W. H. Beers. It’s crowned by a cupola and six terra cotta urns (one has been lost). Beers wouldn’t recognize the exterior now.

The midday shadows did a number on the extravagant Offerman Building at Fulton and Hoyt but you get the general idea. This terra cotta extravaganza, dating to 1890 (the date is featured on the building’s exterior) has been known both as the Wechsler Brothers Block and the Offerman Building. It’s reminiscent of H.H. Richardson‘s Romanesque offerings of the late 1800s, some architecture experts say. Remember, the Fulton Street El rumbled past till 1940, so the upper-floor detail was easily visible then. It makes an impressive sight when viewed on Hoyt Street from the south.

This impressive wraparound building on Fulton and Lawrence once had its own name, as witness the interlocking letters on its facade. The store was once known as Oppenheim Collins, hence the letters OC. Till the late 1970s, E.J. Korvettes occupied the ground floor. In 1979, I bought Pink Floyd’s The Wall LP at that Korvette’s.

I’ve known about this Blimpie at Willoughby and Pearl for quite awhile now. What I hadn’t paid attention to is the marvelous 1931 Art Deco palace, 395 Pearl, which fronts on both Fulton and Willoughby. It is otherwise occupied by medical offices.

Type B park lamps are used to illuminate Pearl, and this one is used to hang a pair of street signs, an unusual combination.

Willoughby Street, a name that has three consecutive silent letters, runs from Adams Street east to St. Edwards Street at Fort Greene Park. When it resumes on the other side of the park, it’s an Avenue and runs east and northeast all the way into Ridgewood, Queens. It is named for Samuel Willoughby, an early-19th Century businessman who founded the Brooklyn Bank. In the background we see the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, which memorializes Revolutionary War soldiers imprisoned and killed in horrific conditions in Wallabout Bay.

It’s amazing how in so many photos I catch yellow lights, which only come on for a second or two.

The lampposts seen here are called Flatbush Avenue poles, as they were first installed on the Flatbush Avenue Extension in 1988. 8th Avenue in Manhattan was also an early convert.

Though 345 Adams fronts on Willoughby it nonetheless has an Adams Street address. It was constructed in the mid-1920s as a private office building. NYC acquired the 13-story building in 1989. Tenants include the Department of Finance, the Department of Probation, the Board of Elections, the Administration for Children’s Services and various other agencies.

Willoughby Street between Adams and Pearl has been a pedestrian plaza for about a decade. Restaurants such as Hill Country Barbecue and Panera occupy the ground floor. If I were still going to school or working in the area, as I was between 1975 and 1981, this would be a frequent visit for me in addition to the Court and Montague Street places I had lunch in then.

Seen here from Adams Street, The US Post Office dominates Cadman Plaza. The Romanesque Revival building dates back all the way to 1885. Much of the post office operations decamped to the Brooklyn-Queens border in the 1990s, but the magnificent building remains as the Downtown Brooklyn Station.

Downtown Brooklyn’s aspect utterly changed, and Fulton Street lost much of its old personality, when entire blocks just east of it were razed between 1950 and 1960 to make way for Samuel Parkes Cadman Plaza, which served to add a lot of green to downtown Brooklyn, which was, admittedly, needed. (The Fulton El had already come down in the early 1940s).

Samuel Parkes Cadman (1864-1936) was a Methodist minister and leader of the Central Congregational Church in Brooklyn from 1901 till his death. It was Rev. Cadman who called the the Woolworth Building in Manhattan the “Cathedral of Commerce.” Cadman Plaza provides views of the Manhattan Bridge from the steps of Borough Hall and allows a vista looking toward the beautiful US Post Office Building on Tillary Street, which was much harder to see before the blocks had been cleared out. Perhaps inspired by Cadman Plaza, Boston scuttled its old seedy Scollay Square in favor of the new Government Center in the early 1960s. However, there’s a kind of forced stillness about Cadman Plaza; it just seems like a plot of green that has been plopped into a neighborhood that didn’t really ask for it.

