Once again I have a weekend “off” when I turn things over to Sergey Kadinsky, who is ubiquitous. –Editor

By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten New York correspondent

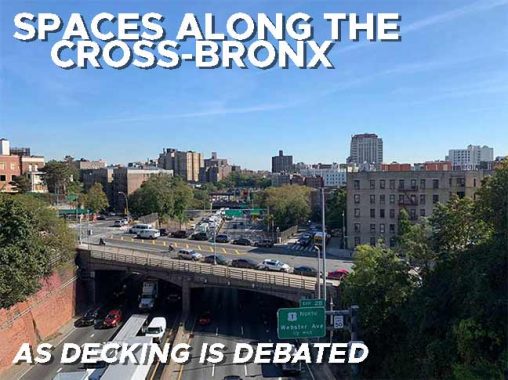

THE Bronx has a history of traumatic disruptions that tore the fabric of its neighborhoods. At the top of the list is the Cross-Bronx Expressway which runs from Throgs Neck to Highbridge through Mount Eden, Crotona, West Farms, Parkchester, and Unionport. Unlike his parkways, where Robert Moses included green shoulder spaces as a buffer between neighborhoods and highways, this expressway has very little green space along its route. There is talk of decking the trench portions of the Cross-Bronx with parkland to reduce pollution and asthma, but until then there are a handful of small parks that were created as a result of spare land that opened up during the condemnation of buildings for the highway’s path.

GOOGLE MAP: SPACES ALONG THE CROSS-BRONX

DeRosa O’Boyle Triangle honors William Anthony DeRosa and Andrew O’Boyle, two Throgs Neck natives who gave their lives for this country during World War II (1939-1945). The triangle predates the highway as it borders East Tremont Avenue, Dewey Avenue, and East 177th Street, which was widened into the expressway. The two avenues cross each other atop the highway, resulting in a wider overpass that has potential for more trees and benches to hide the highway from view. Dewey Avenue honors the commodore of the Spanish-American War who conquered the Philippines, while Tremont Avenue runs the width of the borough from east to west.

Across from this triangle is the Throgs Neck branch of the New York Public Library, built in 1973 in an austere modernist design. Also nearby is P. S. 63, a CBJ Snyder design completed in 1925. Historically the spelling of Throgs Neck had two g’s but I feel that this language is long overdue for a spelling reform.

John McNamara Triangle is named for the lifelong borough resident who walked every street in the Bronx and wrote the book on their names. The triangle was named for McNamara in 1985 by Mayor Ed Koch, and he dutifully added it in the third edition of History in Asphalt: The Origin of Bronx Street and Place Names. Sadly, there are no plaques or monuments for McNamara in this park and that’s why we have Forgotten-NY. He died in 2012 at his home in Throgs Neck.

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

The unnamed .22-acre triangle at Swinton and Philip Avenues could be adopted by a community group and beautified, or at least given a formal name. For now, the only place that you’ll hear about it is here.

Bruckner Playground is located on the north service road, built in 1957 in tandem with Middle School 101, which is co-named for Edward R. Byrne, a police officer killed in 1988 by a drug dealer. A park in Queens also carries his name, along with a street co-naming. This playground and school were built at the same time as the expressway. Its namesake, Henry Bruckner was a Bronx Borough President from 1918 to 1934 and his name appears prominently on a boulevard and expressway that connects Pelham Bay Park to Triboro (RFK) Bridge.

The Cross-Bronx Expressway crosses Westchester Creek in a tangle of ramps that connect it to Hutchinson River Parkway, Whitestone Expressway, and Bruckner Expressway. Between Westchester Creek and Westchester Avenue, the expressway takes the route of East 177th Street, as seen in this aerial survey from 1950. To build the highway, buildings on the north side of the street were demolished in favor of six lanes of traffic and a north service road. The arrangement is similar to Brooklyn’s Meeker Avenue, which already ran through its local street grid and was then widened to accommodate the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

In the Castle Hill neighborhood, Havemeyer Playground is bounded by the highway, Watson Avenue, and Havemeyer Avenue. Its namesake is William F. Havemeyer, who served as the city’s mayor for three terms in the mid-19th century. His brother Frederick established the Domino sugar refinery in Brooklyn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior to the expressway, E. 177th Street ran through the grid. It had a triangle at its intersection with Castle Hill and Haviland avenues. The expressway’s route condemned buildings and intersections on the north side of E. 177th street, resulting in the elimination of this triangle. Castle Hill Avenue was given an overpass across the expressway but Haviland did not. In this 1937 photo looking east on Haviland, we see the iconic Castle Gardens apartments. The triangle and buildings on the right side of this photo were erased by the highway. Today, the spot where this photographer stood would be the south service road looking east.

