Continuing my Manhattan cross streets series. I’ve done them piecemeal in the past, but I’ve already posted 20th Street, 22nd Street, 17th Street and 10th Street in this batch, and 14th Street as well in autumn 2019 with more to follow. Before the Great Infection, I spent a number of Saturdays (and some Sundays too) crisscrossing Manhattan via its numbered streets. Over the years, I’ve done this quite a few times and I was amazed at how much stuff I missed and how much material I knew about and posted here and there, but never really formalized or categorized. Eventually I might make these “crosstown” posts their own separate category.

A word about the Great Infection. For the first time since mid-March, I’m about ready to use the LIRR to get to Woodside to explore western Queens, and occasionally I get rides to other parts of Queens, but I’m not yet ready to take the subway. In any case I bought a used Panasonic Lumix and I can’t get it to focus on zoom, and till either of those problems are resolved my usual wanderings in which I take hundreds of photos will be curtailed…

I walked 18th Street from east (1st Avenue at Stuyvesant Town) to west: 8th Avenue. I’ll leave the 4 blocks between 8th and 11th Avenues for another time and add them on when I have the photos.

Stuyvesant Town sits on an almost-square defined by East 14th and East 20th Street, 1st Avenue and Avenue C, with 89 buildings containing 8,757 apartments. By auto it’s accessed by a series of ovals located on its four border streets, and pedestrians can easily access its four “quadrants” via the center oval. A second residential complex, Peter Cooper Village, sits north of East 20th Street.

I have a personal connection to Stuyvesant Town — my father worked here as a custodian for 30 years, between 1958 and 1988; he only retired when he turned 70. This was an era in which unionized jobs with ample benefits were … somewhat more attainable than now. He would work the usual Monday through Friday, but occasionally he would work the weekend and take Wednesday and Friday off, on which days he would see me off to school. It was a long way with two trains from Bay Ridge to Stuyvesant Town, so he would leave the house at around 7 AM or even before that, before I got up, usually arriving home around 7 PM. During snowstorms he would need to go in at off hours to shovel snow.

What’s surprising is that I never visited Stuy-Town when he was working there (I do recall heading over there an evening or two by car when one of my father’s friends drove us there). The old man never helped put me on the famed list of people waiting for apartments to open up, but as he’d probably say now if he was still around, “You didn’t ask me!”

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”1″]

(Using a new WordPress Photo Gallery plugin, which won’t align the galleries on the left, hence the somewhat wonky appearance. I’m trying to get NextGen, my usual plugin, working again. As always, clicking on an image will bring it up full size.)

326-328-330 East 18th Street, Italianate brick row houses set way back from the street with actual front yards and castiron verandas, provide a contrast to the other apartment buildings on the block. These buildings were constructed in 1853 and were likely the first buildings completed when 18th Street itself was built. The trio are protected by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

318 East 18th, owned by Joel Krupnik and Muriel Castellanos (their names are on a plaque on the second floor) have decorated their townhouse with weird masks and sculptures. In the past, Krupnik has displayed “a bloody St. Nick holding a knife in one hand and a severed head of a doll in the other” according to the New York Post.

A few doors down is #312, where James W. Blake wrote “The Sidewalks of New York” in 1894.

Well into the 20th Century it was common practice for women to give birth at home, assisted by their husbands, “significant others” and one or more midwives. The practice shifted to giving birth in hospitals as medical techniques improved in the early part of the last century. But as early as the 18th Century, trends started shifting away from giving birth at home. In 1798, there was a yellow fever epidemic in New York City and a prominent physician, Dr. David Hosack, founded the first Lying-In Hospital (an early name for a maternity ward) for widows of yellow fever victims. Hosack is an undeservedly forgotten name in history annals; he founded Bellevue Hospital and attended Alexander Hamilton after his duel with Aaron Burr in Weehawken, NJ in July 1804.

The Rutherford Medical building, 2nd Avenue between East 17th and 18th Street, is a magnificent edifice designed by R. H. Robertson in 1902, replacing the mansion of Hamilton Fish, a prominent NYC politician. The facility was founded in 1898 with a grant from financier J. Pierpont Morgan in 1897 for the Society of the Lying-In Hospital of New York.

