Last week I told of walking east on 29th Street to get to the city’s Park Avenue Summer Streets program, held the first three Saturdays of every August between 7 AM and 1 PM (thus, at this writing, this year’s Summer Streets is over. During the program the city closes Lafayette Street, 4th and Park Avenues from the Brooklyn Bridge north to East 72nd Street, and people are vouchsafed the right to dominate the streets, walking, running, bicycling, whatever they want. There are also musical performances and exhibits along the route. Knowing the event is mostly made for bicyclists and I tend to stumble around looking for things to shoot with my camera, I stuck mainly to the sidewalks along Park Avenue.

In 2010, I did a comprehensive 7-part account of what I found along the complete Summer Streets route.

Art admirer, TD Bank, Park Avenue South and East 32nd Street. Park Avenue has had a convoluted name history — it was originally 4th Avenue all the way north to the Harlem River, then a short section near Grand Central Terminal was renamed Park Avenue, and then the whole shebang north to the river was renamed Park. In 1899 the streets that bordered the NY Central Railroad in the Bronx were also given the name Park Avenue. All this was because of the various extensions of what was originally the New York and Harlem Railroad.

That left the section of 4th Avenue south of Grand Central, and that, too, is complicated. it was renamed Park Avenue only as far south as East 32nd Street, but then another lengthy stretch was renamed Park Avenue South to Union Square. Only the stretch of 4th Avenue from Cooper Square to Union Square kept the name 4th Avenue. And, the same house numbering system encompasses 4th Avenue and Park Avenue South. However, #1 and #2 Park Avenue are found north of East 32nd.

I’ve never been able to find anything definitive about the date 4th Avenue was changed to Park Avenue South and why East 32nd was chosen as the dividing line. I do suspect that it’s because at East 32nd that the street widens in anticipation of the downtown Park Avenue Tunnel, which runs underground between 33rd and 40th Streets. Originally, NY&HRR ran horse-drawn units along 4th Avenue from downtown, but with the advent of smoke-belching steam engines, the tunnel was built in 1852. After railroading south of GCT was banned, the tunnel was used for electric-traction streetcars from 1870-1934, and finally as an auto shortcut in 1937. I’ve only been in a cab that used it once! Here’s an item by the NYC Department of Transportation on the recent improvements made to the tunnel environs.

I hadn’t encountered the famed Silk Clock in the Schwarzenbach Building, 470 Park Avenue South, before; the clock periodically disappears for repairs, but it was apparently in working order when I passed it on PAS and East 32nd. The clock was designed by Marguerite Zorach for the Seth Thomas Clock Co.and installed in 1926. The Schwarzenbachs were silk dealers and fittingly, the clock features sculpted versions of silkworms (actually caterpillars) and the milkweeds that they eat. Like the bell ringers at Herald Square, this is a moving sculpture: “At every hour on the hour, the wizard Merlin raises his wand and taps the squatting blacksmith on the head, who hammers away at King Arthur’s sword, while the Lady of the Lake rises out of the clock’s case.” (Some report the conically chapaeu’d figure as Zoroaster, but thus spake the NY Times on the Merlin ID.) During one of its repair jobs in 1984, Conrad Milster, famed until recently for his steam whistle concerts on New Year’s Eve for his employer Pratt Institute, fixed the clock. I was glad to see it back in place.

East 33rd between Madison and Park was subnamed Sholom Aleichem Place in 1996. The phrase in Hebrew and Yiddish means “peace be to you” but this actually honors Ukrainian Jewish writer Solomon Naumovich Rabinovitch (1859-1916) who used it as his pen name. He is remembered today for his series of stories about Tevye, the pious Jewish milkman, some of which were distilled into the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof. He was published in The Forward, which formerly had offices on East 33rd.