On the south side of the expressway, Church Triangle is bound by Castle Hill and Watson avenues. Its namesake is the Holy Family Roman Catholic Church across the street but this triangle predates the highway. It was acquired by the city in 1914 when E. 177th Street ran through the east Bronx grid. This park contains a monument honoring 12 local residents who died for the country during World War One.

Crossing back to the north service road, at Ellis and Olmstead avenues is Chief Dennis L. Devlin Park, named for a firefighter killed on 9/11/01. At the time he was assigned to Engine Company 45 in the Bronx. Prior to this renaming, it was Olmstead Triangle, unrelated to the great park planner. Its namesake was the avenue, which honors a landowning family from the 19th century.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hugh J. Grant Circle at Westchester Avenue needs no introduction. Kevin has been here before on his visit to Parkchester, his walk along Westchester Avenue, and much more. As with many streets and parks in eastern Bronx, the namesake was a mayor. On account of this park’s size, the Cross-Bronx Expressway has its longest tunnel under this park. Ironically, Mayor Grant opposed the acquisition of parks on the city’s northern border arguing that they were too far from the public and not worth the cost.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The circle is bisected by the Pelham Bay elevated line, which built a monumental station here in 1920. Initially it was the East 177th Street station and renamed Parkchester after the massive apartment complex was completed. Its namesake was the easternmost extension of the Bronx-Manhattan numbering grid. After the expressway was built, East 177th Street became the south service road for the highway.

Virginia Park and Virginia Playground are across the street from Grant Circle, named for Virginia Avenue and built in tandem with the expressway. The north service road separates these two Virginias. I can imagine the highway trench being decked here, which would expand the size of Virginia Park.

Wood Park has Wood Avenue running on its northern side, named for Mayor Fernando Wood, who previously served in Congress, established an independent political machine, supported immigrants, but his place in history ended in infamy as he was a Copperhead Democrat. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he supported the right of states to secede from the Union. Recognizing the city’s reliance on the cotton trade, he proposed the secession of Manhattan from the country. While the state sent the largest number of volunteers for the Union cause, Wood’s constituents were forgiving of his apparent treachery. He returned to Congress in 1863, where he argued against the abolition of slavery. He remained in office until his death in 1881. I would not be surprised if a renaming comes to this triangle.

|

|

|

|

|

Back to the south service road, at McGraw Avenue and Taylor Avenues is an unnamed .14-acre triangle that has benches. I’m surprised that it has not yet been given a namesake, as each year city lawmakers bestow new names and honorific co-names to streets in each of the 51 Council Districts.

Two blocks to the west is St. Lawrence Triangle, sharing its name with the avenue that crosses the highway by the park. The namesake is a Spanish-born early Christian martyr who distributed alms to the poor and refused to share them with the Roman prefect. For this act of disrespect, he was barbecued to death.

The .12-acre triangle at Rosedale Avenue doesn’t have an official name but it receives many visitors as a stop on the Queens-bound Q44 bus. Running between West Farms and downtown Jamaica through the heart of Flushing, it is one of two bus routes connecting the Bronx and Queens. As a Select Bus Service route, it has stops spaced far apart and tickets are purchased before boarding, similar to a train.

Noble Playground is on the north service road, near the interchange with Bronx River Parkway. This park was completed in 1939 in tandem with the parkway, rather than the expressway that was built two decades later. Noble Avenue follows the park and their likely namesake is Alfred Noble, a city engineer in the 1880s. No relation to the Swedish chemist of the nearly identical name. The neighboring streets, Croes and Fteley Avenues, are also named for men in that profession. A block to the north of the service road is Mansion Avenue, named at a time when the Bronx was less densely populated. Noble Playground marked the western end of the highway’s first phase, which was built between 1948 and 1959. Four years later, the Cross-Bronx Expressway reached across the Harlem River on its way further west. I recently found a sidewalk that follows the parkway for nearly a mile, connecting to Bronx Park.

The expressway crosses the Bronx River at Starlight Park and then continues west in a trench after Boston Road. Inside this park is a concrete pillar in the middle of the Bronx River that represents a ramp that was never completed.

