PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5

Metropolitan Avenue is one of the lengthiest routes between Brooklyn and Queens. It was first built in 1815, give or take a year, as a toll road and was known along much of its length as the Williamsburg and Jamaica Turnpike until the mid-1800s, when it was bestowed its current name. It runs from the East River to Jamaica Avenue and along the way, marks the southern limit of Newtown Creek, and runs through Lutheran/All-Faiths and St. John’s Cemeteries, as well as Forest Park. It’s the spine of several communities — Williamsburg, Middle Village (so named because it was midway between Williamsburg and Jamaica), and Kew Gardens, and forms the boundary line between Ridgewood and Maspeth.

I have walked along the full lengths of many roads during the 16 years (as of 2015) spent doing Forgotten New York. I usually make two or three trips or so — it took about ten years before I was able to complete Bedford Avenue from Sheepshead Bay north to Greenpoint! It usually doesn’t take that much time;Richmond Terrace on Staten Island took two separate trips in two or three weeks.

I choose the routes I am going to walk full-lengths carefully. The most important thing is, the road has to have a lot of changes — infrastructurally most of all, because that is what I concentrate on, but also the ‘feel’ or atmosphere has to change dramatically along the way. There are a number of lengthy roads in Queens like Francis Lewis Boulevard that are mostly residential; the “Frannie Lou” looks different than its other sections only when it passes through Cunningham Park. I do not want a “sameness” in the pictures.

Unlike my other full-length street pages this time, I did it all in one burst and walked the full length of Metropolitan Avenue in one day, taking about eight hours. I am not a speed walker. My legs are short and I take short strides. Little old ladies can get ahead of me. I am also stopping a lot to take pictures. Had I decided to walk more briskly, I suppose I could have shaved an hour or two off. According to the measurement tool on Google Maps, Metropolitan Avenue is about 8.3 miles from the East River to Jamaica Avenue, so I was going one mile an hour.

My total mileage on the day was 13 miles. That’s because I had to walk through Williamsburg to get to Metropolitan and then down Jamaica Avenue to get to the Jamaica LIRR station, where I got a train to Woodside and then another one to Little Neck.

GOOGLE MAP: METROPOLITAN AVENUE

Throughout its entire length, Metropolitan Avenue defies whatever street grid it runs through in Williamsburg, Ridgewood, Glendale, Forest Hills and beyond. That’s because Met Ave. was laid out first, as the Williamsburg and Jamaica Turnpike in the 1810s (see Part 1 for a complete explanation). However, between Union Avenue and Bushwick Avenue, Met Ave. settles down as just another member of an overall street grid; prior to 1900 or so, it was plain old North 2nd Street, although from the first it was somewhat wider and more important than parallel streets. The BMT Canarsie Line, built from 1924-1928, also runs under Met Ave. between Union and Bushwick.

There has not been a Sparacino’s Bakery on Met Ave. just east of Union Avenue for a couple of decades, but the owner of Desert Island, a comic book store/esoteric bookstore, has retained the vinyl sign since he enjoys the design. (He formerly added a sign called “and comic booklets” in the yellow panel at the bottom of the sign and even sent so far as to duplicate the font as best as possible.)

Crest Hardware has been in business on Metropolitan Avenue for over 50 years and, as I explained on this FNY page from 2012, has had a pet pig on the premises in the past.

A tricolored stoplight shaft at Met Ave. and Lorimer Street indicates the presence of an Italian neighborhood. However, Graham Avenue between Metropolitan and Meeker Avenues, a couple of blocks to the east, is the most manifestly Italian-American boulevard in the region; indeed, Tony’s Pizza, Graham and Conselyea a block north of Met Ave, is my go-to pizzeria around here, and there are other Italian eateries nearby such as the excellent DeStefano’s Steakhouse on Conselyea and Leonard.

The subway entrance is for the (L) Lorimer Street station, which has a transfer to the (G) Metropolitan Avenue station.