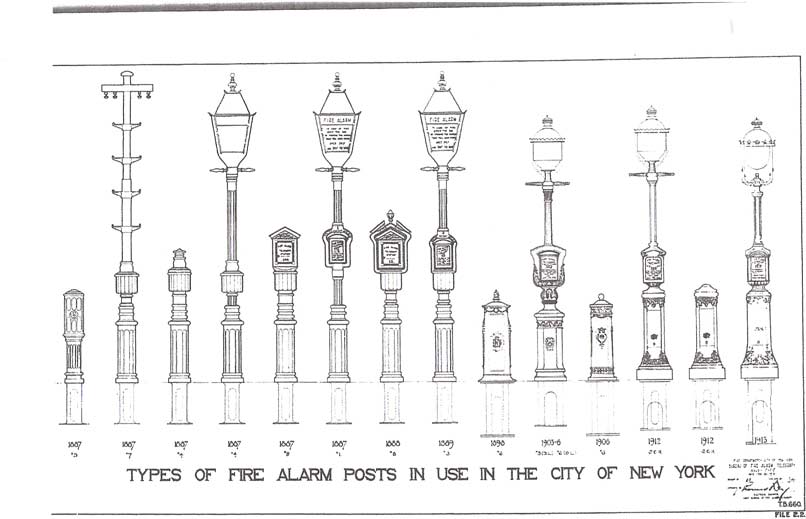

There’s one fire alrm in town I check on every time I’m in the neighborhood. There are hundreds of fire alarms of this vintage — post-1913 — around town; some of which no longer work. This one has had its guts torn out of it. However, this one, on the NW corner of East 34th and Park, is the only one that miraculously has the indicator lightbulb and reflector still in place.

Some of these alarms were marked by indicator lights fastened on nearby lampposts, but some had shafts at the top with bulbs attached. Originally they were made of red glass, but later orange plastic replaced the glass. Years ago, I counted four or five of these around town with lamps attached, and there are dozens with the masts still in place, but this is now the only one with the bulb still there.

I’m also unclear on whether the ramp that takes Park Avenue traffic up over East 42nd Street and around Grand Central Terminal was built. GCT itself goes back to 1913 and it was in fact the second such railroad terminal building on this site. It was faced with demolition like its sister, Penn Station was, but an intercession by preservationists which included the cachet of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis helped save the old barn, which underwent a tip to toe renovation for several years in the 1990s. A plaque on the fence underneath the lamppost on the right dates the ramp to 1919.

The ramp’s original lamps, complete with incandescent bulbs, are still in place; they were renovated along with the rest of the terminal in the 1990s and repainted. Some, though, still have their reddish primary coats of paint.

There was another set of lamps that lit the ramps surrounding the terminal, in this case, sets of twins. About three decades ago they disappeared, only to be replaced with simple pipes with luminaires attached to them. Most of those replacements are still there. However, the city has restored two of the Twins and restored them to the top of the viaduct over 42nd Street where it splits into two roadways.

However, for the centennial celebration of Grand Central Terminal in 2013, GCT turned to Historic Arts & Casting in West Jordan, Utah, which magnificently restored two of the bronze posts to a pristine appearance, and they were subsequently reinstalled. Will other reproductions appear?

Summer Streets allows views east on East 42nd and south on Park Avenue. Such views are nearly almost unavailable from automobiles except if traffic is hopelessly snarled and you’re looking out the windows out of boredom.

A view of the 1921 Bowery Bank Building, now a Cipriani restaurant and grand event space. The interior is 65 feet high, 80 feet wide and 197.5 feet long and is built from marble, limestone, sandstone and bronze. Both the original Bowery bank building downtown at 130 Bowery and here are considered two of the great ec=vent spaces in NYC.

What’s unusual about the twin viaducts is that they not only go around Grand Central Terminal, they also provide access to the Grand Hyatt Hotel at Lexington and East 42nd as the MetLife Building (formerly the Pan Am Building) well as a municipal parking lot, and also tunnel through the Helmsley Building (originally the New York Central Building) through two grand archways.

Looking west from the top of the Park Avenue viaduct toward 330 Madison Avenue. The view was temporarily made available by the razing of 51 East 42nd Street, where I found an ancient toothpaste ad in 2015. Eventually, a building nearly as tall as the Empire State will be built there.

