Continuing my Manhattan cross streets series. I’ve done them piecemeal in the past, but I’ve already posted 20th Street and 22nd Street in March with more to follow. Today’s entry: 17th Street.

Before the Great Infection, I spent a number of Saturdays (and some Sundays too) crisscrossing Manhattan via its numbered streets. Over the years, I’ve done this quite a few times and I was amazed at how much stuff I missed and how much material I knew about and posted here and there, but never really formalized or categorized. Eventually I might make these “crosstown” posts their own separate category. I’ve already posted much of 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th (twice) and before I get tired of this, I might just do every one of NYC’s numbered crosstown streets, since I had so much fun finding things I never knew about and revisiting things that I did.

After I finish the streets I walked during this time, I’ll add a strip link to all those pages.

A word about the Great Infection. So far I’m more concerned about what it’s done to my investments (which are modest to begin with) but in mid-March, I was admonished to stay indoors after my Facebook photo posts of meandering around Woodside and Sunnyside were seen. Just to be on the safe side, I’ll have to confine myself close to home the next few weeks (months, maybe), whether or not I get ill. I hope everything’s back to normal—healthily and financially—before too much longer!

West 17th Street at its west end at 11th Avenue. On the north side of 17th (on the left) there was a municipal parking lot for many years, but yet another residential high rise taking advantage of Hudson River views is rising in its place. This is the first crosstown street I’ve walked in this series that features an exposed Belgian block roadbed, between 10th and 11th Avenues.

I am continually fascinated with the West Side Freight Elevated which was built in the early 1930s to relieve NYC of street-level freight railroads. Its planners and developers had nothing but good intentions in mind: creating a linear elevated park for all to enjoy. But what they failed to consider—or considered it and ignored it—was that gentrification would follow and drive out longstanding modest businesses, not only gas stations and groceries but also Sebastian Junger’s literary hangout, Half King.

The High Line at #99 10th Avenue at West 17th Street. This is the home of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s NYC office; there are holding cells in the building. The building takes up an entire square block and also is home to a storage company.

This massive structure was once a refrigerated warehouse used to store dairy, meat, seafood and produce for the Merchant Refrigerating Company.

The branch of Artichoke Basile Pizza at 114 10th Avenue at the NE corner of West 17th has a nifty neon sign, but I’m more interested in the pair of painstakingly chiseled street signs on the corner. They are exquisite. Look at that reverse serif on the t in th. Both signs have the Period of Importance that was common on signs up to 1915 or 1920. The New York Times. kept its own on the masthead until the 1960s, and The Wall Street Journal. still has its Period.

The pizzeria used to be Red Rock West, a biker bar with sexy bartenders a la Hogs & Heifers or Coyote Ugly.

Infrastructure is my beat and I’m quite pleased with what the designers of the new High Line (James Corner Field Operations (Project Lead), Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Piet Oudolf) did here as it crosses 10th Avenue at West 17th, a window looking north on 10th Avenue with amphitheater-like seating behind it.

The story of how it was done is here:

The 10th Avenue Square is formed by the High Line’s dramatic crossing over 10th Avenue. When originally constructed, large, oversized steel girders were required to allow the structure to span over 10th Avenue. Given the depth of the steel girders, the architects proposed to cut down into the High Line deck and create an amphitheater. Openings were made in the steel webbing to create cutout windows with a view up Tenth Avenue. [Friends of the High Line]

The Department of Transportation has chipped in with design elements of its own, besides the davit lampposts referenced above. Note that the pedestrian crossing signals, stoplight stanchions and other “street furniture” are painted the same shade of gray-black as the High Line trestle itself.

On 9th Avenue between West 16th and 17th, on one side an exuberant early 20th Century apartment building, on the other, the 1966 Maritime Union Building, complete with portholes, now the Maritime Hotel after a long stint as NYC headquarters for Covenant House, an organization providing food and shelter for runaway and homeless youths. Franciscan priest Bruce Ritter, a professor at Manhattan College, instituted Covenant House in 1972 after several years assisting poor, homeless and runaway youth, and he became the face of the organization on TV ads and mailings. Ritter was forced to step down in 1990 after several allegations of sexual misconduct came to light; nonetheless, the organization continued to thrive and has branched to several cities in the USA. Its current HQ is at 460 West 41st Street.

