By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

When it comes to parks that are less than an acre in size, such spaces are usually designated as squares, triangles, malls, gores, and islands. But then there’s the .27-acre Ashmead Park in Jamaica, which is not big enough to host a playground, comfort station, and other amenities associated with parks. Adding to the mystery of its naming is its history, which predates the 1898 annexation of Jamaica by New York City. The park is found by Liberty Avenue, 168th Street, and a turn lane connecting Liberty to 168th.

Fortunately in early 2018, the Parks Department installed a historical sign in this tiny park explaining its origin and namesake. The triangular parcel was purchased by English immigrant couple Alfred and Amelia Ashmead, who decorated it with flowers and then donated it to the village of Jamaica.

In 1914, the Jamaica Women’s Club led by Kate Porter Blanchard teamed up with the Parks Department to operate the borough’s first public playground.

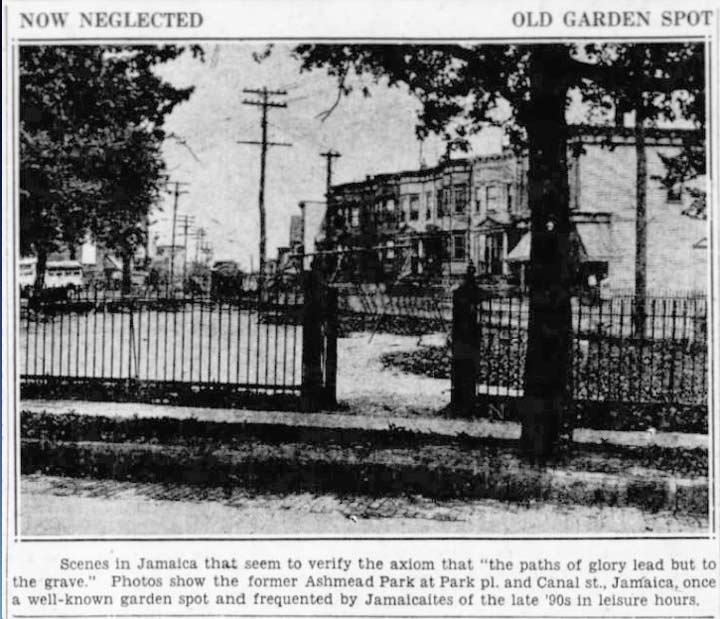

Although its opening day brought out 400 children, the playground fell into disuse a decade later. A 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle photo describes Ashmead as a “garden spot,” but it appears empty. 168th Street at the time was known as Canal Street. There was never a canal here nor any that was proposed. The Canal Streets of Manhattan, Bronx, and Staten Island all have documented waterways from the past. This one remains a mystery.

