FROM late 2024-early 2025, I decided to walk Manhattan’s lettered avenues from A to D (Brooklyn has the full panoply, with a few exceptions, from A to Z, while Staten Island has an unexplainable and incongruous Avenue B in Port Richmond (see it on this FNY page). While today’s Manhattan’s Avenue B runs only from East Houston north to East 14th, it did continue northward at one time — way up north, at the east edge of Yorkville, where Manhattan Island widens just enough to allow two north-south avenues east of 1st Avenue. One, York Avenue, used to be Avenue A, and an Avenue B was built between East 79th and 90th Streets. In 1890, a year that saw a lot of street naming changes in Manhattan (West End, Columbus, Amsterdam Avenues were all created) Avenue B became East End Avenue. Avenues C and D, though, have always been confined to the East Village.

The north end of Avenue C has altered position over the years. When first laid out on maps, it extended only as far north as East 14th Street. North of that, the island narrowed.

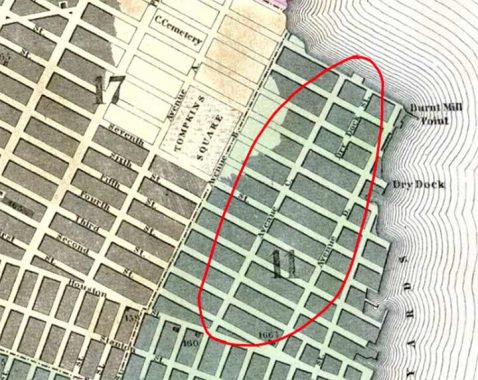

A couple of names on this 1850 map, such as Burnt Mill Point and Dry Dock Street, are no doubt unfamiliar to modern Manhattanites. a story in AM New York by Eric Ferrara in 2012 describes them nicely:

After the Revolutionary War the area remained a popular fishing destination for the city’s elite, like notable poet Fitz-Greene Halleck, a Stuyvesant family friend who fished regularly at Brandt Muhle Point — or Burnt Mill Point — appropriately named after a fire-gutted windmill that once sat on the edge of the salt meadows…”

However, within a few short decades, this peaceful, rural nook was transformed into the center of New York City’s booming marine industry. By the 1840s, massive iron foundries, coal yards and ship docks had risen from the quiet marshland. and the entire neighborhood between Houston and 14th Sts., Avenue A to the East River — today’s “Alphabet City” — became known as the Dry Dock district.

Dry Dock Street is still there; in 1951 the name was changed to Szold Place. The name commemorates Henrietta Szold, the founder of the Jewish Zionist women’s organization Hadassah in 1912.

By 1928 sufficient landfill had been added to allow the lettered avenues to extend further north. Avenue C went as far north as East 18th, with a section that may or may not have been called Avenue C extending along the East River waterfront to East 23rd Street. When the East River Drive was built in sections, in this area from 1938-1940, Avenue C was extended along the drive as its service road beneath the elevated parkway to 23rd Street.

To get to avenue C, the F train on Houston isn’t the best choice, as it turns south after reaching the 2nd Avenue station. Instead, I opted for the L train, which runs east-west on 14th Street and is one of the few Manhattan crosstown lines built; Houston, 42nd, 53rd and 59th also have crosstown lines; the IRT, IND and BMT should have built more. The L heads east to Williamsburg, Bushwick, East New York and Canarsie once in Brooklyn, but I got off at 1st Avenue.

This is the L train’s easternmost stop in Manhattan and the only subway station with the single digit “one” in the name. L train stops, as well as Main Street in Flushing on the #7 train, are the last stations built using mosaic tiles in the signage and decoration, in 1924 and for many stations in Brooklyn, 1928. Designer Squire Vickers went all out, employing a more liberal rainbow of colors than the muted tones of dark green, blue and brown in previous mosaic decoration. Note the differently sized mosaic pieces used in the “To Street” sign, as opposed to the mosaic squares in the “First Avenue” sign. I wonder how it was decided that would be the method.

The MTA later returned to employing mosaics in subway art as part of its “Arts for Transit” project, using mosaics in ways never dreamed of by Mr. Vickers. Katherine Bradford’s “Queens of the Night” was installed in 2021.

Before heading south on Avenue C I decided to walk through Peter Cooper Village first. On 1st Avenue and East 14th Street is this 4-story walkup building that appears to be in the exact same condition it’s been in for decades. As was the practice around the turn of the 20th Century, building owners often had their names inscribed on the buildings, such as C. Wilkens here. You never know, maybe your building will last a century and keyboard warriors will write about it.

