By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

In his previous crosstown photo surveys, Kevin Walsh walked from river to river on Houston Street, 14th Street, and 155th Street, the highest marked street on the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan. Ten blocks to the south is 145th Street, which has a steep rise and descent, running past historic structures on its way east across Harlem to the Bronx.

At the western end of 145th Street, I documented an abandoned underpass at Riverside Drive. At the time I did not know enough about its history. A subsequent search in the Municipal Archives resulted in a photo from 1908 showing the newly completed underpass, and another from October 1930 showing the underpass being filled.

The rediscovery of these two photos inspired me to travel the length of 145th Street in search of other items worthy of Forgotten-NY. At 186 W. 145th Street, the former P.S. 186 has been beautifully restored to host the Boys & Girls Club of Harlem, along with private residences. Designed in 1903 by prolific public school architect C.BJ. Snyder, it functioned until the 1970s, when it was deemed a fire trap. After the actual school relocated, the old school building stood vacant as one ambitious plan after another failed to gather support.

At Amsterdam Avenue, Mishkin’s Pharmacy still has its neon corner sign, a fossil from a time when such signs were as ubiquitous as today’s LED displays. The corner marks the highest point on 145th Street.

There are so many churches along this street, as in the rest of uptown Manhattan. Truly the bible belt of the borough. Mount Zion Lutheran Church, with its stepped roof design evokes Dutch colonial architecture. This corner of W. 145th Street at Convent Avenue is the heart of Sugar Hill, the upper-class section of Harlem with its hilltop terrace overlooking the rest of Harlem. To its south and west is Hamilton Heights, another scenic neighborhood of apartments, some of them landmarked.

At the southwest corner with St. Nicholas Avenue is a subway entrance that I often used on my commute as a student at CCNY. The station is a typical 1930s IND design of endless bathroom tiles, no artworks. Plenty of police cars parked here and individuals doing the perp walk. On the station’s mezzanine is a transit police precinct.

Above the station is a landmarked apartment building, Sadivian Arms at 695 St. Nicholas Avenue. It even has its own heraldry crest. For years I couldn’t find information on its namesake. It sounds like a place in Italy or Spain, perhaps an imaginary duchy or principality associated with Mediterranean idyll. Perhaps a microstate akin to Andorra, Monaco and San Marino. Not to be confused with micronations, that subculture of pretend polities.

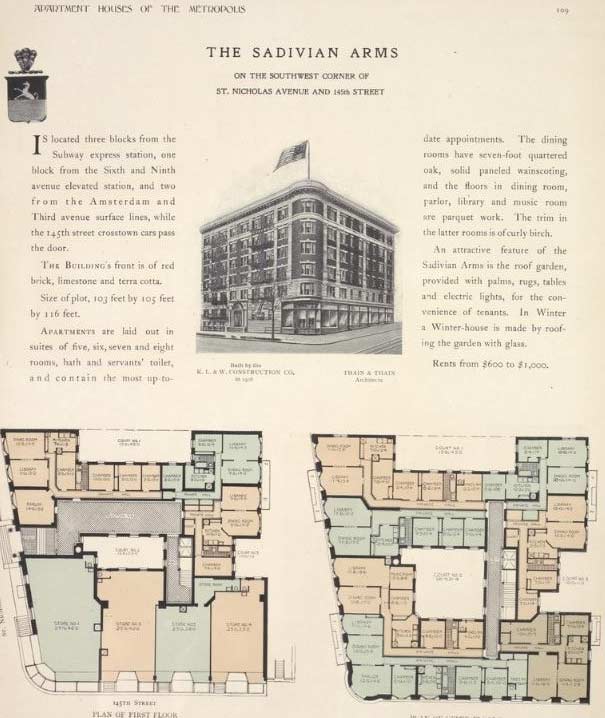

At the time of its construction, it was one of dozens of upscale apartment buildings with names. A detailed description of Sadivian Arms appears in the 1908 guide Apartment Houses of the Metropolis, which features a floor plan, photo and heraldry for the building. A peek into its lobby reveals hints of its former opulence, clad entirely in marble with an unused fireplace.

But I am still curious about its seal. How unique is it? Does it bear any visual relation to a place or noble family in Europe? The property was purchased by developer Robert Leaycraft in 1899, with the building completed in 1906 by the firm Thain & Thain. At that time, its luxury features included a rooftop garden with “palms, rugs, tables and electric lights.” When it comes to Manhattan residential architecture, the top authority is Tom Miller of the blog Daytonian in Manhattan.

But I am still curious about its seal. How unique is it? Does it bear any visual relation to a place or noble family in Europe? The property was purchased by developer Robert Leaycraft in 1899, with the building completed in 1906 by the firm Thain & Thain. At that time, its luxury features included a rooftop garden with “palms, rugs, tables and electric lights.” When it comes to Manhattan residential architecture, the top authority is Tom Miller of the blog Daytonian in Manhattan.

Between Edgecombe and Bradhurst Avenues, the topography north of 145th Street was too steep for development. In 1894 a ten block strip of land between these avenues was designated as Colonial Park. It is the third of such cliff-hugging parks in uptown Manhattan, the others being Morningside Park and St. Nicholas Park.