Ironically, this statue of Cornelius Vanderbilt stands athwart the one mode of transportation that he had nothing to do with — auto traffic. Normally viewable only from afar by lowly pedestrians, the statue stands at the head of the Park Avenue Viaduct where the roadway splits in two. It’s actually one of the oldest statues in Manhattan, having been sculpted in 1869 by Ernst Plassman and originally placed downtown at the Hudson River Freight Depot (now largely replaced by the Holland Tunnel entrance). The statue was moved to the south facade of Grand Central Terminal at its 1913 opening.

Part of the viaduct as it enters the Helmsley Building tunnel

One of the lighting stanchions installed in the Helmsley Building trafficway. It’s likely the original reflector bowl was circular with white glass.

A pair of “Wheelie” stoplight stanchions, bereft of their stoplights, stand silently at the Helmsley Building Park Avenue viaduct at East 46th Street. Until about a decade ago, these posts did indeed support three-color stoplights, but the Department of Transportation decided to install new stoplights to replace them. Since the posts have Landmarks Preservation Commission protection, they cannot be torn down and so their only job today is to hold traffic signs, like the backup quarterback holding the clipboard.

“Wheelie” stoplights were first installed at busier intersections in the mid-1920s. Superficially they resembled Corvington lampposts, but with different bases and a car wheel motif in the scrollwork. Since traffic was lighter in the 1920s, as a rule only one Wheelie, supporting a two-color Ruleta stoplight, was deemed necessary.

Wheelies began to be phased out in the early 1950s when the modern-design guy-wired, thick-shafted stoplights were installed. Some hung in there until the 1980s in some cases. This is the only pair remaining except for one ob the 86th Street Transverse Road in Central Park, which has been converted into a streetlamp.

The hardly Forgotten Waldorf-Astoria Hotel takes up the entire block from Park to Lex between East 49th and East 50th. It’s been the preferred lodging of presidents, generals, kings and queens ever since it first opened its doors September 30, 1931, in a then-new building replacing the old Waldorf, razed to make way for the King Of All Buildings at 5th Avenue and West 34th. It had been controlled by the Hilton organization since 1949 until 2014 when it was purchased by a Chinese insurance group. The former hotel is now undergoing renovations that will see most of its rooms converted to rental units and co-op apartments.

An old photograph showing St. Bartholomew’s Church at Park Avenue and East 50th and the office building, since razed, that had been a block north of it. It serves an Episcopalian congregation founded in 1835, with the present Romanesque building (with a Byzantine-style interior) completed in 1919. In 1981 a developer wished to purchase St. Bart’s and demolish it for luxury housing, and court battles about its landmarking dragged on until 1991, when the Supreme Court upheld the landmark designation and the church was saved.

Naturally, I gravitated to this Department of Transportation exhibit concerning the replacement of all streetlamps around town, changing out yellow sodium vapor fixtures to, they claim, energy saving Light Emitting Diode lamps, which shine bright white.

This all strikes me as a massive expenditure especially since the DOT last changed out all NYC streetlamps in 2009, with that process wiping out the remaining green-white mercury vapor lamps around town. Now here comes another regime! Lots of my tax money getting thrown around. The claim is that 60% of the changes have been made, but I note that very little of Staten Island has had any LEDs installed yet.

Concurrently a massive reinstallment of street signs is going on, with capitals changed to initial caps with lowercase. Why they need to do this with numbered signs escapes me, since that refutes their logic that upper and lower is easier to read than all caps.

Sunbleached street signs, which really need replacement, are, of course, seemingly the last signs to be changed.

This is the one that started it all…the very first glass-box building, in NYC at least; Portland, OR’s Equitable Savings and Loan Building claims the overall title. Landmarked Lever House at Park and 53rd was designed by architect Gordon Bunshaft in 1952. Its restaurant has been a 4-star attraction for many years. Many of its neighboring buildings use a complimentary pale green color scheme.