The Wilkens name was likely well-viewed by riders on the Second Avenue El, which rumbled past on 1st Avenue until 1942. The el turned west on East 23rd and then north again on 2nd Avenue. More of Manhattan’s “lost” el streets.

What does the Beth Israel/Mt. Sinai Hospital’s glass and metal rotunda, the Linsky Pavilion at East 16th and 1st Avenue, have to do with staplers? Swingline Staplers was founded by Jack Linsky in 1925. Jack Linsky and his wife Belle were collectors of fine art, including works by including paintings by Peter Paul Rubens, Gerard David, and François Boucher. The works were donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and can be found there in the Belle Linsky Galleries. The Linskys were also famed philanthropists, donating millions to charity, and this pavilion was so named because of their generous donation.

The Swingline Building still stands in Sunnyside, Queens, but the manufacturing moved out of the country decades ago, as well as its flashing neon sign.

Duro Carpet’s ancient sidewalk sign, on 1st Avenue near East 20th, uses the Plantin Bold font, which was employed by the Village Voice on its headlines for many years.

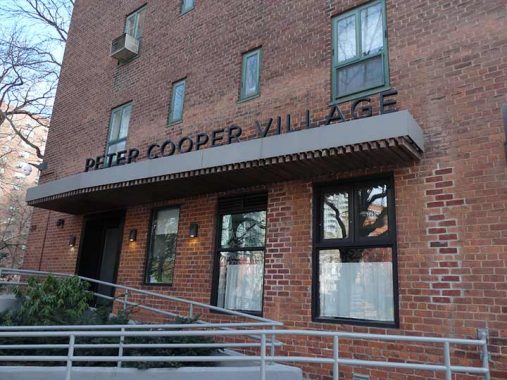

Peter Cooper Village

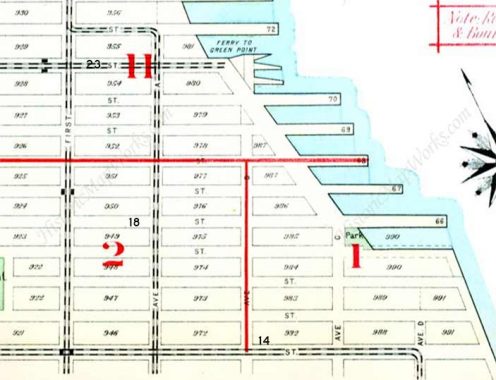

I went north up 1st Avenue because I wanted to use Peter Cooper Road to walk through Peter Cooper Village, located between East 20th and 23rd Streets and 1st Avenue and Avenue C.

Some people mistake Peter Cooper Village for Stuyvesant Town, since the two developments both feature high-rise brick apartment buildings, but the two projects are separate, divided each from the other by East 20th Street, which extends east to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive at the East River perimeter.

Both were built at the same time (late 1940s into the 1950s) by the Metropolitan Life Insurance company to house, at least at first, returning World War II veterans. The massive dual complex occupies 80 acres on what was once 18 square city blocks containing tenements and apartment buildings, as well as Manhattan’s former Gashouse District. In all, 600 buildings were razed and over 10,000 residents were forced to move out to make way for what remains Manhattan’s largest housing complex. It’s a city within a city and contains restaurants, banks, shops and medical facilities, as well as a “central park.” MetLife sold Stuyvesant Town and PCV to Tishman Speyer Properties in 2006, but they defaulted and the complex went into receivership.

In December 2015, the property was sold to Blackstone Group LP and Ivanhoé Cambridge, the real-estate arm of pension-fund giant Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec for about $5.3 billion.

The complex was named for the extravagantly neck-bearded Peter Cooper (1791-1883) , the industrialist-inventor who conceived of the transatlantic cable, the steam railroad engine, and Jell-O. He established Cooper Union, the architecture, art, and engineering school still going strong in Cooper Square, Manhattan. His glue factory for his gelatin and other products was located along Newtown Creek. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery.

Peter Cooper Road is considered a private route and thus not recognized by the Department of Transportation with street signs. These ‘knockoff” versions of the Type G lampposts used in Stuyvesant Town are modular, with the top part of the pole attached to a Type B base. The scrollwork is simplified compared to the usual Type G.

The “forgotten” though busy section of Avenue C, below the elevated Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive.