The layout of these parks is very Olmstedian, giving them the look of a slender and narrower Central Park. The name Edgecombe signifies edge of a cliff, while Bradhurst honors the family that owned the parcel that later became Colonial Park. In 1937, the city commissioned an aerial survey of the park, showing its once-bucolic terrain developed with playgrounds, a pool, and a band shell.

The medieval-revival pool and recreation center contrasts greatly with its Art Deco contemporaries in other parks. In the main lobby, groin vaults lift the ceiling high above the front desk, which resembles the front car of the pilot’s cabin of a boat. The pool opened on August 8, 1936 with a festive ceremony starring Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, the tap-dancing celebrity.

Colonial Park was renamed after Jackie Robinson in 1978 and the lobby received a sculpted bust of the iconic baseball player. In the outer boroughs his name is best associated with the Jackie Robinson Parkway (formerly Interboro) that connects Brooklyn and Queens. In April 2018 this road received its own logo sign with Robinson’s likeness.

On the exterior, the park’s original name (Colonial Park Recreation Center) appears in faded letters. If faded ads interest you, Frank Jump is the leading local authority on this matter.

On the corner of Bradhurst Avenue and 145th Streets are honorific co-names for these streets honoring W.E.B. DuBois and Asa Philip Randolph, respectively. The latter may have resided at Sadivian Arms and DuBois lived nearby. These two were members of an earlier generation of civil rights activists who organized workers, lobbied for anti-lynching legislation, and assisted millions of fellow African-Americans who made the Great Migration to northern states. Randolph attended the 1963 March on Washington, where he had the honor of giving the first speech. In contrast, DuBois had become disillusioned with America and in 1961 immigrated to Ghana, where he promoted Pan-Africanism. He died in 1963 at age 95.

At 256 W. 145th Street is Harlem Grace Tabernacle, the former Odeon Theater according to the fading ad on its side wall. Back in 2001, Kevin published a detailed survey of Manhattan’s former theaters, including this one. The term odeon dates back to the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations.

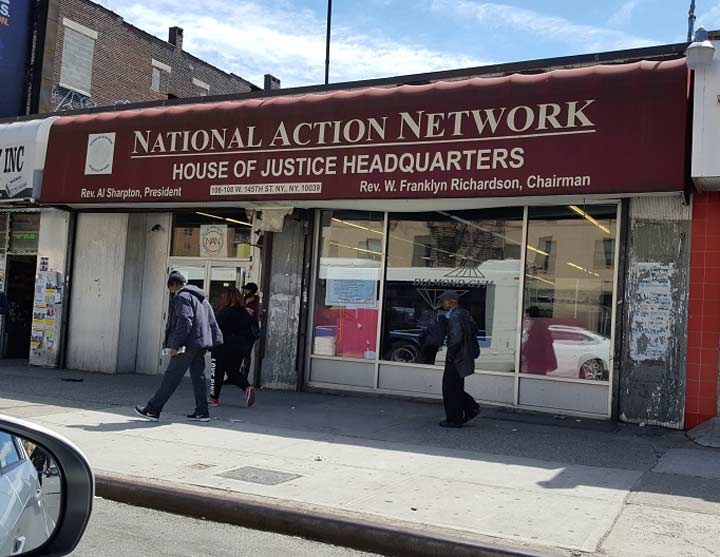

The cultural heart of Harlem is on 125th Street but the activist raises his voice on 145th, where Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network is presently based. The rents are quite high on 125th, and besides this section of Harlem is more working class and minority, the demographic which this organization seeks to empower and assist. Like him or hate him, Al Sharpton is as much a part of this city as a Greek-design coffee cup, bagel, and halal cart. New York wouldn’t be the city it is without him.

At Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard (the former Seventh Avenue) is a likeness of Teddy Roosevelt above a supermarket. In Kevin’s former theater survey, he noted that films were screened here through 1978. The relief memorial was placed here in 1920, the year after the Bull Moose candidate died.

On his 1998 walk across the 145th Street Bridge, Kevin confidently wrote, “With regular upkeep the bridge should last another century or two.” He was talking about the 1905 span, with its antique signs and light fixtures. No one said that Kevin is good at predicting. The old bridge was replaced in 2006 with an updated span that has a wider roadway. Upon crossing the Harlem River this busy road is renumbered as 149th Street, a heavily trafficked route that runs past Hostos College, through The Hub (a commercial district), and past St. Mary’s Park on its way east.