The Lever House hosts artwork in its plaza and windows; past exhibits have included Damian Hurst’s “outrageous” “Virgin Mother.” This time, something rather tamer, Katherine Bernhardt’s “Concrete Jungle Jungle Love” was on display.

That’s all for today, but my walk wasn’t over — I wandered west on 55th Street. More next week.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

8/20/17

11 comments

Wiki can help with Park Avenue Viaduct (Ramp) dating: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Park_Avenue_Viaduct

One of the tenants at the Waldorf Astoria prior to WWII in the south lounge area was an auto parts store. Nil Melior was a hi class accessory store for car mascots/hood ornaments, grille guards, French headlamps , exhaust whistles, driving lights, monograms, wheel discs, etc. I have collected their catalogs and folders offering their products and in fact have one of their cast bronze and brass grille guards fitted to my 1930 Packard. I wrote a history of Nil Melior for Hemmings Classic Car magazine a few years ago.

Yes, Walt: I remember the article well. I also enjoyed your latest column in 10/17 issue of HCC.

“I’m also unclear on whether the ramp that takes Park Avenue traffic up over East 42nd Street and around Grand Central Terminal was built.”

Um, I’m pretty sure it was. Great article though!

I have to say that I love the Lever House for it’s scale, its pleasant and accessible street level courtyard and it’s beautiful turquoise finish.

But it has launched a 60 year series of cynical cold glass boxes that continues unabated (Hudson Yards) today. I must stop as some mediocre talentless architect is about to call me Phyllis Stein.

Happy Birthday Kevin!

Enjoy your special day.

Another milestone flies by…

re: Grand Central:

Three buildings serving essentially the same function have stood on this site. The current building’s large and imposing scale was intended by New York Central to compete, and compare favorably in the public eye, with its archrival, the Pennsylvania Railroad, as well as with smaller lines.

Grand Central Depot[edit]

Looking out the north end of the Murray Hill Tunnel toward the original Grand Central Depot in 1880. The two larger portals on the right allowed some horse-drawn trains to continue further downtown.

Inside the train shed of Grand Central Depot

Grand Central Depot brought the trains of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad, and the New York and New Haven Railroad together in one large station. The station was designed by John B. Snook and financed by Cornelius Vanderbilt. Grand Central Depot first opened in October 1871. The original plan was for the Harlem Railroad to start using it on October 9, 1871 (moving from their 27th Street depot), the New Haven Railroad on October 16, and the Hudson River Railroad on October 23, with the staggering done to minimize confusion. However, the Hudson River Railroad did not move to it until November 1, which puts the other two dates in doubt.[52][53][54][55]

The head house containing passenger service areas and railroad offices was an “L” shape with a short leg running east-west on 42nd Street and a long leg running north-south on Vanderbilt Avenue. The train shed, north and east of the head house, had three innovations in U.S. practice: the platforms were elevated to the height of the cars, the roof was a balloon shed with a clear span over all of the tracks, and only passengers with tickets were allowed on the platforms (a rule enforced by ticket examiners). The Harlem, Hudson, and New Haven trains were initially in different stations that were adjacent to each other, which created chaos in baggage transfer. The combined Grand Central Depot serviced all three railroads.[55]

Grand Central Station[edit]

Postcard of Grand Central Station, circa 1902

Grand Central Station, c. 1902

The exterior of Grand Central Station c. 1904

The interior of Grand Central Station c. 1904

Between 1899 and 1900, the head house was renovated extensively.[22][23] It was expanded from three to six stories with an entirely new façade, on plans by railroad architect Bradford Gilbert. The train shed was kept, but the tracks that previously continued south of 42nd Street were removed and the train yard reconfigured in an effort to reduce congestion and turn-around time for trains.[56] The reconstructed building was renamed Grand Central Station.[22][23]

On January 8, 1902, a fatal train crash occurred in the Park Avenue Tunnel, north of the station. A southbound train had overrun several signals and collided with another southbound train, killing 15 people and injuring many more.[22][23][57] This event prompted William J. Wilgus, the chief engineer of New York Central, to think about alternatives to running a large railway yard in a growing metropolis.[22][23]