Where Southern Boulevard and its twin Crotona Parkway cross the highway, the city photographer in 1940 identified a lively commercial block: Dorogusker’s dairy and Moe Green’s grocery are among the Jewish shops that were condemned, along with the apartments above them. In 2012, this section of the boulevard was co-named in 2012 for the 65th Infantry Regiment, a Puerto Rican army unit best-known for holding the line against communist forces during the Korean War.

I can imagine a decked highway here and a restored row of small businesses on this block of Southern Boulevard bringing life back to this seam in the neighborhood. A block to the west of this overpass are Trafalgar and Waterloo Places, two short streets named by a surveyor with an interest in Napoleonic wars.

On the east side of Crotona Parkway is a narrow unnamed walkway connecting it to a dead-end on Daly Avenue. In places where there was not enough room for a service road, walkways maintained by the Parks Department were constructed. Two apartment buildings on Crotona Parkway were demolished in favor of the expressway and this walkway.

This alley first appeared on a planning map in 1946 and became reality a decade later. On this map, I circled the condemned grocery store and highlighted the alley. At the time of the highway’s construction it was a dense neighborhood. In the 1970s many people were fleeing the uptick in crime and the buildings were burned by arsonists. To give a better impression of the borough to passing motorists, the city installed fake window panels on the hollowed-out buildings from 1980 to 1986. Two blocks to the north, photographer Camilo Jose Vergara documented the decay and revival of the neighborhood at Vyse Avenue. The imagery is identical to Charlotte Street, the best-known example of the borough’s transformation. Where tenements stood there are now two-story townhouses obscured by sidewalk trees.

If buildings could talk, the two walkups 1892 and 1894 Daly Avenue would have so much to tell. Prior to 1953, they stood on a block of other walkups and tenements. To their left, the McKeon Funeral Home at 1890 Daly was condemned for the highway. The company relocated to Norwood, in business for more than a century. Two decades later, their neighbors to the right and across the street were destroyed by arsonists and demolition crews, later to be replaced by the townhouses.

Fairmount Playground is sandwiched between the highway and Fairmount Place, built in the 1950s. Its name comes from an estate on this site in the 19th century. No play equipment here. It is a paved sitting area with a few trees facing the highway trench. Back in 1960, the park didn’t have a single tree. If the highway were decked here, this park could nearly triple in size! Across the street is Gethsemane Baptist Church with its Gothic-revival windows. When this church was built in 1901, there were homes on both sides of Fairmount Place. The street has a mix of old 6-story apartments and smaller residences built in the 1980s in a scene similar to Charlotte Street.

If the highway section were decked here as a park or a set of buildings, I’d name it after Lillian Edelstein, the brave Jewish housewife who led the unsuccessful neighborhood effort against Moses’ highway in 1953. The section between Boston Road and Crotona Park was the most controversial as it demonstrated the power of Robert Moses over local lawmakers and civic groups.

The alternative route proposed by Borough President James J. Lyons would have shaved off the northern edge of Crotona Park for the highway route, evicting only 19 families, but also taking out a politically connected bus garage, highlighted on the map above. The Board of Estimate approved the route in a ten to six vote. Moses kept Crotona Park intact and bulldozed dozens of buildings for his preferred route. In total, 1,530 families were displaced in this section. Following the highway’s construction, most local Jews fled the neighborhood. Edelstein outlived Moses at her final home in southern New Jersey, where she died at age 98 in 2015.

Prospect Playground rests atop the highway, offering a preview of how the Cross-Bronx would appear if it were entirely decked across the borough. Prior to the highway, apartments stood here, among the hundreds condemned so that Interstate 95 can run uninterrupted between Maine and Florida. The park’s location is ideal as it is bookended by public schools on two of its sides. Its name is borrowed from Prospect Avenue, which runs next to this park.

View is from the Crotona Avenue bridge facing west.

In 2021, the playground was reconstructed to give it more greenery. Underneath the playground the expressway makes a slight bend, resulting in 176th Street and Clinton Avenue running on top of it. Next to the playground is 1879 Clinton Avenue, built in 1937. Its design shows that there’s plenty of Art Deco in this borough beyond the Grand Concourse.

Admiral Farragut Playground is on the south side of E. 176th Street, partially divided by the highway. Its namesake was a commander during the Civil War. Although he was born in Tennessee, he remained loyal to the Union. He was buried in this borough at Woodlawn Cemetery. His name also appears on a road in Brooklyn and a monument in Madison Square Park.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Between Crotona and Arthur Avenues, the expressway trench blocks a segment of E. 175th Street, but it allowed for enough room to have a pedestrian path that conforms to its route, sandwiched between the towers of the NYCHA Murphy Houses and the highway. The namesake takes us back to the early years of this borough. Arthur H. Murphy was the county Democratic Party chair and an alderman. These towers were built in 1962, a half century after his death. Murphy Triangle at Third Avenue and E. 181st Street is also named for this politico.