#248 West 17th, between 8th and 9th Avenues, was once the warehouse for the massive former Siegel-Cooper emporium facing 6th Avenue between West 18th and 19th in the Ladies’ Mile district from 1896-1917. Before the widespread use of motor trucks, horses and wagons would shuttle goods to the store from here. Note the SC digraph on the facade.

#225 West 17th is a new addition on the block and features the plain facades associated with 21st Century designs.

Across the street is #224, which goes back to the late 1800s. This stretch of West 17th is just west of the Ladies’ Mile Landmarked District.

A brace of painted “ghost” ads on the east side of #206 West 17th, near 7th Avenue that include Read Printing and others. Walter Grutchfield is on it.

The Rubin Museum of Art is dedicated to preserving artworks from the Indian Subcontinent, East Asia, as well as Tibet (NYC’s only other Tibetan museum I had known about is in Lighthouse Hill, Staten Island, of all places). It opened in 2004 on West 17th and 7th Avenue in a building formerly housing Barney’s, the longtime Chelsea haberdasher that went out of business in 2019, founded by Barney Pressman in 1923.

These attached brick buildings go back to the mid-1800s and are now associated with the Rubin Museum. The end building on the left, #144 West 17th, was the last home of courtesan/dancer/lecturer Lola Montez, according to NY Songlines‘ Jim Naureckas.

The beautiful Beaux Arts building at #126 West 17th Street is currently Winston Preparatory, a school for students with learning disabilities in grades 4-12. It’s formerly the parochial school associated with St. Francis Xavier Church, on West 16th Street near 7th. Like my old parochial school in Brooklyn, St. Anselm, it has separate entrances for boys and girls, but those restrictions were abandoned by the time I got there in 1960-something.

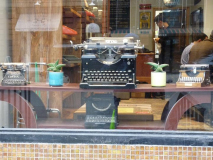

Before settling at 108 West 17th Street a few years ago, Gramercy Typewriter was located at #174 5th Avenue, near the Flatiron Building, for decades. NYC’s last typewriter repair shop has been in business since 1932 when it was founded by Abraham Schweitzer, whose grandson Paul still owns and operates it. Paul is 79, still going strong, but his son Jay works alongside him and so the business may be assured of continuing on for years to come.

Though I have used a computer to write since 1994, I still have a 1940s-era Remington that I used to type school papers and later on, resumes. The ribbon, of course, has long gone dry but I’m pretty sure if I brought it here to Gramercy Typewriter, they could come up with something for me.

What follows is a Forgotten NY touchstone at #109 West 17th I have come back to over and over since its location was pointed out to me by painted sign maven Frank Jump at Frank Jump’s Fading Ads.

It’s a carriage house that possibly has the oldest samples of exterior lettering still extant in NYC. The building was constructed in 1869-1870 by a prominent businessman named Thomas Lord, who as far as I know has no connections to the British department store magnate Samuel Lord, whose Lord & Taylor clothing store spent some time nearby at Broadway and East 20th Street. The building was originally two stories, with the stables on the ground floor and living quarters and a hay loft on the second floor. The third floor was added in 1895 by the building’s third owner — the arched window treatments were almost identically replicated.

The building was always used as a stable and for boarding horses by a succession of owners at least until the early 1900s. Alliance Paper and Twine occupied the building from 1918-1931 and then by Charles F. Wilson, a printer’s supplies dealer, who remained until the 1960s. Until at least the 1980s, lower 6th Avenue had been a paper supplies wholesaling mecca as well as wholesale shoes and socks district, all this coming after the great Ladies’ Mile emporiums had scattered uptown. Beginning in the 1980s, they returned, and Bed, Bath & Beyond, Men’s Warehouse, Old Navy attract thousands on weekends. One notable failure was the Barnes & Noble Books, which largely succumbed to Amazon and Kindle.

OK, the painted sign panels. There are two of them on the second floor, with one saying

TO LET

CARRIAGES

COUPES

HANSOMS

and the other one,

VICTORIAS

LIGHT WAGONS

HORSES

TAKEN IN BOARD

BY THE MONTH.

Both panels feature the address number, 109.