The new Lying-In Hospital opened in January 1902 and featured state of the art operating rooms (think of the recent cable TV series “The Knick”) along with lecture rooms, a solarium and even a museum. In that era sunshine was thought of as having essential recuperative attributes, so rooms were bright and sunny. It was considered the best maternity hospital of its era. It served rich, poor and in between, and more than 50,000 children were born here every year.

Rutherford Medical, as it was called, after nearby Rutherford Place, became the Manhattan General Hospital from 1936-1957, continuing maternity services. After stints as a methadone clinic and Beth Israel Medical Center, it was sold for $8M in 1981 and is, what else, condominiums today.

The old tradition of Rutherford Medical is evident today on the exterior, which has bas-reliefs of young children.

An urban contrast, brick townhouses on East 18th between 2nd and 3rd Avenues in the foreground, with the high rise, #201 East 17th (Park Towers), in the back. These buildings are on the northern edge of the Stuyvesant Square Historic District, which includes Stuyvesant Square itself, both sides of 2nd Avenue between East 15th and 17th Streets; much of East 15-17th between 2nd and 3rd Avenues; and the south side of East 18th between 2nd and 3rd.

This row of buildings was constructed between 1849 and 1857.

Continuing west along East 18th between 3rd Avenue and Irving Place. This group of townhouses, #133-153, is on the southern edge of the Gramercy Park Historic District. Most are Anglo-Italianate buildings constructed from 1851-1853. They were renovated in the 1920s but not enough to strip away moat of their original elements.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”2″]

A second grouping of 1850s classics on East 18th, part of the Gramercy Park landmarked district.

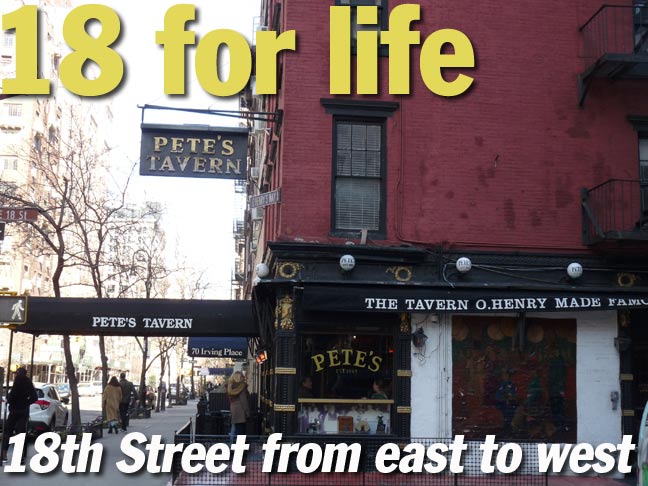

There are a number of taverns in NYC jostling and vying for the title of the city’s oldest bar. McSorley’s, on East 7th and Cooper Square, claims the title. But there’s also the Bridge Cafe in the Seaport neighborhood (though Hurricane Sandy seems to have shut it down permanently). Pete’s Tavern, East 18th at Irving Place, has also joined the battle. It’s all a matter of semantics, as Pete’s is billed as ‘New York’s Oldest Original Bar.’

The building it occupies was built in 1829 and featured a grocery (in previous centuries liquor was sold and consumed in groceries) by 1851, with a more specific saloon called Healy’s in place by 1864. It was operated as a flower shop hiding a speakeasy during Prohibition days, after which Peter “Pete” Belles purchased it, giving the place the famed name. Since the 1950s, an Italian menu has been featured, though traditional bar food like burgers (excellent in quality) and steaks are sold too. The building itself is 5 stories high with, I’d imagine, apartments on the upper floors (I’d enjoy living above Pete’s) and a lengthy one-story rear that may have contained a bowling alley at one time.

Pete’s is closed for the duration of the Covid Crisis.

Before and after Prohibition Pete’s was frequented by literary types such as William Sydney “O. Henry” Porter (as in the old Lion’s Head and White Horse Taverns in Greenwich Village).

As far as I know, this is the only Twin bishop crook lamppost in NYC, at the SE corner of Irving Place and West 18th Street. In the early 20th Century cast iron era, there was a specialized Twin post made to illuminate two sides of a street at once, and Bishop Crooks were never twinned. After the classic lamps’ comeback in the 1980s, Twin versions of the long-armed Corvington posts became commonplace, and there were even new Twins produced (mainly along West 40th and 42nd Streets and 6th Avenue around Bryant Park) and along Central Park West. But this is the only Twin bishop crook.

