On a Sunday in January 2019, I decided to walk up and down the east-west streets of the northwest region of Greenwich Village, noting that I hadn’t yet taken a close look at them. I began at the 14th Street A/C/E train at 8th Avenue, found Gansevoort, and then zig zagged my way through everything between Gansevoort and West 10th, leaving out West 11th and 12th for the most part because I had already walked down those streets. Instead of one large, interminable post, I have decided to do a Forgotten Slice for each street, so the first one dealt with today will be Gansevoort.

GOOGLE MAP: (NORTH)WEST VILLAGE

Gansevoort Street was named for Revolutionary War Colonel Peter Gansevoort, who in 1777 helped hold off a British onslaught at Fort Stanwix (in upstate Rome) which was one of the first forts that ever flew the Stars and Stripes of the US flag. It’s a very old route and the present street was built atop the colonial-era route called Great Kiln Road, named for kilns (ovens used to make bricks) situated in the area. Gansevoort Street represents the northern edge of the NE-SW-oriented Greenwich Village street pattern and it intersects the prevailing Manhattan grid pattern adopted in 1811. Before the Revolutionary War, though, it was a dirt cowpath beginning at Monument Lane (now Greenwich Avenue) and Fitzroy Road, which runs in the line of the present-day 8th Avenue. When the grid was built up, Great Kiln/Gansevoort was cut back to begin at West 13th Street west of 8th Avenue.

I don’t know whether this is a very old building or not on the SW corner of West 13th and 8th Avenue. If it’s old it’s heavily altered. Just barely, you can make out faded letters above the second floor: “302 Jackson Square Building.” The address corresponds to 302 West 13th.

This is 317 West 13th, opposite West 4th. It’s just north of the overall Greenwich Village Historic District, so building owners could alter the exteriors in any matter they wish; that’s how the building front got modernized.

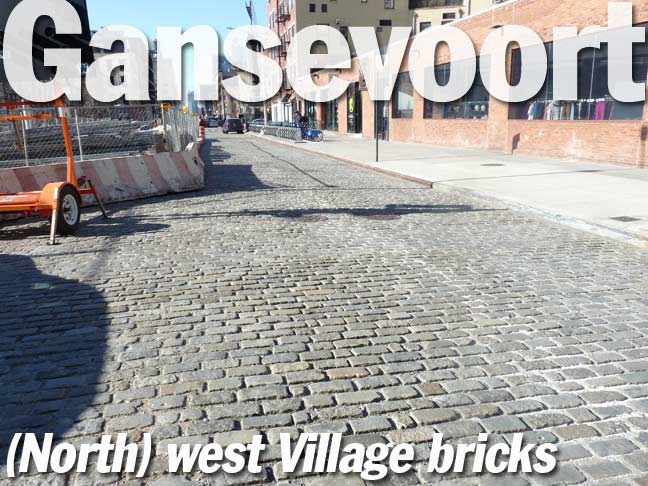

Gansevoort begins at the confluence of West 4th and 13th and runs three blocks west. In some cases, I can’t be sure, but some Belgian-blocked streets, paved with bricks, have NYC Landmarks protection and hence, have not been paved over with asphalt. A number of streets in the West Village, especially in their westernmost sections, still have the bricks, but it’s haphazard, some are asphalted, some bricked.

For NYC newbies, in the Village, West 4th turns northwest at 6th Avenue and intersects 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th. The short story is that long ago, an asylum stood on the street when it was called Asylum Street, and when the asylum was torn down in 1833, the city decided to make it a western extension of West 4th, creating illogical intersections when the other numbered streets also acquired numbers.

Hudson Street, named for the river, is the main north-south street of the West Village. It runs from West Broadway at Chambers northwest to West 14th Street at 9th Avenue. The high rise apartment building falls outside both the Greenwich Village and Gansevoort Market historic districts.

The shadows just weren’t right to get a good look at the angled building at Gansevoort and Little West 12th Streets. There’s a painted sign for the former Middendorf & Rohrs Grocers, built in 1918. Fear not, I got a better shot a few years ago.