A carriage you’re no doubt familiar with, as those are the rigs that (so their advocates claim) overworked Central Park horses drag around in romantic rides through Central Park. A coupe (spelled with an accented E and pronounced koo-PAY in French) was a four-wheeled, horse-drawn carriage that was based on the larger coach (familiar from the western movies) but smaller and lighter; a hansom was a lightweight horse-drawn carriage invented by British architect George Hansom, light enough to be pulled by one horse.

On the other panel, a victoria was another carriage, but more luxurious and stylish. They were invented in France in the mid-1840s and imported to Britain in the 1860s, where they were nicknamed for Queen Victoria. Wagons were used to transport heavier materials and were pulled along by teams of horses or oxen. Lighter wagons were used to carry lighter materials.

I’d guess these signs are from the 1880s into the 1890s. There’s a certain swashiness (curved lettering) seen in those decades that you don’t see on 1860s and 1870s signage. It’s truly remarkable they’ve survived, as any of the building’s owners might decided to paint them over, but haven’t … yet.

Unfortunately the right panel is obscured somewhat by a banner ad for a cooking school…but it’s still there.

A pair of buildings on the north side of West 17th just west of 6th Avenue—survivors for sure.

Continuing my fascination with narrow buildings, here’s the Queen Anne-style Chelsea Inn at #46 West 17th, constructed as one of the first buildings home to more than one family in 1889; “apartments” were a new thing then. It has been an inn since 1995. Some original detailing is still there.

The Beaux Arts 40-42 West 17th, built in 1910, is home to a French poster gallery, Cerutti Miller.

Barry Supply Co., hardware, #30-36 West 17th, has a really old sidewalk sign, and a front display window with a yellow window shade, with nothing but debris. It looks abandoned but the company website is still active, so the company is still around. The company originated in 1966.

It looks like an innocuous run of the mill display window for a bedding store, but Charles P. Rogers, 34 West 17th, is the oldest surviving bedding company in the USA—since 1855!

Charles Platt Rogers (1829-1917) was an early American industrialist, New York City socialite and charter member and director of the Fourteenth Street Bank of New York. His longest lasting achievement was the founding the eponymous company Charles P Rogers & Co. established in 1855. This is longest continuously operating bedding manufacturing and retail company in the United States. The company continues operations to this day and provided more beds and bedding to the finest hotels and clubs than any other company during its first hundred years. Charles was a pioneer in both the manufacturing processes and importation of brass and iron bedstead and a beloved member of the business community of New York; after his death he was referred to as the “dean of the bedding manufacturers of New York City…” in The Furniture Manufacturer and Artisan Periodical, volume 15, 1918. [Charles P. Rogers Beds Direct]

I dug the terra cotta house numbering at #23-27 West 17th.

Dramatic shadows looking north on 5th Avenue from East 17th. The Gap, in the Pleistocene Era, was home to a beer and pretzels joint called Chew & Sip when I worked in a printer at 200 5th (at 20th Street) in 1981.

I was able to get complete photos of #9 and 11 East 17th Street from the parking lot across the street, which gave me plenty of time to maneuver. While #11 joins most of the buildings on the block from the Beaux Arts era in the early 1900s (and has a terrific cartouche with its address) #9 is a throwback building constructed in 1846, with its storefronts appearing in 1883.

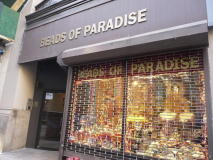

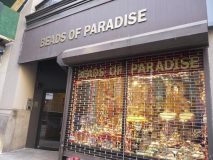

It was near Valentine’s Day and both Brads of Paradise and Journelle #14-16 East 17th were advertising appropriately. You can find anything you want in NYC and that includes stores that specialize in costume beads:

Our inventory now includes goods from Asia, India, Indonesia, the Middle East and Mexico. Our breathtaking bead selection includes glass, metal, wood, shell, gold and silver and semi-precious stones, sold both by the strand and individually. We also carry semi-precious stone jewelry, which is crafted here in the store. Our entire staff is highly trained in bead knowledge, as well as jewelry design and repair. [Beads of Paradise]

Lillie’s, #13 East 17th, is a Victorian-era “theme bar” named for 19th Century British actress/socialite Lillie Langtry (1853-1929). The building dates to 1901, not the bar.