The construction of Cadman Plaza caused Fulton Street to be renamed as Cadman Plaza West from the ferry landing to Court and Montague Streets. Washington Street, on the eastern end, was renamed Cadman Plaza East. In addition, Adams Street and Boerum Place gained several lanes between Atlantic Avenue and Tillary Street and gained the moniker Brooklyn Bridge Boulevard, which exactly no one uses.

Adams Street’s Flatbush Avenue posts have been outfitted with new LED Bell fixtures, which I call the Abe Lincolns because of their resemblance to the 16th President’s signature stovepipe hats.

Time to enter the Brooklyn Bridge pedestrian/bike path. When Adams Street was reconstructed in the 1950s it became the main entranceway to the Brooklyn Bridge, hence its unofficial title. The Manhattan Bridge looms up ahead. There is also an entrance via steps on Cadman Plaza East.

This is one of a number of fairly anonymous office towers along Sands Street east of the Brooklyn Bridge approach, though an interesting aspect is the presence of two skywalks connecting them. My intention here is to show some remaining Whitestone Bridge T-shaped poles, that used to be ubiquitous on NYC expressways and parkways. They’re only seen now in a few instances such as here, on access roads on either side of the Brooklyn Bridge in Brooklyn and Manhattan.

I am crossing the Brooklyn Bridge for the first time since 2008 when I led a Forgotten NY tour across both the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges on a beautiful June day. The tour did quite well, attracting about 40 fans. At the end of the tour I met two cousins from out of town, John Cornejo (LA) and Moya Whelan (Vancouver) and we spent several hours at the Patriot on Chambers Street before heading out to Cousin Jim’s house in New Hyde Park.

I would not take a Tour across the Bridge at present. The lane is forced to accommodate both pedestrians and bikes, and bicyclists have gotten much more aggressive of late. In addition, the pedestrian side is occasionally dominated by peddlers and idling police scooters.

Visible here are two buildings that did not exist in 2008, #1 World Trade Center, opened in 2013, and the undulating exterior of New York by Gehry at #8 Spruce Street. I hadn’t been much of a fan of Gehry’s stuff — to me his buildings look like crumpled notepaper — but I like what he did here in NYC, a city he has mostly avoided till now.

I can’t say with certainty if the original lightposts on the Brooklyn Bridge resembled the present ones. The current design harkens back to the gaslight era, with footrests for snuffing or lighting gas fixtures. If the original Brooklyn Bridge, finished just as the Edisonian era was dawning, had walkway lamps at all, they were most likely gaslamps. The present stanchions replaced the previous generation in 1982; those older lamps were lit by ‘gumball’ lumes lit by incandescent bulbs. They closely resembled the present ones, but with “busier” molding at their bases.

The Brooklyn Bridge, constructed between 1870 and 1883 by John Roebling (who perished from tetanus during the construction) and his son, Washington Roebling (who suffered from the bends and supervised construction from his home in Brooklyn Heights, relaying commands via his wife) is perhaps the most storied and most famous bridge in the world. I won’t recount the details of its construction here — I’ll let Steve Anderson do it in NYCRoads; Ken Burns on PBS, or David McCullough in The Great Bridge.

The Brooklyn Bridge connects the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn by spanning the East River. With a main span of 1,595.5 feet, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world from its opening until 1903, and the first steel-wire suspension bridge.

Among the Brooklyn Bridge’s drawing cards are its diagonal suspension cables, unique in NYC until a spate of cable-stayed bridges began appearing a few years ago, and its masonry towers with ogee-shaped openings. The earlier John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge in Cincinnati, Ohio, closely resembles the Brooklyn Bridge and could be thought of as a dry run for the much more massive Brooklyn.

There are a plethora of historic plaques on the Brooklyn Bridge, some dating back to its opening and others relatively new. Back in the 1980s and before that, the wood walkway got around the masonry towers on steps, but as bicyclists began to frequently commute on the bridge, those steps were replaced by ramps.

A look south along Furman Street, with the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in the distance. The former Jehovah’s Witnesses Watchtower complex can be seen at left. The structure crossing Furman is the Squibb Pedestrian Bridge, which recently reopened after it had to be closed because it was swaying too much.

Looking south again toward the 1886 Statue of Liberty and the 1932 Bayonne Bridge to its left. The other structures are cargo cranes on the New Jersey shore.