When I had walked this stretch of Met Ave. previously a couple of years ago, the taqueria Zona Rosa at Lorimer, named for a neighborhood in Mexico City, operated out of an Airstream trailer. The trailer is still there, but the trailer has gained a corrugated exterior, and the seating has expanded to the sidewalk as well as a rooftop deck.

Bagelsmith, on the SE corner of Lorimer and Met Ave. has added a new neon corner sign. One of the FNY activites I have lined up for the fall and winter, when dusk comes earlier, is to get photos of classic neon signs, as well as the incandescent lamps I know of, to record what they look like when lit.

I’ve noticed something over the years.

NYC is full of bagel snobs, and while I have them once in awhile they are hardly a diet staple. I like them the chewier and softer the better, and have always eaten them with butter, not salmon. I also like the cinnamon raisin.

At 595-597 Met Ave. across from Bagelsmith, there’s an apartment building that practices what I call the “casual elegance” of early 20th Century residential buildings (next to the cleverly-named nails place). It says “M.A.C.C.” above the entrance, which has always mystified me. The M.A. clearly stands for Metropolitan Avenue, but the C.C., well, you got me (it’s not Sabathia.) Any takers?

Normally, I’d grab this handlettered sign at Met Ave. and Leonard from directly in front of it. But I also wanted to get the bottle-shaped illuminated liquor store sign too, and it would be edge on if I moved a few feet to the east.

The fish market sign is in the red, white and forest green of the Italian flag, and the flag itself appears along with the stars and stripes. You see a lot of Italian-owned fishmongers, pasta places, bakeries in the tricolor and there are still so many of them that they could make up their own Forgotten NY post.

A few weeks ago I stumbled on a very entertaining website called Vernacular Typography, which presents what it calls “lettering in the urban environment.” It shows a lot more than storefront signs, but here’s what they have.

Here’s another nearby sign between Leonard and Manhattan Avenue in Italian-flag-color typography. I applaud that in the window signage, the same font as the one used in the storefront sign is employed. It looks fairly recent but the font, known as Hobo, was first cut in 1910!

In a land where aluminum siding is de rigueur, #668 (left) and #666 Metropolitan look nearly as they did when built over a century ago, though #668 has added a different front staircase.

I’ll gloss over Manhattan Avenue because I have already covered it in full on this FNY page, but here’s what I had to say about PS 132 on the NE corner of Met Ave. I did not find any information about the architecture of a public school on the internet, where it’s hard to find.

Located in an area where old-time bagel shops are making way for artsy brunch spots, PS 132 in Williamsburg is changing along with its neighborhood. Principal Beth Lubeck-Ceffalia, who took the helm in 2003 after two years as assistant principal, rearranged and redecorated much of the school, inviting local artists in to paint colorful murals. The building’s overall tone is inviting and pleasant. Whereas test prep and old-fashioned reading-lesson books had long defined instruction at PS 132, classrooms now have such hallmarks of progressive-style education as libraries of children’s literature, and lessons focused on group work. Hallways are wall-papered with student work and art projects. The inviting tone extends to the principal, whose office, on the day of one of our visits, displayed a sign-up sheet for children who wanted to come to read to her. Inside Schools

PS 132 also has the kiddies doing yoga. Your webmaster attempting this in grade school, or even now in 2015, would make for some comical video. Which will never be shot.

#722 Metropolitan Avenue, between Manhattan and Graham Avenues, is a spectacularly rundown-looking former factory, complete with long-bricked-over windows, where art gallery Projekt722 was promoting as I passed in the spring of 2015.

Next door is a partial storefront sign with just enough letters missing to have made it a mystery to me: “EE UNSH.” A World Wide Web search led to something interesting: The City Reliquary (See Part 1) did a special on this former factory which, as it turns out, was Embree Sunshades, an umbrella manufacturer.

This outfit on the corner of Metropolitan Ave. and Graham leaves no doubt what happens within. The same sign is repeated on the Graham Avenue side. This is the L train’s Graham Avenue stop. It turns south on Bushwick Avenue a block to the east.

A number of roads that go to a number of different neighborhoods come together at Humboldt Street and at Memorial Gore, which is a triangle formed by Met Ave., Maspeth Avenue and Bushwick Avenue.