I’ve always been fascinated with the confluence of Little West 12th, Gansevoort Streets and 9th Avenue because for decades it was one of NYC’s “great plains” of Belgian-blocked streets. When construction equipment was set up in the area in 2017, I was concerned that the city was getting ready to remove the bricks, but instead, they have recemented the bricks and “tamed” the triangle by setting up curbs, thereby restricting traffic and making most of it a pedestrian plaza.

Toward the rear is 9-19 9th Avenue at Little West 12th. It goes back to 1887 on land originally owned by the Astor family. It was altered in 1921-22 to a simple brick facade with a metal sidewalk awning. In recent years it was the longtime home of the ritzy restaurant Pastis. Despite its Landmarked status, a glass box has been built atop the simple brick facing. The city is bent on heavy development in these parts, and a little Landmarking won’t stop progress.

The trio of small townhouses, #3, 5 and 7 9th Avenue north of Gansevoort, the first addresses on the avenue, go back to 1837.

9th Avenue begins at Gansevoort Street as a northern extension of Greenwich Street, running all the way to West 59th Street, where it changes its name to Columbus Avenue. There is a small piece of 9th Avenue way uptown in Inwood along the Harlem River. Until 1940, an elevated train rumbled above.

This grand old 5-story building at 55 Gansevoort on a triangular plot was designed by architect Joseph Dunn and completed in 1887. Early tenants included the New England Biscuit Works and Elmer Burnham Packing. Faded signs for the biscuit company, as well as Burnham’s “Beet wine” or “beef wine” (I’m not sure which) and “Clam Chowder” and “Clam Boullion” can still be read on the front and sides. Food wholesalers have comprised the majority of the building’s tenants over the years.

A number of restaurants occupied the space at 69 Gansevoort over the years, including the R&L Restaurant, which had been here since at least 1939 and erected this modern facade by 1949. In the 1980s and 1990s, the space was occupied by Florent, one f my favorite spots in the city; restaurateur Florent Morellet took over the space in the 1980s, when the Meatpacking District was occupied by meat wholesalers and employees as well as gay and S&M clubs. Somehow, Morellet was able to create a space where both of those disparate clienteles, as well as photographers wandering around with cameras and families with kids, could feel comfortable. In 2008, Florent shuttered due to the usual reason, a rent increase. A short-lived restaurant followed it and then, the present clothing retailer.

Morellet had provided a succinct history of this previously mysterious, shadowy area on the area’s official website:

The area began as a trading village for the Sapokanican, an Algonquin Indian tribe. After the famous sale of Manhattan Island for a few beads and bobbles, it became a Dutch tobacco plantation, then English farmland, before America built Fort Gansevoort to protect New York during the War of 1812. After the war, New York City began negotiations with John Jacob Astor, who owned most of the Gansevoort area, to purchase the underwater rights for the Hudson River. When the deal was complete, the shoreline, west of what is now Washington Street, was filled in, and became the terminus of the Hudson River Railroad. A farmers’ market emerged, taking advantage of the railroad and the ever-present ferries across the Hudson from New Jersey. In 1886, the city declared the area as a public market to ensure that they participated in the profits!

At the turn of the last century, with the advent of an underground brine-cooling system, the city market was able to sustain a safe meat-market. The buildings that were once dwellings, stores and warehouses were quickly transformed into meat businesses – the vestiges that we still see today. In the past few years, many of the meat businesses have relocated to the Bronx, but a variety of new businesses have replaced them, and adapted these remarkable, historic structures once again – so that the neighborhood retains a vibrant, 24-hour energy that defines Gansevoort as unique in New York City. Meat guys work next to famous retailers, restaurateurs, art galleries and production houses in a wonderful cycle that ensures there is always something for everyone in Gansevoort Market!

rWhat Florent Morellet doesn’t say is that landlords have raised rents to the stratosphere, making it no longer feasible for many of the old meat marketers to remain in their traditional neighbohood, clustered along Washington, Gansevoort, Little West 12th and West 13th Streets. In the 1990s, restaurants, boutiques and galleries, who were more willing to pay NYC’s exorbitant real estate prices, gradually moved in and took over. Gay clubs had begun moving in as early as 1970, with the Zoo followed by the Mineshaft. All, as well as straight hangouts like the biker bar Hogs & Heifers, have bitten the dust.