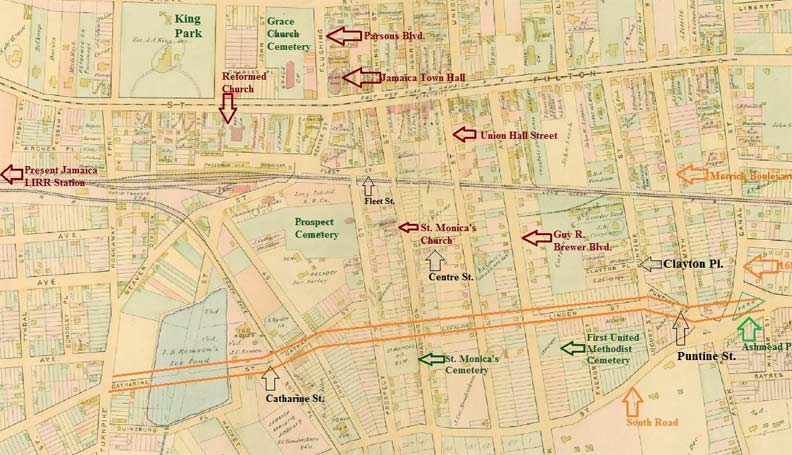

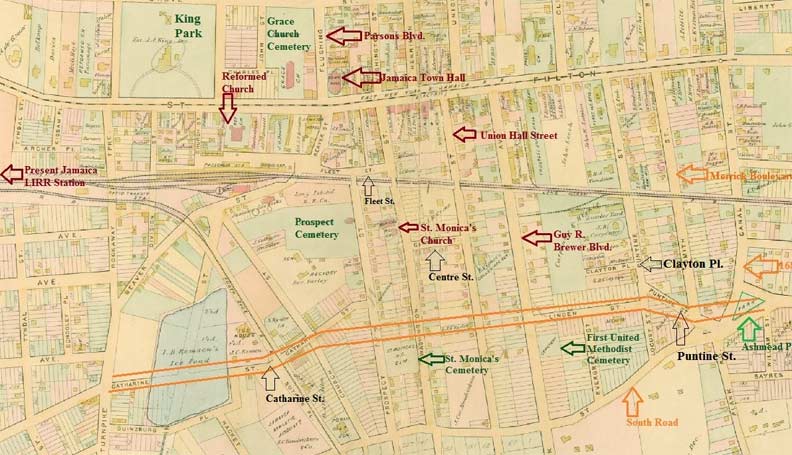

The 1891 Bromley map above shows the eventual path of Liberty Avenue, along with the original size of Ashmead Park. Other long-gone items on this map include Beaver Pond and Jamaica Town Hall. Along the top of the map is Fulton Street, later renamed Jamaica Avenue. In the late 1930s Liberty Avenue was extended through Jamaica, reducing the once-sizable triangular park to its present .27 acres. A tight cluster of shrubs, Parks-issued flagpole, and historical sign are all that’s left to demonstrate its status as a park.

I was thinking of leaving this park as a Forgotten Slice, but then spotted another green space diagonally across Liberty Avenue. The median formed by the merger of Merrick Boulevard and 168th Street at Liberty Avenue was designated in 1939 as Grand Army Plaza, in honor of northern Civil War veterans. But unlike the identically named Grand Army Plazas of Brooklyn and Manhattan, there are no monuments here. Not even a street sign. And this is not a Parks property, the DOT is responsible for this one. Less than a block to the west on Liberty Avenue is a former Studebaker dealership, documented previously by Gary Fonville.

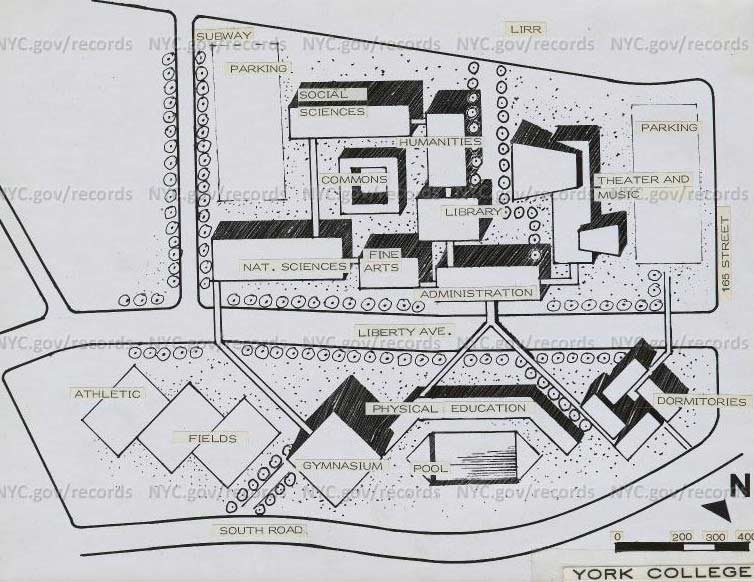

At this point going west, Liberty Avenue runs through the campus of York College, a CUNY institution. Founded in 1966, the college was initially intended to be site at Fort Totten, a scenic but distant corner of Queens. At the time, a 50-acre urban renewal area lay vacant between the Long Island Railroad tracks and South Road, bisected by Liberty Avenue. Local black community leaders and elected officials lobbied the state to bring York College to Jamaica, so that inner-city youth would have better access to higher education. The move was approved in 1971 but the decades’ urban fiscal crisis delayed the completion of the new campus. College President Milton G. Bassin worked tirelessly to reverse Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s cancellation of the campus. Bassin’s name is perpetuated on the college’s performing arts center and with his father’s Yiddish book collection at the campus library.