Humboldt Street acquired its present name around 1870. Before that it was called Smith Street. It was renamed for famed scientist and explorer, Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) who is also memorialized by a bust at Central Park West and West 77th Street. He was described by Charles Darwin as “the greatest scientific traveler who ever lived.” Between 1799 and 1804, von Humboldt travelled to South and Central America, exploring and describing it from a scientific point of view for the first time. His description of much of this journey was written up in an enormous set of volumes over a 21-year span. He was one of the first to propose that the lands bordering the Atlantic were once joined (South America and Africa in particular)

Maspeth Avenue begins at Memorial Gore at Metropolitan Avenue and followed a relatively straight line from Williamsburg to Newtown and crossed English Kills via a bridge that is evidenced only by wooden pilings today. Sometime between 1875 and 1890 the bridge ceased to be used, with traffic redirecting to the nearby Grand and Metropolitan Avenue bridges. Today, after it reaches Vandervoort Avenue, Maspeth Avenue ends at Newtown Creek — one of NYC’s longest dead ends. It serves local chop shops and wholesalers. It continues on the other side of the creek where it reaches its titular neighborhood in Queens. In the past decade, new housing has sprung up precipitously, adjacent to the now-closed Greenpoint Hospital.

Bushwick Avenue is named for the 17th Century Kings County town that was a farming community where Dutch settlers grew tobacco for the local market. Later, farmers of Scandinavian, French and English descent moved to the area. Bushwick remained a farming community through the 18th century. Hessian mercenaries settled in Bushwick following the 1776 Battle of Long Island, and began a long tradition of German influence in the neighborhood. “Bushwick” comes from Dutch for “town in the woods.” In the 19th Century, Bushwick became Brooklyn’s chief brewery center, and mansions owned by “beer barons” lined the broad, straight avenue, which runs all the way down past Evergreens Cemetery to Jamaica Avenue.

Memorial Gore contains probably the best-protected war memorial in New York City, surrounded by an iron fence that was probably installed after one too many acts of vandalism. According to the Parks Department the word “gore” refers to a small triangular park, taken from the word’s original meaning of a small odd-shaped or triangular piece of material sewn into clothing to alter the shape. Memorial Gore contains a memorial stature recognizing area soldiers who perished in World War I sculpted by the famed Piccirilli Brothers firm, and dedicated December 5, 1920. Working from their studio in Mott Haven, Bronx, the Piccirillis also sculpted the statue of Abraham Lincoln at Washington’s Lincoln Memorial as well as the twin lions, Patience and Fortitude, at the New York Public Library at 5th Avenue and 42nd Street, and dozens of other instantly recognizable works.

This small house, which is longer than it is wide (here’s an aerial view), is wedged between #1 and #3 Maspeth Avenue. Most NYC streets have odd numbers on one side and evens on the other, so its house number is mystery, but I didn’t feel like pressing the doorbell to get a rude response when inquiring about the house number.

It could be #2 Maspeth, since a number of NYC streets have both odd and even house numbers across the street from a park, and this building faces Memorial Gore.

East of Bushwick Avenue, Metropolitan Avenue once again runs athwart the overall street grid and runs through a curious little neighborhood marked by short streets that do not enter any other part of Brooklyn, such as Orient Avenue, Olive Street, and Catharine Street. The most notable features in the area are Cooper Park and the old Greenpoint Hospital.

Metropolitan and Orient Avenues meet at a sharp angle and form a triangle of greenery called Orient Grove. It has always been used for parkland, the parcel having been sold to the City of Brooklyn in 1896. It was originally called “Cooper Gore” because industrialist Peter Cooper (who founded Cooper Union in Greenwich Village) had a glue factory nearby on Newtown Creek. It was renamed Orient Grove in the late 20th Century, as Cooper has a large park nearby named for him.

Met Ave. east of Olive Street. The street is mixed residential and industrial but little retail in this stretch.

The section of Met Ave. east of Orient Grove settles down into a quiet, two-lane road, albeit one with the occasional clamor of a roaring truck, with small two and three-story residential buildings. A developer got this object started in 2014, but construction had stalled by May 2015. Why only two infinitesimal windows on the west side? The local youth have already made their mark.