When I first saw these two-lamp stoplights on Avenue C I was perplexed. Was the Department of Transportation returning to an early stoplight combination, with just a red and green? Both flashed simultaneously as a yellow or “amber” caution lamp.

No. These lights are located on the service roads located within Peter Cooper and Stuyvesant Town that parallel Avenue C and East 20th Street, which have limited connections with their parent streets. A red light, on top, stops traffic, but a flashing red, on the bottom, is “proceed with caution.”

This directional sign meant for pedestrians on Avenue C points toward the Stuyvesant Cove NYC Ferry station at 20th Street. According to the New York State Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), general service signs are blue.

I don’t know much about the Con Edison power plant at the east end of East 14th, east of Avenue C; Con Ed guards their facilities like Fort Knox (rightly enough) and East 14th has been closed east of Avenue C for several years.

The East River Generating Station is a 43,000-square-foot, 660-megawatt oil and natural gas-fired power plant located along the East River at 14th Street in Lower Manhattan.

East River Station was built as a coal facility in 1926 by the New York Edison Company. The plant’s original six-story boilers were so large that one of them accommodated a 100-person luncheon held in honor of the plant’s opening in 1926. Queen Marie of Romania dedicated the plant by flipping the switch that started the 100,000-horsepower turbine generator, prompting a ConEd official to note that the queen had, “released the energies of one machine that could supply more than three times the electricity at present used by all of Romania.” [Belluck Law]

This corner of Avenue C and East 12th has featured various murals for over a decade; last time I was here, singer/activist Gil Scott-Heron was prominent. Pedro Albizu Campos (1891-1965) was a prominent attorney who pushed for Puerto Rican independence, which has not come about yet, though Puerto Rico fields its own teams in international sports competitions. He spent much of his adult life in prison for “sedition.”

This Avenue C apartment complex between East 12th and 13th Street is Compos Plaza, named for the activist. The towers opened in 1983.

Despite its 24/7 schedule advertised on Yelp, Yankee Deli and Pizza was closed on a midday Saturday for renovations. I hope those don’t include removing that great black and white signage in the Clarendon font. Reviews are all over the place.

Between Avenues C and D, East 11th and 12th Streets have been turned into walkways connecting apartment plazas, and their sidewalks and curbs have been removed. You will sometimes find outmoded street lighting in situations like this, and the leftover lampposts have retained their old sodium lamps removed on active streets around 2017.

Classic brick walkup residential architecture at Avenue C and East 10th, animal hospital on the corner with mural.

This low rise building at #151 Avenue C between East 9th and 10th was an auto repair shop in the 1940s. In more recent times it has hosted a number of speakeasy-type watering holes and restaurants, one of which was called Speakeasy. In 2025 it’s Studio 151, featuring sake and a Japanese food menu.

Avenue C features a number of large community gardens, quiet in the dead of winter, tended by local residents. Some have been given official status by NYC Parks, which has appended signage to the fence. At Pancho’s Garden at East 9th, I’m showing its handmade sign.

The Lower East Side of the 1970s was a hard place with little green. Local residents noticed the abandoned, littered lot at the corner of Ninth Street and Avenue C and began to sow seeds and plants along the chain link and among the debris, and so the Ninth Street Community Garden & Park was founded in 1979. Today Pancho’s Garden hosts community events including music, art, and gardening workshops. The garden is half an acre of gorgeous flowerbeds, and vegetable gardens. Meandering pathways crisscross the park, follow them to the koi and turtle pond, fig arbor, or one of many quiet nooks… [Pancho’s Garden]

The largest community garden by far on Avenue C is La Plaza Cultural de Armando Perez, catercorner to Pancho’s Garden on East 9th. Art meticulously crafted from cans and other detritus is affixed to the fence, and signboard displays messages in ASL (American Sign Language); today’s was the initials I, L, Y and the sign for “I Love You.” There are benches, sheds, herb gardens, building murals and sculptures, a library depending on the honor system, and a 1960s-lettered signboard.

La Plaza Cultural de Armando Perez Community Garden was founded in 1976 by local residents and greening activists who took over what was then a series of vacant city lots piled high with rubble and trash. In an effort to improve the neighborhood during a downward trend of arson, drugs, and abandonment common in that era, members of the Latino group CHARAS cleared out truckloads of refuse. Working with Buckminster Fuller, they built a geodesic dome in the open “plaza” and began staging cultural events. Green Guerillas pioneer Liz Christy seeded the turf with “seed bombs” and planted towering weeping willows and linden trees. Artist Gordon Matta-Clark helped construct La Plaza’s amphitheater using railroad ties and materials reclaimed from abandoned buildings. [La Plaza Cultural]

Perez was a local community light who died under suspicious circumstances in 1979.