City planners love parks that are connected to each other, as they give pedestrians and wildlife a corridor uninterrupted by development and traffic. Prior to the expressway, Tremont Park and Crotona Park touched each other. But rather than a more costly tunnel, master builder Robert Moses had the highway emerge from its trench between these two parks, running for six blocks on a viaduct to Clay Avenue. In 2020 Tremont Park was renamed for Walter Gladwin, the first Black elected official in the Bronx, who served as an Assemblyman from 1953 to 1957.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The viaduct spans a valley where Mill Brook used to flow on its course from Mosholu Parkway to Mott Haven. Brook Avenue follows this phantom stream through Claremont Village, Morrisania, and Mott Haven. Land underneath the viaduct was also designated as parkland and is used for storing city vehicles. This valley also has the Bronx extension of Park Avenue, where the Metro-North Harlem Line runs in a trench.

The 48th Precinct and FDNY Engine 46 Ladder 27 share a building at Washington Avenue and the highway. Every firehouse has a nickname and this one is the Cross Bronx Express, inspired by the highway. This modernist building was completed in 1975, the successor to an older Renaissance Revival precinct building at 1925 Bathgate Avenue that is presently used as a church-run preschool. FNY correspondent Gary Fonville has other examples of former precinct houses across the city.

Where the viaduct crosses Washington Avenue used to be the Tremont Hebrew School, an impressive synagogue that was condemned for the highway. Around 1940, the city’s tax survey took a photo of this synagogue that is no longer with us. On this note, one of my favorite sources on Bronx Jewish history is Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, who was raised on Washington Avenue in the Bronx, and later settled on Washington Street in Jerusalem. Whenever he visited Queens, I had the honor of driving him around.

Looking in the same direction today, we see a police parking lot on parkland under the highway. Impossible to imagine that people prayed here between 1922 and the late 1950s. Where are their grandchildren today? Would the neighborhood still be Jewish today had the expressway not been built? I doubt it, as children of immigrants were seeking the American dream of a suburban home with a lawn. Molly Goldberg’s shouting “yoo-hoo” from her window was losing its charm. When her show had its last season, the fictional Goldbergs were moving to the suburbs. Highway or not, their plot reflected the trends of postwar America.

Cleopatra Playground seems like an exotic name and the credit goes to the pun-loving Parks Commissioner Henry J. Stern. His inspiration was Anthony Avenue, which runs alongside this .62-acre park. The most famous queen to carry this name was Cleopatra VII Philopator, the last ruler of the Ptolemy dynasty in Egypt. She famously killed herself rather than be paraded as a Roman captive. The construction of the highway broke Anthony Avenue into two segments. The blacksmith of the Parks Department had snake silhouettes installed on the park’s gate in memory of the creature that Cleopatra reportedly used in her suicide.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Where the highway transitions from a viaduct to a trench, the steep topography interrupts E. 174th Street on the highway’s south side. Between Clay and Anthony avenues, it runs as a step street. The Bronx leads the boroughs in the number of step streets, with 64 of them according to NY1 News. Kevin wrote his first photo essay on step streets in 1999, when this site was in its infancy. The city’s longest step street is in Riverdale, and the shortest is in Riverside South, with just six steps.

Prior to the expressway, the step street had a more attractive design and benches at its bottom, as seen in these views from the 1940 tax survey photos. The benches and the three-story residence 1725 Anthony Avenue were condemned for the expressway, resulting in an interruption of Anthony Avenue and the steps now overlooking the highway.

On the north side of the highway, a slope walk connects Clay and Anthony avenues, serving as a link between Cleopatra Playground and Peace Park. Prior to the expressway, a set of walk-ups stood on the site of this slope. The apartment building abutting them still stands.

It was hard to imagine how Peace Park got its name as it overlooks the noisy highway trench in a neighborhood that was among the most devastated when the Bronx was burning. When the Cross-Bronx Expressway was completed, Cleopatra and Peace Park were not among the condemned properties. Apartments stood here next to the traffic. It was the urban devastation of the 1970s that resulted in their abandonment, demolition, and transformation into parks. The unique feature in this park is its detailed pergola.