Toward Morgan Avenue, Met Ave. becomes nearly completely light manufacturing, warehousing and industrial. This brick building at #1000 has several faded signs on it; the sign seems to read “Isley Bros” wire mesh work, bronze and iron folding gates, but a close look at the metal sign a bit further down actually reveals it as “Estey Bros.”

When I got to Vandervoort Avenue, a block east of Morgan, I had to make a little detour to a couple of oddly named streets, the first of which was Rewe Street which runs east to not-quite a dead end. Rewe Street is dominated by manufacturing firms, the foremost of which is Marjam, which makes wood and metal doors. I also noticed the sign for A to Z Bohemian Glass, which uses a font now out of favor for the most part, Bernhard Modern Bold.

I wanted to see, of course, if Ivy Hill Road, and its 1940s-era porcelain and metal sign, were still there. Correct on both counts. I imagine that the end of Rewe Street, and the entirety of Ivy Hill Road, are private streets owned by Marjam; otherwise, the sign would have been removed long ago.

I have come under fire in some parts for actually revealing the locations of these signs, as Department of Transportation personnel read the site and apparently notify the city about the horrible breach from standard, and crews are dispatched to replace the signs. My feeling is that eventually these signs will be replaced and that my task is to show these signs in situ as a reminder of what NYC signs and other ephemera used to look like.

In any case, I’m mystified why the DOT (and MTA for subway signage) is so manic about removing nonstandard signage — especially when they so legible, like this one. Hundreds of street corners still have 30-year-old, faded signs so bleached by the sun as to be illegible. Yet the DOT allows them to remain, despite a new ongoing sign-replacement program (it seems the faded ones are replaced last!)

Any DOT personnel reading this? Explain yourselves.

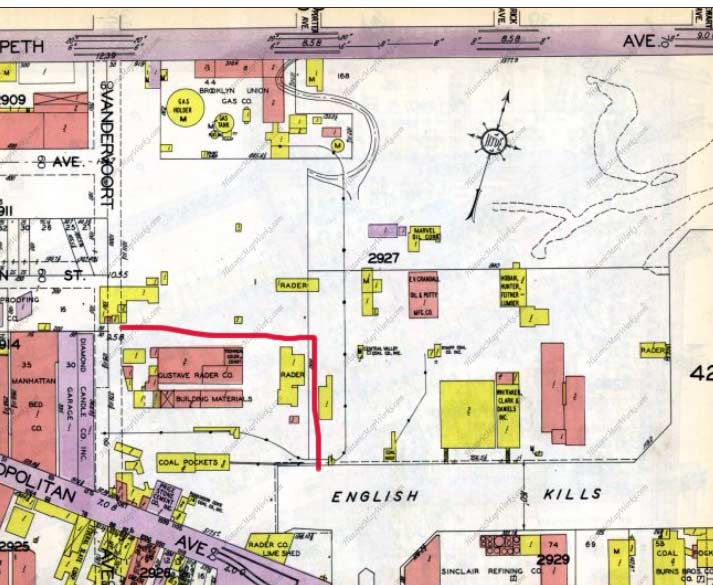

In 1929, Vandervoort Avenue was just a pair of dotted lines on the map and Rewe Street and Ivy Hill Road were nonexistent. They do not even show up on NYC maps until the 1960s, though maps seem to lag a bit behind the reality. The explanation for the names “Rewe” and “Ivy Hill” are a mystery for now, as there are no hills here, ivy covered or otherwise. Here’ I’ve drawn in their approximate routes in red.

As Metropolitan Avenue is about to enter Queens, there’s no doubt here about what you will find on this stretch.

