By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

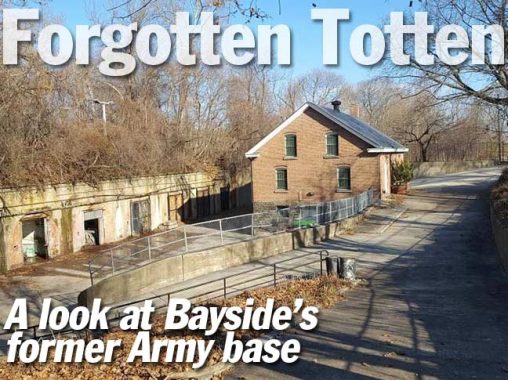

The northeast tip of Queens was once known as Willets Point after the family that purchased this peninsula in 1829. It was acquired by the army in 1857 with the purpose of protecting the city’s waterways from a foreign invasion. Capt. Robert E. Lee drew up the initial plans, which were then modified by the fort’s namesake, Chief Engineer Joseph G. Totten.

Most of this former 150-acre base has been a public park since 2005, with the rest of the base divided between the Coast Guard, Fire Department, Police Department, and U. S. Army Reserve. I was “deployed” to Fort Totten in 2015, to organize the agency’s book collection and drafting historical signs. It was a scenic assignment where I could spend my lunch break exploring the fort and swimming in its pool while basking in the history all around me. The entrance to Fort Totten is an ideal start for a tour. Atop the granite gateposts are balls that were either buoys or torpedo mines manufactured at this base during the Spanish-American War.

Looking towards the East River from the Coast Guard station one sees Throgs Neck Bridge and the Beechhurst neighborhood behind it. Under the bridge approach is the former Wildflower estate and to its left is Little Bay, whose crescent shoreline hints at a proposed beach that was never built. See the essay on Whitestone’s Far North for more details on this area.

Along with public agencies, some of the buildings on the former base are leased to community nonprofits. The former Officers Club is the proud home Bayside Historical Society. Completed in 1887 this “castle” initially served as the Officers’ Mess Hall and Club for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers School of Application. Although the USACE relocated to Washington in 1902, the building’s outline appears as the logo of this agency.

Continuing further on Sgt. Charles M. Beers Avenue, we see the fort’s oldest and most neglected structure, the only building on the base that predates the military. The Willet Farmhouse was built in 1829 shortly after Charles Willet purchased the peninsula. The Army abandoned this house in 1974 and despite city landmark designation, it continues to rot away. For years the sign outside this fenced-off home had the words, “Please Excuse My Appearance, I am a Candidate for Historical Preservation.”

The Willett family has a long history in this region, as far back as 1643 when Richard Willetts was among the founders of Hempstead. The Parks sign for Willets Point Playground in nearby Whitestone tells the full story. The house overlooks the former ice pond, one of two ponds at Fort Totten. The pond is located within the army enclave, so it’s not accessible to the public. As for Sgt. Beer, according to the Paul Thomsen, archivist for the Society for Military History, he managed the arms depot at Fort Totten in the late 19th century. Forgotten-NY has a detailed list of NYC streets that carry full names of individuals.

Every military base is like a small town and Fort Totten is no exception. It had a chapel, theater, and a YMCA that was built in 1926. This neo-Georgian building remains vacant but in 2012 Will Ellis of Abandoned NYC snuck inside to take photos.

Fort Totten’s theater building has also seen better days. In its early years, servicemen had to follow the dress code to gain admittance to this theater. Both the YMCA and theater buildings have historical signs with photos that tell their stories.

As Kevin noted in Oct. 2018, the base has its own set of streets with unique signs and lampposts. The FDNY has since painted over some of the names on the sign plates for their own reasons. The homes at Fort Totten never had street addresses, they always had numerical designations such as Building 107 or Building 203. So in reality, the street names are useless for postage and directions. Across from the theater, Red Cross Lane is marked with a sign on a building wall, a rarity in this city.

With the exception of the batteries, Willets Farmhouse, and Ernie Pyle USAR Center, most of the buildings on the base are Romanesque Revival. The 1999 Designation Report by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission has the full details on every building at the base.

As with all military bases, Fort Totten has a Parade Ground that was used for muster. Within this field is the public pool and behind it, three former barracks, two of which are crumbling. Governors Island also has a pool of similar size but the city opted to leave it abandoned while restoring that base’s theater building.

The Commanding Officer’s House, also known as Building 422 was completed in 1908 and serves at the headquarters of the northeast Queens region of NYC Parks. It certainly commands attention with a view of the Parade Ground at its center.

The actual fortifications can be seen at the northern tip of the peninsula, which also has the park’s highest point at 68 feet. From here one can see the East River widening into the Long Island Sound. It is a very windy corner of Queens.

The visitor’s center has a modest display of historical memorabilia and mannequins in uniform. From here, Urban Park Rangers start their tours that lead into the tunnels and onto the ramparts of the fort. There is a myth at Fort Totten is linked by a tunnel to Fort Schuyler on the opposite side of the East River. As I see it, the only tunnels here are those connecting the batteries within Fort Totten. Among the names and slogans scrawled into the tunnel wall connecting the ordinance yard and Water Battery is “Remember the Maine.”

I did not have time to take a tour of the actual fort, so here’s a Cold War period photo from Little Neck resident C. Manley DeBevoise, found in the NYPL Collection. Construction on this battery stopped in 1862 when it became clear that its design was obsolete and the high improbability of a Confederate assault. From that point on, the base was used for arms storage and training rather than actual defense of New York’s waterways. The fort was renamed after Totten in 1864, following his death. Born one year before George Washington was sworn in as President, Totten served this country in the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Civil War. One day before his death he was awarded the title Brevet Major General.

Above the Water Battery are the Endicott batteries that were built in the last decade of the 19th century. But the Spanish and German invasions never came. These batteries were abandoned in 1938. The field facing these batteries was planted prior to 2005, when a dozen unremarkable residences were demolished in favor of more open space.

Designed by landscape architect Nancy Owens, this “park inside a park” features a hilly lawn, mounds covering up the ruins of King Battery, a playground, wetland, and picnic area.

Charles Willets died in 1832 and was buried in a family plot on his property. Although his body was reinterred at Green-Wood Cemetery in 1855, this stone marker stands on the gravesites of the farm’s previous owners, the Thorne-Wilkins family, which claimed this property in 1645.

Leaving Fort Totten, one can rest on the beach or walk the jetty in Little Bay Park. Along the shore is a bike path that terminates at this park. This path is part of the Brooklyn-Queens Greenway, a 40-mile bike route that begins in Little Bay Park and ends on the Coney Island Boardwalk. Along the way, it runs through 13 parks, two botanical gardens, the New York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Museum, the New York Hall of Science, two environmental education centers, and four lakes. Arguably the city’s version of the Appalachian Trail as most of it runs through parkland rather than streets.

For more details on the history of Fort Totten, check out the historical timeline at FortTotten.org.

Forgotten-NY has been to most of the city’s historical forts, including Fort Tilden, Fort Schuyler, Fort George, Fort Hill, Fort Clinton, Fort Defiance, Fort Independence, Fort Tryon, Fort Greene, Fort Hamilton, and Castle Clinton. That’s a lot of forts since Kevin began his service to this city in 1999. Seriously, he’s been to quite a lot of former military bases considering that he never actually served in the military.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

12/28/18