Paul & Jimmy’s Ristorante, 123 East 18th, has been in existence since 1950 by Paul & Jimmy Delgado, but not always at this address; it was formerly located on Irving Place. In 1968, Cosmo Azzollini purchased the business and the Azzollini family has operated it since. I liked the handlettered wood sign.

I don’t stop into the Old Town Bar as much as I used to but it’s comforting to know it’s there, at least in normal times. I was in more often when I worked in the area, in various jobs in various eras starting in the early 1980s. The last time I was there, I was with a couple of friends, one of whom I have lost touch with and another, lamppost enthusiast from England Alan Dade, has since passed away.

Viermeister’s opened as a Teutonic-themed saloon at 45 East 18th in 1892; Henry Viermeister took over in 1912, and it became the Old Town in 1936.

The interior is still dominated by the same style tile floors, pressed tin ceilings, etched and stained glass, beveled mirrors, brass lighting fixtures, woodworked bar and booths and round-edged tables that were present on opening day. The brass lighting fixtures, as a matter of fact, were originally gaslamps. The leather upholstered booth seats had hidden compartments to store drinks while the cops raided during Prohibition. After that misbegotten government adventure, another German family bought the place and renamed it Old Town. Nonfunctioning buzzers that used to summon servers are still in place at the booths. [me, in my SpliceToday article about the Old Town in 2016]

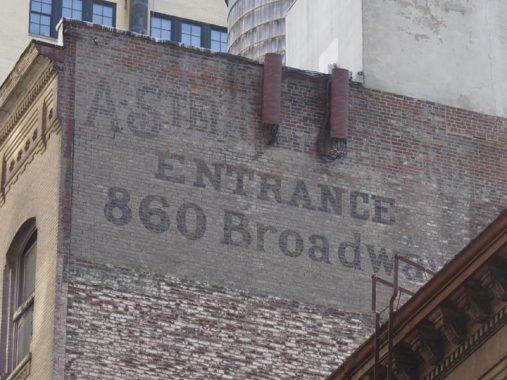

Here’s an ancient painted ad high above #34 East 18th Street; Abraham Steinhardt’s “fancy goods” distributorship was located around the corner on 860 Broadway from 1912-1921, according to the Indispensable Walter Grutchfield. Founder Steinhardt had passed away by then and his son-in-law David Rosenthal was in charge until the company dissolved in 1929.

The Hawes Building, #872 Broadway at East 18th, was constructed in 1847. It has had many different businesses and interests pass through it including the Abraham Bogardus photo studio, where presidents U.S. Grant, James Garfield, Rutherford B. Hayes and Chester A. Arthur, as well as leading 19th Century lights William Cullen Bryant, Jay Gould, Henry Ward Beecher and William H. Vanderbilt had their portraits done. It wasn’t known as the Hawes Building until it was purchased by B.F. Hawes in 1901, who went ahead and named the building for himself, displaying his name at the roofline.

Info from the equally indispensable Daytonian Tom Miller.

Broadway and East 18th are on the edge of yet another Landmarked District, the large Ladies’ Mile Historic District, which roughly runs between East 17th and 24th Streets, and midblock between 6th and 7th Avenues to midblock between Broadway and Park Avenue South; a sliver goes as south as 5th and West 15th.

With Rowland Hussey Macy leading the way in the mid-1850s with a flagship store at Sixth and 14th, and A.T. Stewart’s Cast Iron Palace further south at 9th Street, Sixth Avenue from 9th north to 23rd was lined with big, buxom Beaux-Arts buildings that catered to ladies who lunched and then shopped. In Ladies’ Mile heyday, over a dozen huge emporia lined the avenue…but were thrown into shadow by the Sixth Avenue El until 1939, when the el was razed. After that, the great stores could be seen in all their glory. But the glory would fade rapidly as the years went by; the buildings slowly decayed, and most were in sad shape indeed until, gradually and slowly at first, they began to be restored in the late 1980s. Today, Sixth Avenue is as busy and bustling a shopping street as it ever was.

Here’s the SW corner building at Broadway and East 18th, the Romanesque #867-869 Broadway, which went up in 1883 as the offices of music publisher Oliver Ditson; the building is known as the Ditson Building. In the late 1800s, Union Square was NYC’s entertainment district and home to a number of music publishing offices. Paragon Sporting Goods is the longtime ground floor tenant. Though the company was founded in 1908, it wasn’t there in 1940 as this Municipal Archives photo indicates.