At English Kills, Metropolitan Avenue and Grand Street come together, forming an “X.” They cross the Kills together on the Metropolitan Avenue bridge, a bascule first built in 1931 but with a significant upgrade in recent years:

After the City acquired Metropolitan Avenue from the Williamsburg and Jamaica Turnpike Road Company in 1872, the existing bridge was replaced by a swing bridge, which was also used by the Broadway Ferry and Metropolitan Avenue Railroad Company. Growth in the area made the bridge inadequate by the early 20th century. The current bridge was built in 1931. Modifications since then have included upgrading the mechanical and electrical systems and the replacement of deck, bridge rail, and fenders. The stringers were replaced and new stiffeners added in 1992. Department of Transportation

More importantly, the above photo shows where I tripped on the high curb across Metropolitan Avenue and konked my head on the railing in the spring of 2011. I carried on and even went for lunch at the Clinton Diner (now Goodfellas Diner) with the Master of the Newtown Pentacle, but moving my jaws up and down reopened the wound, and I was dispatched to Elmhurst Hospital and got stitched up; I also requested and received a tetanus shot.

As for English Kills, the first European to catch sight of Newtown Creek was Dutch explorer, trader and cartographer Henry Christiaensen in about 1613. He was searching for advantageous points where the local Native American population, the Mispat Indians, could bring pelts. As time went on the area of Long Island north of what eventually became Calvary Cemetery was settled by the Dutch; south of the cemetery was settled by New Englanders from the former Plymouth Colony. That’s where we get the names of Newtown Creek’s tributaries, Dutch and English Kills, since Dutch Kills empties into Newtown Creek from the north and English Kills, from the south. “Kill” comes from a Dutch word for “strait.”

Between English Kills and Newtown Creek, we’re still in Brooklyn. Varick Avenue, one of a number of parallel north-south routes in Brooklyn’s far east that runs through a nearly all-industrial neighborhood unofficially called East Williamsburg, runs south to Flushing Avenue. Note the double-angled lamps on the telephone poles; there are used mainly in industrial areas so trucks won’t damage them (though they do pop up in residential areas from time to time).

A pair of Ghost Bikes have been installed along Met Ave. in this stretch. They are placed by a worldwide organization that memorializes bicyclists who have been killed by motorists.

As presently configured, the eastern end of Newtown Creek is at Metropolitan and Onderdonk Avenues, as is the border between Brooklyn and Queens. The border runs down the center of the heavily polluted waterway for its entire length. The creek formerly was the boundary between the towns of Bushwick and Newtown; Brooklyn annexed the six towns of Kings County in the 1890s and was itself annexed by New York City in 1898, a year that also saw Queens County dissolve its towns when it joined NYC.

The above-linked Newtown Pentacle explores all things Creek-related, while I have traveled down by boat a few times: this is FNY’s first page on the Creek from 2004.

Looking north along the Creek in these photos you can see the Kosciuszko Bridge, which is on its last legs in 2015-2016, and the sea-green Citigroup Tower.

For one block, and only one block, the Brooklyn-Queens line runs down the middle of Onderdonk Avenue. After its interruption by the freight-only Bushwick Branch of the LIRR, it’s all in the Ridgewood section of Queens and runs past the twin towers of St. Aloysius Church, one of Ridgewood’s tallest buildings.

This block would have made a more interesting exploration prior to the 1980s: that’s when all NYC street signs went green, instead of color-coding by borough. I would have been all over the borderline streets of Brooklyn and Queens to see what color signs were where!

This extraordinarily large building at 46-25 Met Ave. is a NYC Transit Consolidated Revenue Facility. Since it’s heavily gated and guarded, that’s all that the Department of Transportation wants you to know about this building.

Between the creek and Flushing Avenue, Metropolitan Avenue’s south side is lined with a succession of auto salvage businesses.

An ancient campaigner of a warehouse building at Metropolitan and Woodward Avenues contains a modest eatery on the ground floor serving workers of nearby light manufacturing, junkyards and importers.

The Long Island Rail Road crosses both Metropolitan and Woodward Avenues at grade, which is something of an unusual situation in NYC. Most railroads serving passenger lines have eliminated grade crossings in NYC, but freight lines such as the Bushwick Branch, which have several runs a week crossing these avenues, not enough to spend millions bridging avenues over or running them under, rely on grade crossing signals. The ones crossing streets on the Bushwick Branch have new signals installed less than a decade ago (as of 2015). On Met Ave. the tracks pass a Western Beef grocery store and a beer distributor.