The initial plan for the campus envisioned two superblocks with pedestrian bridges connecting the buildings in an arrangement akin to CUNY’s Hunter College. At the time of Bassin’s retirement in 1991, six buildings had been completed with the massive Academic Core building. Its size and appearance are reminiscent of the North Academic Center at my alma mater CCNY– described by students as prison-like with minimal decoration. The entrance plaza to Academic Core fronts Guy R. Brewer Boulevard, a rare city street with a full name.

This plaza is a visual feast of modernism with its lengthy stair lines, depressed seating area, and building shadow. The few trees on the plaza are bound within concrete planters.

On the back side of academic core is 160th street, which has subway gratings. In 1989 the long-awaited Archer Avenue subway line was completed with its terminus at Parsons Boulevard. But the E train tunnel continues on for a few more blocks, curving south for a Southeast Queens extension that has yet to be built. The tunnel ends at Tuskegee Airmen Way (South Road) where it was intended to surface and follow the LIRR to Rochdale Village.

A 2011 map of York College shows a pair of dotted lines curving through the campus, marked as “subway easement.” Details on this tunnel stub can be found in Joe Raskin’s book The Routes not Taken. The author grew up in Rochdale Village, which was built with the expectation of having its own subway line. Nearly six decades after its completion, they’re still waiting for the E train to arrive.

In the main lobby, York College has something in common with Kingsborough Community College and LaGuardia Community College– a display of international flags. Each campus has its own vexillological quirks: KCC’s collection includes a few non-sovereign nations. LaGuardia’s is strictly alphabetical and comprised of UN members, while York has a random arrangement that puts Morocco next to Costa Rica, with Taiwan situated between Albania and Argentina. I have no explanation for this arrangement. Non-sovereign flags hanging here include Macau and Netherlands Antilles.

Inside and around the Academic Core Building there are 23 art installations, many of them evoking black history. On the 160th Street side of the building is Houston Conwill’s Arc, completed in 1986. Inspired by the art of the Kongo people, it features designs native to West Africa, the ancestral home for most African-Americans. To me, the squares appear as miniature villages emptied of their residents.

The main lobby of the Academic Core lines up with Union Hall Street, preserving the street grid with its lengthy atrium. The big artwork here is the hanging piece, Martin Puryear’s Ark which recalls the slave ships that brought his ancestors to America. Puryer’s interest in Africa include a two-year Peace Corps service in Sierra Leone, where he picked up native woodcarving techniques while teaching art and English.

The main lobby’s art collection also includes a replica of a fighter plane piloted by the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, who have a nearby street named after them. Titled Copper Airplane, this James L. Johnson piece was installed in 2003.

At the northern end of the main lobby one can see Union Hall Street beyond the train tracks. The street’s namesake was Union Hall Academy, a school that operated from 1792 through 1873. Considering that there was already a York College in Pennsylvania, Bassin and the CUNY leaders could have revived the name Union Hall for this college or at least for its main building, lending it a feel of historical continuity. Most of CUNY’s campuses are named after places rather than people, the exceptions being Baruch, Guttmann, Hunter, LaGuardia, and Lehman. The sculpture on this demapped portion of Union Hall Street is titled Build-Grow by Richard Hunt.

Any talk about Union Hall Street would be incomplete without mentioning the north side of the train tunnel, where the abandoned westbound platform has fake windows reminiscent of those that appeared throughout the South Bronx in the 1980s. This station never had too many users on account of its proximity to the Jamaica station and the nearby subway line. It closed in 1977. Certainly it would be nice if York College had its own train station with a platform within a minute’s walk to the classroom.

The campus of York College also has the distinction of having three cemeteries within its borders. Prospect Cemetery is very well documented, thanks to historian Cate Ludlam, and ForgottenTours 15, 51, and 103. Less visible are Saint Monica’s Cemetery and the Methodist Cemetery, both built by nearby churches. Eventually these pocket graveyards filled up, descendants moved on, and so did their churches.