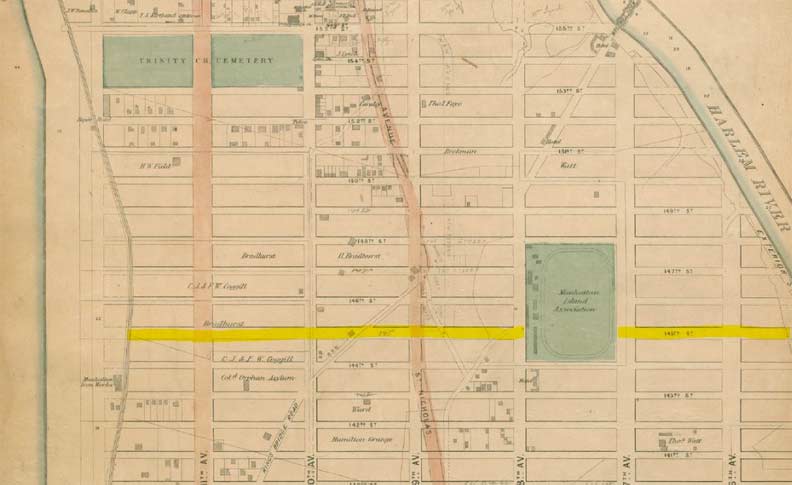

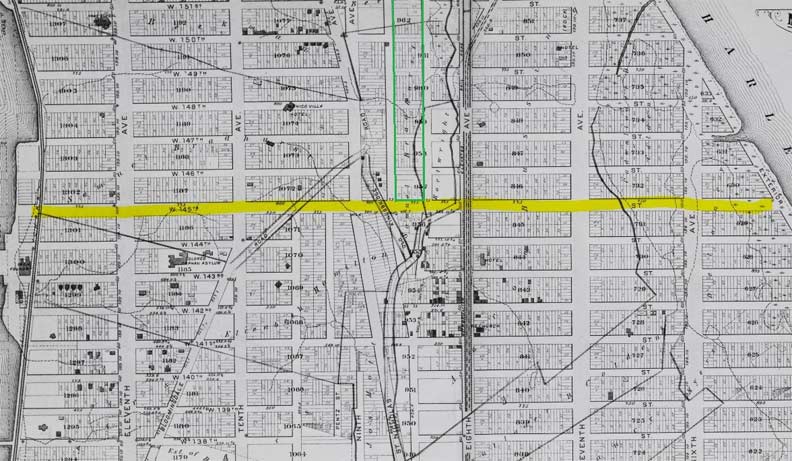

On old maps of Manhattan, there are two which are worthy of sharing. On the 1867 Dripps Atlas, I highlighted 145th Street. The ancient Kingsbridge road of Manhattan is on the lower left, part of it preserve as the grid-defiant Hamilton Place. On the upper right is another grid defiant road, Macombs Place, which leads to the bridge that shares its namesake. Behaving in the same manner as Broadway in Midtown, St. Nicholas Avenue also ignores the grid on its north-south route. The large green space on this map was a private park with a racetrack owned by Manhattan Island Association. Like the Grand Parade ground from the 1811 grid plan, and the old Jones Wood on Upper East Side, this green space did not become a public park.

According to the neighborhood’s Landmarks report, 145th Street was laid out a year before this map was published.

Note the thin pencil lines north of 145th Street between 8th and 9th Avenues. This became Bradhurst Avenue, the eastern edge of Jackie Robinson Park. The unbuilt Ninth Avenue north of 145th Street was renamed Edgecombe Avenue in 1876, after the old Saxon word for cliff.

Looking at the 1879 Bromley Atlas, the entirely of upper Harlem and Hamilton Heights had been parceled out on what had been the estates of Bradhurst, Bussing, and Hamilton. Yes, that Hamilton. I outlined in green the superblock that would become Jackie Robinson Park. The tracks on Eighth Avenue were used by horse-drawn trolleys but by 1879 the street will be plunged into darkness by the Ninth Avenue El. It kept the avenue shrouded until 1940, with its remnant Polo Grounds Shuttle operating through 1958.

From Riverbank State Park to the Harlem River, 145th Street offers a rich display of uptown architecture, black history, and scenic topography.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press)

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

5/6/18

6 comments

Did ya’ll check out of the ad for the Sadivian Arms at St. Nick & 145th Street? It mentioned the Broadway subway (now the 1 line), the 6th & 9th Avenue els and the numerous streetcar lines that were close by. But there’s no mention of the 145th Street station of the Independent Subway that now have entrances virtually in its front door.

Therefore, this indicates the ad was made before 1930, the year the Independent Subway opened.

Since this ad was produced before 1930, did anyone notice the rent prices. It was $600-$1000. To me, it seems like a very high amount for the time. Is there anyone FNY fan who can translate that amount to 2018 dollars?

Using 1930 as a baseline, that $600-$1000 range would translate to $9000-$15000 in 2018. While that is admittedly high even by today’s standards, it looks like renters had from 5-8 rooms, a full bath and a servants bath, which is a pretty large layout. Not a bad deal, if you could afford it in Depression-era NYC.

Those were the rents per YEAR, not per month.

I worked in “the hub” (the Bronx side of the bridge) 1972-74. It was an urban adventure best left to memory.

“Is there anyone FNY fan who can translate that amount to 2018 dollars?”

$600 (1930) = $8,599.67 (2018)

$1,000 (1930) = $14,332.70 (2018)

Results differ from different inflation calculator web sites.

There is a public high school on east 96th st. thats layed out just like the one in on 145.

Its the old cosmetology trades school.

I wish you could get a pic of the old cavalry armory that was turned into a public school on 96th and park.

Explored it when it was vacant as kids.Too cool