Morris Mesa is one of a dozen places across the Bronx named for the Morris family that had a colonial manor across much of this borough. The last member of the family to have property in the Bronx sold his Morrisania parcels to developers in the 1870s. The park’s namesake is Morris Avenue, which runs through four segments between Kingsbridge Heights and Mott Haven. The park has a tiny playground sandwiched between the expressway trench and apartments that stand on the ridge carrying the Grand Concourse.

Morris Mesa has a small playground and the rest of this park is the steep land along the deep highway trench. Looking west is the underpass below the Grand Concourse, one of the longer underground segments of the expressway. On the south side of Morris Mesa, E. 174th Street also has a tunnel under the Grand Concourse. The subway station here has a unique arrangement that has exits above the tracks on Grand Concourse, and below the tracks on E. 174th Street.

A block north of this park, this segment of Morris Avenue enters an arched tunnel underneath the Concourse and its subway line. Out of the tunnel it becomes E. 175th Street, while another piece of Morris Avenue branches off from the Concourse atop the ridge.

Most of Morris Mesa is too steep to allow for public access, and likewise the case with Walton Slope, the green space on the other side of the Grand Concourse where the expressway trench sees daylight again. This slope is sandwiched between the overpasses of Grand Concourse and Walton Avenue. It is seen here looking east inside the highway trench. Walton Slope, Avenue, and Park are all named for Mary Walton, wife of Lewis Morris, who was one of four New Yorkers whose signature appears on the Declaration of Independence.

The expressway has an interchange with Jerome Avenue, with two playgrounds framed by the ramps that share the avenue’s namesake. Jerome Avenue is named for Leonard Jerome, a financier who owned a horse racing track on the site of Jerome Park Reservoir. This road connected Macombs Dam Bridge to the racecourse. Jeannette (Jennie) Jerome was his daughter, whose name is on the playground framed by the southbound ramps. On a visit to Paris in 1867, the young socialite met Lord Randolph Churchill. One of her sons was Winston Churchill, the WWII British Prime Minister. Next to the northbound ramps is Jerome Playground South, a simple design of handball and basketball courts next to the noisy elevated tracks and highway trench. Parks is planning on adding skateboarding to this park. It is a park in the most unpark-like setting.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The slimmest park formed by the expressway is the .04-acre Townsend Walk, named for the avenue that it touches. It is sandwiched between a car repair shop and a westbound off-ramp, overshadowed by the elevated tracks on Jerome Avenue. But is it a park, as is the equally small Walton Walk, serving as shortcuts on blocks interrupted by the expressway.

Featherbenches is a Henry J. Stern-ism inspired by Featherbed Lane, which snakes down a hill next to the expressway. It is a sitting area overlooking the highway at a dead-end of Inwood Avenue that was broken up by the highway. Kevin walked on Featherbed Lane in 2015, where he shared theories on its name. On the other side of the highway is Inwood Park, an open paved space with London plane trees along its perimeter.

The .36-acre Inwood Park takes its name from Inwood Avenue that was broken up by the highway. Not much wood in this paved sitting area. On its south is Mount Eden Avenue, which widens into a parkway as it goes east towards Claremont Park.

Kwame Ture Recreation Center, wast of Nelson Avenue and north of West 172nd Street, has a baseball diamond behind it that overlooks the highway trench. Originally known as West Bronx Recreation Center, it was renamed in 2021 in a series of 16 new park names honoring African-Americans. The honoree was born in Trinidad as Stokely Carmichae. He immigrated with his family to New York as a child and attended the Bronx High School of Science. At the height of the struggle for civil rights, Carmichael traveled south on a Freedom Ride, joined SNCC, and then promoted the slogan of Black Power. He later shed his English name in honor of his political heroes, anti-colonial leaders Sekou Toure and Kwame Nkrumah. He immigrated to Guinea in 1969. “Real black power requires a land base. The only place where we have a material basis for power is Africa,” he said at the time.

This recreation center is a recent one, completed in 1998 on an empty lot that was devastated by urban decay in the 1980s. In 2008, a dead-end of Shakespeare Avenue was truncated in favor of the sports field. It was one of nearly a dozen parks projects in the West Bronx constructed in exchange for the lost parkland where the new Yankee Stadium stands.

On the same block as this rec center is the highest overpass above the highway. Prior to its construction, this was a middle-class neighborhood with single-family and two-family homes on its highest points, such as 1585 Jesup Avenue seen in this 1940 tax photo. The view west shows a deep trench that could give a high ceiling to the future highway tunnel. The trees on the left hide the sports field of the rec center.