I have become fascinated with grand old firehouses, especially still-active ones such as Engine 14, at #14 East 18th. The firehouse opened in 1894 (the date emblazoned on the facade) and is the work of architects Napoleon LeBrun and Sons, who designed many great firehouses in the same period around town. The fire company itself has been in existence since 1865.

Some great escapes (fire escapes, that is) can be found at #10 East 18th Street. It is actually the rear end of #7 East 17th Street, a Neo-Renaissance building constructed in 1902. I liked the bay window with curving glass panes on the ground floor.

The diminutive #8 East 18th is hammed in by the taller #6 and #10 East 18th; the taller buildings are the rear ends of East 17th Street buildings constructed in 1902. That’s pretty old but #8 is decades older; it went up in 1845, with modifications to the facade over the decades. Health food restaurant Sweetgreen occupies the ground floor.

The 15 story 126-128 5th Avenue at West 18th was about as high as buildings went in 1905 when it went up. It replaced the Hotel Logerot and was home to clothing manufacturing and distributing offices in its early days.

Across 5th Avenue Barnes & Noble shuttered its longtime college and mass market bookstore, a staple for generations of college students, at 105 5th Avenue in 2014. What a messy warren of volumes it was!

The loft building #7-9 West 18th has an interesting pediment above the front door with the house numbers. I have also begun to notice interesting house number treatments that occur especially on older buildings, like this one (1893).

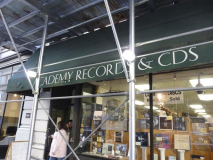

LPs and CDs are still a thing at Academy Records & CDs at #12 West 18th. There are some interesting titles in the window such as The Fall’s Live at the Witch Trials, Toots & The Maytals, a Marvin Gaye box and plenty of Beatles. I still remember giant record emporiums around town like Tower Records, The Wiz, J&R Music World, HMV and even Sounds on East 4th Street. I could enter on a Sunday PM, my usual time after the baseball or football game, and emerge with stacks of wax and not a big dent in my pocket from lost cash. You did have to get your choices analyzed by the checkout crew, though. Academy started as Academy Books in 1977.

At #16 West 18th, Barnes & Noble may be gone but longtime children’s Books of Wonder, a mainstay since 1980, was still hanging in at least until the Covid Crisis began in March 2020.

The Cluett Building, #23 West 18th, is actually the rear end of #22-28 West 19th. It went up in 1905 and was designed by Robert Maynicke, who is seemingly ubiquitous in the area. Shirt manufacturers Cluett, Peabody & Co. were tenants beginning in 1905, hence the name.

Arrow Shirts were produced by the Cluett-Peabody company, which sold both collarless and collared shirts (most notably the Arrow brand); until the 1930s, detachable collars were the norm and were put on separately. The company was instituted in 1851 as Maullin & Blanchard after a series of takeovers and mergers became Cluett, Peabody in 1891. Its flagship headquarters was on River Street in Troy, NY; both my mother and grandmother, who were from Troy, worked in that building in the Fab Forties. The company was acquired in 1985.

Siegel-Cooper, built in 1895, was the largest of the Ladies’ Mile emporia, containing 15.5 acres of floor space. It used to have a clock tower and a large fountain, since removed and placed in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles. Note the large picture window on the 18th Street side: a ramp from the El allowed passengers to walk directly into the store from the platform. It’s presently home to retail such as Bed, Bath and Beyond.

The building itself still has to be seen to be believed: it’s the apotheosis of the Beaux Arts era, with huge frontage on 8th Avenue and West 18th and 19th Streets. On this 18th Street arched entrance you can detect the SC digram. I say “detect” because it’s so intricate that you have to stare at it for awhile to make out the S and the C.

Above is the former B(enjamin) Altman building, used by the firm, founded in 1865, between 1877 and 1906, when it moved to a new store encompassing an entire city block: 5th to Madison and 34th to 35th, until the store closed its doors forever in 1989. That means B. Altman has left behind not one but two of NYC’s most beautiful buildings.

On the SE corner of West 18th at 604-612 6th Avenue is a building developed by David Price and built in 1912; it’s a toned-gown version of the Siegel-Cooper building just to the north. Early tenants included a first story saloon and restaurant, and a loft at the second story. Currently an Old Navy franchise is on the ground floor; previous tenants included a Honda car showroom.