I was attracted to the simple signage at Wayland across the street on Avenue C, done in Goudy Bold.

I’m perplexed at this mashup of Vikings and waffles, in the building next to the Perez garden. By most accounts, waffles originated in Greece and then spread to central Europe, where they were made in their present form in the Low Countries including what became Belgium; the Belgian waffle is a delicacy that was made famous during World’s Fair II in Flushing Meadows in 1964-1965. Nowhere do I find any connection to Denmark or any other Scandinavian country.

I do like the signage which includes “Viking Waffles” spelled out in Runic characters.

A few doors down, between East 8th and 9th, is another community garden, Flower Door. Tended plants and found neighborhood objects punctuate the stillness. Admittedly, January is not the time of year to visit and many of the gates on the gardens are locked including this one.

This unusual metallic-clad building is “Police Service Area 4” which I understand is different from an actual precinct. I do not know if this is a new building or if the metal coat hides brick underneath. 1940snyc, usually reliable about showing old buildings, is silent about this corner. At Songlines, Jim Naureckas says it “features an exhibit of artifacts found in an excavation of a former privy on the site.” Had I known, I would have entered.

Oof. another thing I missed on my walk. This brick building on the NW corner of Avenue C and East 8th has a chiseled building sign that looks as if it says “St. Mark’s Place.” This street view blowup is fuzzy and indistinct but the lettering has worn down over the years.

I had been under the impression that St. Mark’s Place has always been called East 8th east of Tompkins Square Park, but this may be a simple error by the stonecutter.

1979 seems to be the year when may of “Loisaida’s” community gardens were founded on the sites of empty lots where tenement buildings had been torn down. That’s the year that Carmen Pabón del Amanecer Jardín, a.k.a. Carmen’s Garden, first appeared.

This garden is the site of one of the six original Plant-a-Lot Gardens, a program established by Liz Christy, Director of NYC Council of the Environment at the beginning of the Community Garden movement in the Lower East Side in 1978. [Historical Marker Database]

This garden has a handy map of Alphabet City painted on the wall of the adjacent building.

Dem old kozmic blues again at the Kosmic Community Anti Bar, Avenue C between East 7th and 8th. It has an unusual mission statement:

Kosmic Community Anti Bar is a new place for everybody, though it’s not a bar. Not in that sense, anyway. What set out to be some type of coffee shop and non alcoholic hybrid offering, with a physical bar to sit at, became something more. Really, it became a safe space for your inner child to emerge; that is to say to reconnect with yourself and others and to have FUN without fear of judgement, the way we once did. To go again to that place we all learn to build over, under, and around.Not many of us are comfortable doing that without alcohol, or even know how. That of course is to be expected when you really consider it, and that is okay. That’s what we are here to reclaim. To that point, we are a non-alcoholic space more than we are a sober bar. That’s not to get lost in semantics, but to welcome our differences (and similarities) as people, and to acknowledge that the journey and identity of sobriety is incredibly personal and perhaps unique. We welcome all equally, and have just the non-alcoholic drink for you!

So all that said, the beverage mission slowly informed itself along the way: fun, tasty, and curious drinks that are fitting both in morning and night. We do offer some NA beers, but less so the “mixology” and “mocktail” experience. The menu, while comprehensive, is a really more a starting point and collaboration is encouraged. Combine and suggest to your heart’s content should you feel called to. Maybe it’s an orange nitro coffee cream soda or an iced watermelon ginger, amongst so many other possibilities. Have fun with it, you are warmly encouraged to do so. {Kosmic]

This, along with the 1960s poster-type lettering on the sign, intrigued me enough to perhaps stop in next time I am in the vicinity. Yelp reviews are mostly good, except for some “weird vibes from the owners” comments. The owners or patrons are invited to chime in in Comments.

Ancient bank, NE corner of Avenue C. Even Jim Naureckas in Songlines doesn’t know what bank this was; he describes it as “building that looks like Cthulhu’s bank has housed artists for decades.”