Chains such as Ample Hills Creamery, an ice cream franchise, and Bubby’s, a deli chain, have moved into the old meat wholesaler spaces.

Though 817-821 Washington Street at Gansevoort was built in 1887, it took its present shape in 1940, when three buildings were reduced in height and connected. After 1940, refrigeration was added and the buildings became home to meat wholesalers. Today, those businesses, 5 in all, are restricted to the west side of Washington Street under the High Line and on the south side of West 13th between West and Washington.

Especially on Forgotten NY, the old West Side Freight Line , colloquially the High Line, needs no introduction; it was constructed as a freight RR complementing the old West Side Elevated Highway (the two resembled each other) and ran from 1934 until the last freight rumbled on it in 1980. It was converted to a linear park between 2005-2009, and opened in sections from 2009-2014. Coverage in FNY:

High Line Before the Hoopla, 1999

Back on the High Line Again, 2009

High Line from 20th-30th Streets

The High Line Section That Won’t Be a Park

… and finally, its last section that opened in 2014.

The High Line has become especially touristy in the last few years, and the surrounding area has been overdeveloped, with high-rise apartment buildings replacing art galleries, mom and pops, and gas stations.

I’ve used this photo a lot — I took it in 2000 outside one of the old meat markets. Compare it to the current scene above.

The Whitney Museum of American Art evolved out of the personal art collection of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a member of two of NYC’s wealthiest and historic families. The Museum was founded in 1931 on West 8th Street, moved to West 54th Street in 1954, to Madison Avenue and East 75th in 1966, and finally to their new glassy, cantilevered headquarters on Gansevoort between West and Washington designed by Renzo Piano, also the architect behind the new New York Times building and new buildings in the Columbia University Manhattanville campus.

According to the Museum’s website, “The Whitney’s collection includes over 21,000 works created by more than 3,000 artists in the United States during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. At its core are Museum founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s personal holdings, totaling some 600 works when the Museum opened in 1931.”

A look at the High Line from in front of the Whitney.

The stolid, no-nonsense 7-story building opposite the Whitney on Gansevoort was built in the 1920s and was home to a number of food wholesalers’ it’s now occupied by small businesses.

The Whitney attracts the tourist trade, already prevalent in the Meatpacking, with a cafeteria and a souvenir shop. In 2019 there was a big Warhol exhibit, and there was plenty of Warhol-themed souvenir items available. Andy, an admirer of pop culture, would have probably approved.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

1/16/19

5 comments

We also have a “hamlet” called Gansevoort, NY, northeast of Saratoga Springs on NY-50. There is a post office there, serving a larger footprint than the hamlet. The zip code is 12831. Wikipedia tells us that it is named for Peter Gansevoort, who was involved not only with the Siege of Fort Stanwix, but also with the Battle of Saratoga. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gansevoort%2C_New_York

Peter Gansevoort was the maternal grandfather of Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick.

Although New York decided to rename Asylum Street after the asylum in question went away, Hartford had no issue with retaining such a peculiar name and to this day Asylum Street remains one of the city’s main thoroughfares. It takes its name from the American Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, today known as the American School for the Deaf.

Fort Stanwix, Rome. Any American geography nut should visit. You can walk from the Hudson River watershed (headwaters of the Mohawk River) to the St. Lawrence watershed (head of Wood Creek) in about a mile on a level urban street (Liberty Street). It blew my mind when I did it. But you wouldn’t understand my joy–unless you’re a geography nut who specializes in watersheds and passes. Go to Fort Stanwix anyway. It’s a National Park.

Flyer for Burnham’s Beef Wine Tonic: https://www.waltergrutchfield.net/images/burnham-flyer.jpg, and history of the Elmer Burnham business, including its predecessor to Jell-O, “Hasty Jelly-Con.” https://www.waltergrutchfield.net/burnham.htm