Here’s a group of surviving brick stable buildings on the south side of West 18th between 6th and 7th Avenues, at #126-140. There had been more stable buildings in the area but these are the survivors, and all are under the aegis of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Unfortunately Movie Star News at #134, which sold movie posters, is gone now.

The Hellmuth Building, 154 West 18th, was built in 1906 and converted to co-ops in 1988. Chiefly of interest for me is the terra cotta lettering on two separate entrances. Take a look at that double-L ligature!

The Walker Tower, 212 West 18th off 7th Avenue, was one of many hulking telecommunications Art Deco buildings designed by Ralph Walker (1889-1973) in the 1920s and 1930s. The building now contains very expensive condos.

#237 West 18th has some impressive zig zaggedy brickwork, as well as some gilded monsters on the entrance pediments.

#236 West 18th, now home to a furniture store, was once a warehouse for the massive former Siegel-Cooper emporium facing 6th Avenue between West 18th and 19th in the Ladies’ Mile district from 1896-1917. Before the widespread use of motor trucks, horses and wagons would shuttle goods to the store from here. Note the SC digraph on the facade. You can find another one on West 17th between 8th and 9th Avenues.

B. Schlesinger, #249 West 18th, manufactures uniforms, including familiar ones you see every day for the NYPD, USPS, nurses’ hospital uniforms and much more.

I’ll check the rest of West 18th between 8th and 11th when the Covid nonsense is over. Meanwhile…here’s 19th Street.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

5/31/20

6 comments

Another excellent posting. “18 for Life” is a nice pun for Jewish people. In written Hebrew, one has the option of expressing numbers in the normal Arabic format that the Roman alphabet uses, or expressing numbers using letters of the Hebrew alphabet. It’s similar to the English language option of writing numbers (18 vs. eighteen, for example). The Hebrew equivalent to “18” is the word “Chai” (transliterated), which is also the Hebrew word for life. For that reason, “18” and its multiples (36, 54, 72, 180, etc.) are good luck numbers to Jewish people. One well-known song from the classic Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof is titled “To Life, To Life, L’Chaim,” or almost the same as “18 for Life.”

Great job done on 18th so far. Lookingforward to the look at everything beyond 8th Ave as a former (1991) resident of 350 W. Stay safe & healthy!

Because I was in that line of business, long before I first visited NYC, I8th Street was a destination. That was because 220 W 18th Street housed the venerable N.G. Slater Corp, premier pinback button makers. From the compny history page “Founded in 1936 by Nathaniel George Slater as a specialist in “Lithographed Metal Advertising Buttons and Tabs”, the button business boomed in the 30s and 40s. One of Slater’s first major clients was the federal government, which ordered buttons supporting the National Recovery Act and war bonds. The 1950’s and 1960’s brought space race buttons and civil rights buttons, with the company supplying both the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black Panthers. In 1972, Nathaniel slapped a yellow smiley face on a button, wished the world a happy day, and helped create an icon for a generation.”

That last bit maybe a bit lyrical, but, according to Wikipedia, working with Bernard and Murray Spain of Philadelphia, between 1970 and 1972 Slater made 50 million smiley buttons. I did visit many times in the late 80s, an entire floor filled with button presses that didn’t look to have changed much since the 30s. It was an ILGWU shop. The firm is still operating, but much downsized, on W 38 St.

Although it’s underground and therefore perhaps beyond the scope of this article, the closed IRT station at East 18th Street and Park Avenue South was worth a mention. It is a time capsule of subway operations before 1950. An original 1904 IRT local station, its platforms were lengthened to accommodate 5 cars in about 1910 and remained that way until the day it closed in 1948. While Manhattan above builds, erases and builds again, 18th Street station is frozen in time in 1948.

Hi I live in England, United Kingdom. I am currently researching my ancestors and have found out that my Great Grandfather William Frederick Cooper is on the 1920 Census as a Restaurant Keeper at 11 West 18th Street along with his wife Bridget.

Is there anyone out there who may have a photo of the Restaurant or any details of him and his wife?

Hello – I own an original architectural rendering of the Speigel and Cooper building on 6th between 18th and 19th. Depicting life in NYC with horse & buggies and cable cars. The building has/ had a massive clock tower, and the roof edge was lined with American flags. I would like to donate it to a library.