The Hartford Building, #26 East 17th, falls out of the Ladies’ Mile historic district. However, helpful medallions flanking the entrance show its date of completion, 1895. It was built for Hartford Carpet

Looking north on Broadway from East 17th. The corner house was built in 1848, though renovated in 1884, and sports a rather garish paint job. It is known as the Peter Goelet House.

Union Square

Between Broadway and Park Avenue South, East 17th Street skirts the north end of Union Square. Union Square was named (actually as Union Place) in 1815 at the near-junction of the Bloomingdale Road, or Post Road to Albany, and the northern part of the Bowery Road, the Post Road to Boston. In the original Commissioners’ Plan drawn up 1807-1811 by surveyor John Randel, Broadway was originally going to run “north” above Tenth Street and end at a 239-acre military training ground called The Parade spanning between 3rd to 7th Avenues and from 23rd to 34th Streets. By 1814, however, the idea for The Parade had been scrapped as the new Third Avenue diminished the Post Road’s importance.

Union Place, the meeting of the Bloomingdale and Bowery Roads, was so named by 1815, but served time as a potter’s field and a place for squatters until the park’s present configuration west of 4th Avenue (Union Square East), Union Square West (Broadway) East 14th Street and East 17th was finally laid out and landscaped as the modern street grid had reached that far uptown by then. After a short stint as Union Park, the name Union Square was settled on by the 1870s. The square is named for the junction of roads, not the Union (USA, vs the Confederacy) or later gatherings by trade unions that took place there.

In the mid-1800s, Union Square was actually the home of NYC’s entertainment district, that had crept north along the Bowery since the post-colonial era. The story of Union Square’s nightlife era is best told in Luc Sante’s excellent book Low-Life.

So good I shot it twice, the red brick Queen Anne-style Century Building (1881, architect William Schickel) #33 East 17th, was originally home to The Century Magazine and St. Nicholas Magazine for children (which, oddly enough, I remember from seeing reprints of it in the library as a kid). For almost 30 years it has been home to a branch of Barnes and Noble booksellers, and continues in that role as of March 2020; other B&Ns around town have fallen victim to rising rents and Amazon.

Union Square’s north end limestone arch, flanked by two Ionic-columned pavilions, was built in 1929. Though the south end of the park is now where most demonstrations take place these days, the pavilion has historically been the site for marches, sit-ins and protests through the years. There have always been plans for the interior to become a restaurant but so far, only temporary installations have appeared. A new playground opened adjacent to it in 2009.

Through the arch you can glimpse Henry Kirke Brown’s monumental Abraham Lincoln statue. This was the first statue of Lincoln to appear in NYC after his assassination in Washington in 1865, as it was installed in Union Square three years later. A similar Lincoln statue also sculpted by Brown is in the Picnic Grove in Prospect Park in Brooklyn.

Apologies for the bad sun angle. At Union Square’s northeast end, East 17th and Union Square East, is the last version of Tammany Hall, constructed in 1928. Tammany Hall was an organization associated with the Democratic Party that dominated NYC politics for about a century, from the 1830s through the 1930s. The name was a bowdlerization of the name of a (likely fictional) Indian chief. A film school, New York Film Academy, occupied much of the building in recent years. It’s now being refitted as 44 Union Square East as office space. An odd-looking glass dome has already been plopped onto the roof.

W Hotel, 201 Park Avenue South at East 17th, was originally the headquarters of Germania Life Insurance Company, founded by German immigrants, and boasted an early version of neon signage on the roof. The name became a liability when WWI broke out, and it was renamed Guardian Life Insurance (Germania and Guardian have the same amount of letters). The “W Union Square” sign is a very close reproduction in style of the old sign.

I actually got inside as part of Open House New York back in 2005. There are still stylized GLIC’s on the entablatures from the Germania Life Insurance Company days. The ballroom, formerly a bank hall, doubles as a meeting room.