Cthulhu was the gelatinous, octopus-headed dragon of H.P. Lovecraft’s fevered fiction; the Ghostly Gentleman was always peppering his stories with muti-tentacled, multi-eyed Things that were always being summoned by one incantation or other. But he also was quite the philosopher…

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age. (Lovecraft, in The Call of Cthulhu]

Some information about the bank has surfaced: it used to be the Public National Bank:

I found a few NY Times articles on the Public National Bank: In 1920, the bank’s president was Edward S. Rothschild — he made the news when he received a record offer of $1750 a year to lease a building the bank owned at 537 5th Avenue between 44th and 45th. In February 1921 the bank was doing quite well and an embarking on expanding their location at Graham and Siegel in Williamsburg, to a newer bigger lot that they purchased just a block away on Graham. They also had a branch on Pitkin Avenue in Brooklyn, and Delancey at Ludlow in Manhattan. In July of 1921, a teller in their 23rd St. and Broadway branch in Manhattan Ave, succeeded in committing suicide in the bank’s basement by shooting himself in the head. The bank’s 7th and C branch was bought from the J.J. McComb Company in September 1922. A 1990 obit for a former VP and President of the bank, Benjamin Schoenfein, stated that the Public National Bank was acquired by the Bankers Trust Company (now Deutsche Bank) in 1955. I couldn’t find any articles about the E. Village branch closing, but perhaps it happened after Banker’s Trust took over (I’m just speculating). [Forgotten Fan Diane Ingino]

When the Department of Transportation sign shop prepares streets signs honoring past residents, it usually provides the full name. Not here, and I don’t know why the DOT did it like this in this case. The honoree is May O’ Donnell (1906-2004) dancer and choreographer who was with the Martha Graham company for over 60 years, according to Gil Tauber.

“Suspension” was inspired by May’s viewing of a plane flying below her while she was standing atop a hill in California, and is accompanied by T.S. Eliot’s words from Four Quartets. “At the still point of the turning world…there the dance is.” [O’Donnell-Green]

A quartet of interesting sign treatments on Avenue C between East 6th and 7th Streets. I especially liked the serif hand-lettering on ABC Beer (an appropriate name in Alphabet City); however the sign on the awning is redundant. Bob White Counter sells chicken, though it’s named for a different bird.

Prosaically-named Lower East Side II is a grouping of attached brick New York City Housing Authority buildings on East 5th and 6th Streets, very similar to Lower East Side I Infill on Eldridge Street. Both projects were completed in the late 1980s.

I remembered this blue wall from a visit to Avenue C a few years ago, because then it was decorated with some outré versions of letters of the alphabet, in this neighborhood, Alphabet City. I am sorry it couldn’t be preserved as it was. Such is the nature of street art. The time machine that is Street View reveals that it went up in 2016 and was mostly gone. by 2024.

A full name street sign at East 5th honors Adela Fargas, proprietor of Avenue C mainstay Casa Adela:

Casa Adela, open since 1976, became a pillar in the neighborhood under Fargas. It’s known for rotisserie chicken, as well as Puerto Rican classics like mofongo and pernil asado. Celebrities like actress Rosario Dawson have visited the restaurant, but many locals and Puerto Ricans visited for Fargas herself, whose friendly demeanor and welcoming presence made them feel like they were eating grandma’s home cooking at the restaurant. [Eater]

Adela passed away in 2018 at age 81.

I enjoyed the brick and stonework and ogee-arched entrance at #300 East 4th/#51 Avenue C. The building is far removed from any Landmarked realm, so I know little of its history. It is across East 4th from another community garden, the “Secret Garden.” I doubt it, but perhaps it was named for this 1911 children’s classic.

Now for something new: The Stella LES is a new luxury tower fitting on the small plot between East Houston and East 2nd and Avenue C. You can see some interiors here. It was named for theater great Stella Adler (1901-1992).

Though Avenue C begins at East Houston, accepting northbound traffic from Pitt Street, I can’t help but mention…

Remember Microsoft Encarta? I used it as an encyclopedia in the 1990s, as they made a version for Macs; Microsoft only vouchsafed to make a few of their reference programs for Appleheads. I always thought Hamilton Fish was a hilarous name, straight out of kiddie books, but generations of NYC politicians have been named Hamilton Fish…

From the Microsoft Encarta entry on Hamilton Fish:

Fish, Hamilton (1808-93), American lawyer and statesman, son of Nicholas Fish, a New York City alderman, born in New York, and educated at Columbia College (now Columbia University). He was admitted to the bar in 1830. Fish served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1843-45), as the governor of New York State (1849-51), and as a U.S. senator (1851-57). He is most noted for his service as secretary of state (1869-77) under President Ulysses S. Grant, especially for his handling of disputes with Great Britain and Spain. When the Treaty of Washington was drawn up in 1871 to settle the disputes that arose between the United States and Great Britain during the American Civil War, Fish took an active part in arranging for the arbitration of the Alabama claims. Later he was instrumental in finding a solution to the San Juan boundary dispute with England, which was settled in 1872. During the Cuban insurrection against Spain, which dominated Cuban political life in the late 19th century, Fish was largely responsible for the recognition by the U.S. of the insurrectionists.