On December 22 of that year, Wilgus wrote a letter to New York Central president W. H. Newman, recommending that Grand Central Station, which served steam trains at the time, be completely replaced with a terminal for electric trains. Wilgus stated that electric trains were cleaner, faster, and cheaper to repair.[22][23] In addition, real estate could be built over the 16-block open cut in which Grand Central Station was located. Wilgus proposed a 12-story, 2,300,000-square-foot (210,000 m2) building over the terminal to offset the cost of the station, for a total profit of $2.3 million per year from rents.[22][23] The terminal was to cost $35 million and New York Central made most of its profit from freight. However, the railroad’s board of directors, including Cornelius Vanderbilt II, William K. Vanderbilt, William Rockefeller, and J. P. Morgan, approved the project on June 30, 1903.[22][23]

Replacement[edit]

Between 1903 and 1913, the entire building was torn down in phases and replaced by the current Grand Central Terminal. It was to be the biggest terminal in the world, both in the size of the building and in the number of tracks.[22][23] Before construction even started, objections were raised about the fact that dozens of buildings, on a 17-acre (6.9 ha) plot of land, had to be razed to build the terminal. Wilgus was to head the project.[22][23] Wilgus started to figure out ways to build the new terminal efficiently.[22][23] His solution was to demolish the old Grand Central Station and build the new terminal in sections, while some station operations were shifted to the Grand Central Palace Hotel for a while. This doubled the cost of construction, but obviated the need to suspend all rail service for the duration of construction.[22][23]

not sure about the economics, but i do prefer the light from the new white led street lamps to the yellow sodium vapor fixtures.

In all honesty, I have never been a fan of summer streets. They just block off a major thoroughfare causing for traffic to be relocated to other streets that can barely handle them. BTW, there is a place for great recreation known as parks yet I don’t see them doing anything to make them better. The only good thing about summer streets is that they are only for a few Saturdays in the summer, and I usually don’t drive into the city on that day anyway, so I’m not affect by this. However, I still don’t see the need for this as it just feels like another thing pushed by those anti-car fanatics over at Transportation Alternatives. Just one other thing to ask here. What happens if on one of the days it rains hard? Does it still go as scheduled or are the streets just returned to vehicular traffic as they normally would? The reason I ask this is because I would like to know if this only goes on if weather permitting.

In the early 1980s, I worked for a civil engineering firm which had gotten the contract to design the structural strengthening of the roadway around Grand Central Terminal proper. I worked on the street side of the project, i.e.: lane configuration, the taxi stand at the Grand Hyatt, detours and signage. Back in 1983, southbound traffic wasn’t forced down the viaduct to Park Av South and the tunnel, you could go straight, right in front of Vanderbilt’s statue and continue around north, but it seemed to be used a lot for the hotel, which meant a criss-cross and lots of horns. I also remember trucks coming north around to go to Depew Pl for deliveries. If memory serves me correctly, back then when you came off the viaduct, you could go either way at East 40th St – thru the tunnel or above on Park Av S. Same thing for northbound traffic from the tunnel, viaduct or street. I think there were seperate traffic light cycles for the street and the tunnel, but that wasn’t in the scope of our project.

You got to walk the whole viaduct from 40th St to 46th St without vehicles. We didn’t. Picture working out there to verify survey details with traffic flying by – some of the sidewalks were barely 1 foot wide (45th St southbound viaduct and southbound along Pan Am building), and in may places, it was blocked by the bolt down sign post bases for the No Parking, Stopping or Standing signs. Going thru the Helmsley building, we had to climb on top of the few feet high concrete alongside of the roadway. Safety gear? Hard hat, orange vest, clipboard. Coned off work area – you’re kidding, right? This was “fly by the seat of your pants” because you’re going to “play in traffic” field work!!! Fun and exciting!!!

It was not the church building at St. Bart’s that was planned for demolition and replacement with a luxury tower. It was the community house and open terrace that is south of the church building.