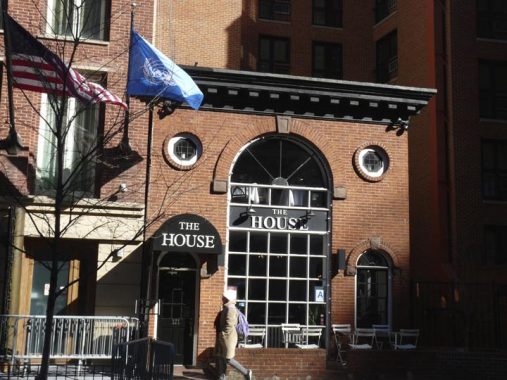

The House is a restaurant at #121 East 17th off Irving Place in what its website describes as a converted carriage house from 1854.

Went here for brunch. You literally feel as if you are stepping into another world when you enter The House. It feels very old New York or perhaps even reminiscent of a Bed & Breakfast in Vermont. The food is not cheap but it is good. The food matches the restaurant – it’s traditional & refined. The House offers a nice combination of upscale cuisine in a relaxed but elegant setting. The bread that morning was so delicious! As it turned out it was from another place I love – Balthazar bakery. The eggs were ok. I preferred the French toast. The waiter forgot my drink but it was such a nice place to just sit and relax that I didn’t mind. I definitely did not feel rushed at all. I left a generous tip. Really enjoyed the experience. Afterwards I took a walk over to Union Square. Great location too. [Yelp review]

If my drink was forgotten about, my tip would be lower, but that’s me I suppose.

118 East 17th is a brownstone called “Irving” which is quite appropriate since we’re a short distance away from Irving Place and Washington Irving High School.

Despite a local legend, there is no evidence that Washington Irving lived here at 122 Irving at East 17th Street — although Edgar Irving (reputed by some as his nephew), lived at #120, next door — and had a son who he named Washington. The building was constructed in 1844.

Beginning in 1892, the building was occupied by actress Elsie DeWolfe, who became a prominent interior decorator, and her partner, literary agent Elisabeth Marbury, who jokingly called themselves “The Bachelors.” The story of the Algonquin Round Table, with its collection of writers, actors and wits, is often told — but no so much The Irving House, where The Bachelors invited George Bernard Shaw, Sarah Bernhardt, and Oscar Wilde in for tea, among other luminaries of the times. It’s possible that DeWolfe began the rumor that Irving had lived here.

One of the handsomest historic plaques in town can be found mounted on the building — it even has its own lamp for nighttime illumination. It features Irving in profile, his birth in New Amsterdam, the future NYC in 1783, his death in Tarrytown in 1859, a scene from his collection Bracebridge Hall and depictions of Rip van Winkle and Ichabod Crane.

Its assertion that “This house was once the home of Washington Irving” is all wet, though. At the bottom are the inscriptions “New York, 1934” and “Fecit A. Finta,” indicating the work of Hungarian sculptor Alexander Finta (1881-1958).

Washington Irving High School, SE corner of East 17th and Irving Place, is currently shrouded in a thicket of construction netting.

The school was constructed from 1911-1913 as Girls’ Technical High School with C.B.J. Snyder, the premier architect of NYC schools, its primary designer. The insides are like a museum, preserving a generous sampling of furnishings and art.

From my Open House 2005 page, which depicts the interior:

[The interior] features beautiful oak panelling in the lobby and a series of murals, one 1915 series in the lobby by Barry Faulkner, a gift to the city by the Municipal Arts Society depicting scenes from early Manhattan; another from the same year on the back wall of the auditorium by illustrator Robert Knight Ryland depicting Dutch and Indians trading; a 1932 series in the front of the auditorium of female figures resembling the Greek Muses by J. Mortimer Lichtenauer; and a 1932 series on the staircases depicting old and new Manhattan by Salvatore Lascari.

Here’s the building on the northeast corner of East 17th and Irving Place. There’s a restaurant, Cafe Mono “Monkey House”, on the ground floor, but take a look at the copper lettering between the windows. It says “52 Irving Place, Entrance On 17th Street.” The building was constructed in 1912 as an apartment house for single men.

And it’s one heck of an entrance, though I wish they would clean the brickwork from the graffiti assaults of the local youth. That looks like the original doorway and glasswork, as well as that terrific wrought iron canopy that keeps the rain off while residents are fumbling for the keys.

This boutique on East 17th used to be called Plastique. A single dress and some flowers remain in the window.