The Bridge is not immune from graffiti that has to be scrubbed off from time to time. The “no locks” sign is there because it became a tradition for people to place Master locks on the cables to profess love and affection. Unfortunately all that metal adds weight to the Bridge and risks destabilizing it, hence their removal. The Bridge’s cables and other aspects are constantly checked for safety. Shortly after the Bridge opened in 1883, a rumor spread like wildfire among bridge walkers that it was collapsing and the resulting stampede caused over a dozen deaths. No such collapse was happening, of course.

A look at the eastbound trafficway. Before 1944, the Bridge accommodated both trolley lines and elevated lines! As Brooklyn’s and Manhattan’s els gradually went out of business, they ceased to cross the Bridge and their space was given over to automobiles. Trolleys left the Bridge in 1950.

The Brutalist Murray Bergtraum High School on Madison Street and Avenue of the Finest. This is a Google Street View desert, likely because of the nearby NYPD headquarters. Fear not, FNY has you covered.

A pair of 1970s-era signs pointing toward both Hudson River tunnels. Getting to both tunnels through traffic-choked local streets from here is a tall order. I like the graphic representation of a tunnel.

This walk was on a weekday. Time to go home in order to beat those rush hour LIRR fares. I got on the #6 train at Brooklyn Bridge, which has only a small bit of its original terra cotta appointments. Then I changed for the #7 at Grand Central, and then the LIRR at Woodside. Home again…

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

12/3/17

11 comments

My 2015 book, From a Nickel to a Token (Fordham University Press), devotes its entire Chapter 5 to the events in 1944 and 1950 that led to the elimination of rail mass transit across the Brooklyn Bridge. In March 1944 the elevated train tracks and the Manhattan terminal building at Park Row were eliminated. Brooklyn Bridge trolleys continued to operate to and from the Smith Street, Vanderbilt-McDonald, Flushing, Graham, and Seventh Avenue lines, shifting to the old elevated tracks, thus creating two parallel lanes for motor traffic. Exactly six years later, in March 1950, the bridge trolleys themselves were eliminated and were soon replaced on the Brooklyn side with buses or trolley coaches. The five bus routes listed issued free paper transfers to the IND A train at High Street, to enable riders who opted for surface routes to reach Lower Manhattan for one fare. This transfer was eliminated in the 1980s but since 1997 has been restored with the citywide Metrocard transfer privileges.

Those Hot dog stands were on several corners in Downtown Brooklyn for many many years..I thought there were none left in Brooklyn…..I remember that Triangle Sporting goods store well…As always, your photos are the best….Thank You

The practice of leaving locks on bridges did not begin with the Brooklyn Bridge. It began in France but is pretty much worldwide now.

I don’t recall saying the the practice began with the Brooklyn Bridge.

Kevin,

Once again, thanks for your excellent photos and historic commentary, perceptive insights, wit and humor.

And for showing me “the old neighborhood(s)” that my grandparents would not recognize today!

Keep up the outstanding work,

Renée

in Tucson

(a former New Yorker)

Great post, as always! Quick note on the Barclay’s Center: the exterior cladding is Cor-Ten (or corten, the generic of the brand name) which is a weathering steel. The rusty patina is real (although usually pre-weathered before installation) and actually protects the steel from further corrosion. It is rather popular at the moment.

For those who don’t know the building that is being constructed and shown to the left of the Manhattan Bridge, that is One Manhattan Square, though I could never understand how that was approved to be built in a such neighborhood with all those housing projects there.

That backward-forward “BB” at the Brooklyn Bridge IRT station always amuses me. Just a nice, quirky little touch that would never pass muster today. Hyper-sensitive newbies would be Tweeting pics of how the backward-B violates their rights under the ADA or some such nonsense. Man, I miss the old New York sometimes…

thank you

Since we are in Downtown Brooklyn… does anyone but me remember the delicious vanilla custard you ate with a long spoon from the snack bar just under the wooden escalator in the basement of the nearby A&S Department Store (circa 1965)?

I am a native New Yorker and happened to stumble upon this blog. Although I’ve been keenly aware of all the places and buildings that you’ve discussed all I have to say is, “WOW! I love this!” Thank you for your presentation!