Looking east from the Jesup Avenue overpass, the view down is dizzying as the highway forms a canyon through Highbridge Heights and Mount Eden. I can imagine the roadbed covered here with more apartments and schools. On this stretch it carries two designations: Interstate 95 and U. S. Route 1, which runs in tandem with the interstate between Fort Lee and Webster Avenue.

Plimpton Playground honors local landowner George A. Plimpton who was a publisher, educator, and treasurer of Barnard College. He is also remembered with Plimpton Avenue which borders this park. The playground is in the shadow of Edward L. Grant Highway, an approach road for Washington Bridge.\|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bridge Playground in Highbridge Heights is the westernmost park constructed as a result of Cross-Bronx Expressway, completed in 1957 on land that was condemned to make way for the highway. Prior to the highway, the site of this playground was a green median between Undercliff Place and Boscobel Place, whose name honors Villa Boscobel, the estate of railroad executive and former Chicago mayor William B. Ogden. On my visit the playground was under construction. Looking west, one can see the Alexander Hamilton Bridge carrying the highway to Manhattan.

Ogden died in 1877, the year before Washington Bridge was built. Afterwards, his widow Marianna lost interest in the estate as urbanization encroached. Villa Boscobel was auctioned in 1907 and subsequently developed. Her home in Manhattan stood until 1923. There is another Villa Boscobel in the Hudson Valley that is unrelated to Ogden.

One was unaware that the Ogden Avenues in Chicago and the Bronx were the same Ogden. –ed.

I could not find any images of the Boscobel mansion online, but a G. W. Bromley map from 1879 shows its location in relation to present-day streets. That hilltop site is today’s NYCHA Sedgwick Houses and Sedgwick Playground. An ice pond on that map was a source for Cromwell Creek that flowed south to the site of Yankee Stadium. The outline of the mansion can also be seen on this Belcher-Hyde map from 1901.

This median on Boscobel Place contained a flagpole, benches, and a World War One memorial. This scene from 1935 from the Lehman College collection shows the monument, a billboard for Jacob Ruppert’s beer (he also owned the Yankees), Ogden Theater, and trolley tracks on Ogden Avenue. The highway’s construction eliminated Undercliff Place and this median, took land from Bridge Park, and transformed the Bronx landing of Washington Bridge into a set of ramps rather than an intersection. The neighborhood war memorial was relocated a mile to the south, at Macombs Dam Park. In this century, Bridge Park was expanded along the Harlem River in the shadow of three bridges.

The same view today shows the former Bronx County Trust Company at 1472 Ogden Avenue with the statue of a giant astride the entrance. The statue was installed in 2018 as the mascot of the O’Side Lounge, a food and dance hall specializing in Latino club music.

The color of this plaster giant does not match the exterior of this building. If the O’Side Lounge closes, I doubt that the next business here would retain this statue. My immature side was curious if there was anything hanging under his skirt. Turns out that he is as G-rated as Paul Bunyan, the Jolly Green Giant, and Apache Chief.

Sedgwick Playground is on the north side of the expressway and the ramps connecting to the Washington and Alexander Hamilton bridges. In an undated illustration from the Lehman College collection, the highway was initially planned to run across Washington Bridge, with Sedgwick Park next to its Bronx landing. Most of the proposed park became a NYCHA campus next to a small playground. It is one of the most topographically challenging parks. It takes a hike to reach its play structures.

The precedent for decking the Cross-Bronx Expressway can be seen across the Harlem River, where four apartment towers and a bus terminal stand atop the Trans-Manhattan portion of I-95/U.S. Route 1. The situation isn’t ideal as exhaust and noise rise between the towers to the chagrin of residents. An ideal cover would provide for ventilation and additional decking to conceal the nuisance.

In total, 54 buildings were razed to construct the Cross-Bronx Expressway along with the creation of 44 park spaces. This essay does not name all of them because most of the designated parkland is merely marginal spaces on the shoulders and land under the elevated sections at a time when Robert Moses simultaneously ran the city’s parks and highways. The Department of City Planning site has maps of the highway’s route and the blocks that it broke up.

Similar to the grid-defiant Cross-Bronx Expressway, my essays on Brooklyn’s Meeker Avenue and Rockaway Boulevard in Queens also highlight a series of triangular parks along those routes.

This is my most detailed photo essay to date. As residents, elected officials, activists, and policy makers consider the future of the space above the Cross-Bronx Expressway, I hope that this serves as a useful reference on its history and potential.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

11/14/21