The doorway of #134 is interesting, with a bearded head presiding over a pair of Corinthian columns.

This decorative ironwork on either end of the stoop at #140 East 17th reminds me of the scrollwork used on NYC lampposts of the early 20th Century.

Speaking of worked iron, here’s #141 East 17th. NY Songlines claims that Time Magazine was founded at this address by Britton Hadden and Henry Luce in 1922, with the first issue appearing on March 3, 1923.

Next door at #143 is the diminutive St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church. Could it too be a former stable?

Scheffel Hall is on 3rd Avenue but it’s just off East 17th and I have to mention it.

Scheffel Hall was constructed in a German Renaissance style with a distinctive scrolled gable in 1894. The ground floor was originally a beer hall patronized by the then-substantial German population in the neighborhood. It was named in honor of Joseph Victor von Scheffel (1826-1886), a German-born poet and novelist.

In the 1910s, Scheffel Hall was the home of Allaire’s, a meeting place for local Germans and, some say, a major nexus for German spy activity during World War I. In the early 20th Century it was also a music hall/restaurant frequented by area cognoscenti, including O. Henry, who immortalized it as “Old Munich.” Later, it became the German-American Rathskeller, Fat Tuesday’s Jazz Club and Highlander Brewery.

More photos of Scheffel Hall and lower 3rd Avenue on this FNY page.

East of 3rd Avenue East 17th Street enters the Stuyvesant Square Landmarked District, established in 1975, and it’s a little easier to discover the histories of the buildings. #209 is unique on the block as it has pleasant rounded edges. The Romanesque Revival building was constructed in 1851 and its first owner was merchant William Smith.

On the right side of the picture, the row houses #211-213 East 17th, also built in the 1850s, served as the St. Andrews Convalescent Hospital from 1890-1912.

Directly across East 17th at #210 is the Beaux Arts Monbijou Apartments, constructed 1903-1904. In French, “mon bijou” means “my jewel.”

#225, the French Renaissance East 17th (Hotel 17) was built in 1883 as the St. George residence, named for nearby Episcopal St. George Church on Rutherford Place facing Stuyvesant Square.

Next door is #233 East 17th, originally #231-235 and built as two separate dwellings in 1877 and 1883 respectively, each in a Victorian Gothic style. Both were constructed for the St. John the Baptist Foundation, which sought to administer relief to poor people, mostly German immigrants, who lived in the area’s crowded tenements. The building(s) later housed the Salvation Army.

Just as East 17th forms the northern border of Union Square, it also forms the northern edge of Stuyvesant Square. On this walk I explored the square, but the page is way overdue (because of computer trouble) and thus I’ll skip over it: but I did cover it during my Five Squares walk a few years ago.

Czech composer Anton Dvorak (pronounced, approximately, da-VOR-zhak) came to NYC in 1892 to direct the National Conservatory of Music. His most popular composition may be his ninth symphony, “Music From the New World.” While in NYC, he resided in a building at 327 East 17th Street, just across the street, now occupied by the Robert Mapplethorpe Residential Treatment Facility, named for the avant-garde photographer.

Croatian-American sculptor Ivan Mestrovic’s 1963 bronze of the composer was installed in the east side of the Square in the 1990s.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/1/20

9 comments

I really enjoyed this post, thank you for it. This is a great part of Manhattan and as usual, you described it excellently!

There is a statue of Tamenend (Tammany ) in Philadelphia at Front and Market.

great

For more than a decade, I lived at #211 — the former St. Andrews Convalescent Hospital — in a “studio” apartment that measured 150 square feet. 1980 rent: $247 per month.

The mice-filled cellar had giant spider webs, a dirt floor, and an ominous, bricked-up archway at the rear. Very Freddy Krueger. No one knew what was behind it.

Did you stop short of First avenue for a reason?

I did? maybe I was lazy.

Not like you to skip the very end. I like the beginning and ending pics of your street essays.

Somehow you missed mention of Housing Works on West 17th Street with its large display of furniture.

I lived in Hotel 17 as a child in the the late 1940’s. In fact, 225 East 17 St. is listed on my birth certificate as my “parents” address. I shudder every time I think about the lives they both led. Thankfully, the city of New York got me out of that place and away from them.