On this walk, I discovered yet another building associated with the Bohack grocery store empire of the 20th Century on Met Ave. between Woodward and Flushing Avenues. This building likely contained offices and has the company name spelled out in terra cotta.

Offices, factories and even a luncheonette associated with Bohack still stand at the junction of Metropolitan Avenue, Flushing Avenue and Troutman Street. In this article in Brownstoner Queens, I delve further into Bohack’s origins.

Christmas was still 7 months away when I got here, but you may as well leave the sign up all year. I leave Christmas lights up all they year and plug them in in December only.

Looking east on Flushing Avenue, which has already been walked its entire length for FNY.

In Part 3: Ridgewood into Middle Village

9/14/15

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5

10 comments

Thank you…..Do you do walk tour guide? I think it would be awesome to explore the history of these neighborhood.

The street light arms you show on Varick Ave. originally held 135 or 180 watt low pressure sodium luminaires installed about 1972 or 73. To my knowledge, they were installed in the industrial area of Greenpoint,across the creek in the heavy industrial area of Long Island City,and in the South Bronx in the Spofford area.

I attended a1979 meeting of the IAEI(International Association Of Electrical Inspectors),where Mr. Martin Burrell ,Director of The Bureau of Gas and Electricity,gave a speech on several of the problems NYC faced regarding street lighting. I had the opportunity to ask him why low pressure sodium lamps were being used in only limited areas. He replied that although it was a good source of light,the City could not greatly expand the use of low pressure sodium street lighting because the lamps were imported,which seems pretty ironic now.

Mr. Mulero probably has photos of the arms with the lps luminaires.

Interesting that you’ve covered both blocks I lived on during my 5 years in Brooklyn the past month or so. We lived at 792 Metropolitan, next to the gas station and across from White Castle. In 1998 we brought a baby home to our third floor walk up, and that baby will start college next year.

The Piccirilli Brothers created as well the famed statue of Civic Virtue which stood for decades at Queens Borough Hall and now has been relocated to Green-wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. You can see a photo and read about the Piccirilli Brothers here:

http://georgetheatheist.blogspot.com/2012/07/an-appeal-to-italian-american-community.html

Kevin wrote: In any case, I’m mystified why the DOT (and MTA for subway signage) is so manic about removing nonstandard signage — especially when they so legible, like this one. Hundreds of street corners still have 30-year-old, faded signs so bleached by the sun as to be illegible. Yet the DOT allows them to remain, despite a new ongoing sign-replacement program (it seems the faded ones are replaced last!)

Kevin, it’s a great idea for a future webpage for your site. Have a page detailing all the faded signs that you see and then DOT will replace them.

Hmmmmm

Call me crazy, but you have no idea how happy your words and photographs have made me. I continue to miss living in the City more and more. I look out my window in the Philly suburbs and I fall deeper into depression. I HATE it here. But, I can no longer afford to live in the city of NY which I love. Instead, I get to live my delusional NYC existence through your blog. One of sons lives in Williamsburg so I’m well acquainted with Metropolitan Avenue. I love the run-down splendor. I love the buildings. I love everything. Today was an epic post. Thank you so much!

Between 1947 and 1967 I lived on 60th street around the corner from Metropolitan Avenue. I can still remember the stores that were on the block. I’m looking forward to Part 3.

This is an awesome post… I’m a Californian looking for my Newtown, L.I. ancestors who owned Smith’s Hotel (later renamed Metropolitan Hotel in late 1870s) located at the corner of Metropolitan and Flushing. Would you have possibly taken photos you didn’t post of that intersection? Thank you so much for this invaluable information… I had been having difficulty finding anything showing that intersection from the 1840s-1870s.

The C.C. in M.A.C.C. apparently stood for Construction Corp. At least that’s the name on the 1928 Certificate of Occupancy: Metropolitan Avenue Const. Corp.. The curiosity to me is that it is M.A.C.C. Arms No. 2. Where is M.A.C.C. Arms no. 1?