The Hamilton Fish Play Center is located in Hamilton Fish Park at East Houston and Pitt Streets. It’s a landmarked building designed by Carrere and Hastings, the famed Beaux-Arts architects whose most famed NYC structure is the NY Public Library at 5th Avenue and West 42nd.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission report on the building is refreshingly low on architectural jargon (unlike most of them), and frank about the neighborhood…

The Hamilton Fish Park Play Center is among the most notable small c1v1c build- ings in New York City. Designed in 1898 by Carr~re &Hastings, one of America’s foremost architectural firms at the turn of the century, this park pavilion is an exuberant Beaux-Arts style building that is the only survivor of the architects’ original playground plan. Beautiful in its own right, the building is even more exceptional when considered in relation to its surroundings. Hamilton Fish Park is located in an area that, for over 100 years, has been one of New York City’s most depressed neighborhoods. In fact, the park was constructed as part of a movement to add open space to the densely populated slums of the city. The building was not planned simply as a utilitarian structure, but was designed in the manner of a small garden pavilion placed within a formal park. It was hoped that this sophisticated design would have a positive effect on the area’s immigrant population, lowering the crime rate and improving the respect of the residents for the law and for America in general .

That wraps up A, B and C, and we’ll see if I can get over to D anytime soon.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

2/2/25

6 comments

Hamilton Fish, Hamilton Fish II, Hamilton Fish III & Hamilton Fish IV all served at some level of the federal (Secretary of State) of NY State (US Representative) government. #s II – IV served as representatives represented district upstate on and off from 1908 to 1995. There is a HF V currently alive, though he has not held any elected position.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fish_family

Yes, I always thought it a name suited for the funny papers when I heard it as I was growing up.

Just keeps reminding me of of how much of an eyesore murals really are

I always wondered about the origins of name of the old “Dry Dock Savings Bank”, which was around when I was a kid. Wikipedia says it was from the 1800’s (the elaborate main building was on Broadway and 3rd Street until 1954, https://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2022/03/the-lost-dry-dock-savings-bank-342-343.html. It merged with the Dollar Bank to linger as the Dollar Dry Dock Savings Bank until 1992.

Hamilton Fish II’s nephew was also named Hamilton Fish II (family gatherings must have been confusing). This Fish II had been captain of the Columbia crew team, and volunteered to serve in the Spanish American War. Colonel Roosevelt accepted his offer. He served as a sergeant in the Rough Riders. He died in the first battle of the war in Cuba, at Las Guasimas. His service was lauded by Colonel Roosevelt. That battle was also notable for the prominent combat role of the Buffalo Soldiers, an all-Black regiment.

I used to remember that there was an exit coming down the FDR Drive at 16th Street around that Con Ed Plant, but they closed that one off a while ago.

The block between C & D on 14th Street was open to traffic and pedestrians until the events of 9/11/01. The M14D used to go down that way to turn on and off Avenue D. It was immediately decided that the Con Ed station was a prime target for terrorist attacks so initially 14th was blocked off by dump trucks filled to capacity with sand (plus armored vehicles and the National Guard) then eventually the sight blocking fence there which prevents potential evil doers from visually casing the facility from the street. Nobody has figured out how to prevent drones from flying over the building yet. At some point the gate was open as I was biking down Ave C and I could see further vehicle restrictions such as a heavy duty crossing gate and deployable road spikes just inside the blue fence designed to impede the progress of a large truck barreling thru the fence.

The importance of this power plant for a part of Manhattan was demonstrated later in 2002 when an electrical equipment defect caused an explosion on the side of one of the buildings and a portion of Manhattan was without power for a full day. Years later, Hurricane Sandy caused the East River to overflow and inundate the ground floor of the power plant which again exploded (several times) and plunged parts of Manhattan into darkness. Since then Con Ed has built a flood wall that hopefully will contain any future watery breeches of the landfill that the facility is built upon.