While Saint Monica’s Cemetery is well maintained, the Methodist plots are overgrown with vegetation, and cleared sporadically by volunteers. These days, many New Yorkers opt to avoid the cost of burial and the trouble of perpetual care and visitation by having their remains cremated. Although Methodism allows for it, and Catholicism permitted cremation in 1963, other faiths such as Islam and Judaism expressly forbid it.

Behind the Methodist Cemetery is a huge lawn used for overflow parking, intended for buildings but still empty as of 2018. I am not sure how long this lawn will remain empty, but it’s rare to see so much open space that is not a park or parking lot.

The former St. Monica’s Roman Catholic Church dates to 1856 but was abandoned in the 1970s. All that remains of it is its steeple, preserved as part of the college’s child daycare center. The first Catholic church on Long Island, it counted the young Mario Cuomo among its congregants. Its final mass took place in 1973, followed by nearly three decades of abandonment and neglect. This former church isn’t the only one in the city repurposed by a university. In the East Village, NYU demolished St. Ann’s Church on E. 12th Street in favor of a boxy dorm tower, but preserved its historic steeple. Higher learning from a Higher Power.

The restored chapel at Prospect Cemetery has a new function as the Illinois Jacquet Performance Space, named in honor of a renowned local resident who composed and performed jazz on his tenor saxophone. The repurposing of an unused structure next to a college campus into a performing arts hall is reminiscent of The Gatehouse at my alma mater– a historic abandoned pumping station turned theater.

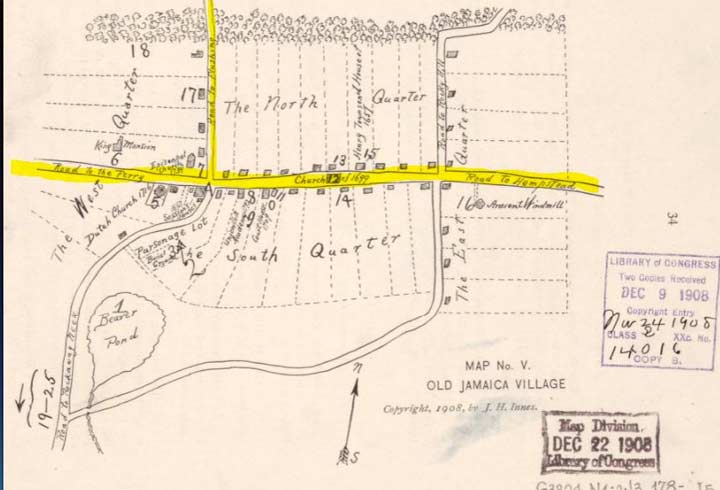

No visit to an urban renewal area would be complete with a necrology of streets that were wiped off the map. The 1908 J. H. Inness replica of how colonial Jamaica appeared shows it as a village with five connecting roads: to the Rockaways, Brooklyn, Flushing, and Rocky Hill. The South Quarter of the village is where York College would be located.

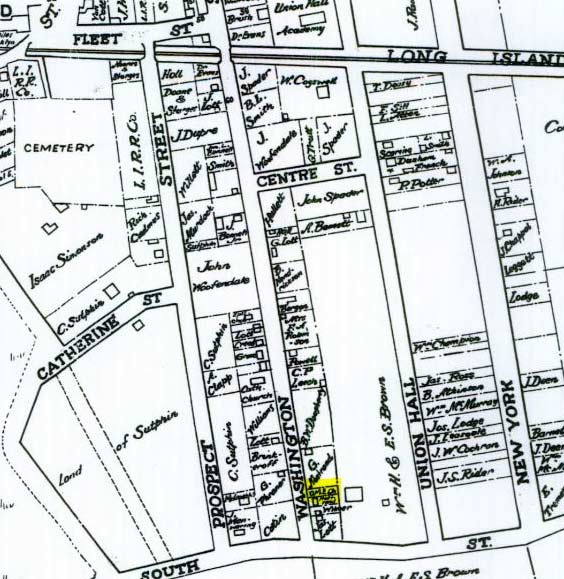

On the 1842 map of the future campus, I highlighted the local A.M.E. church on 160th Street. Black history in the South Quarter of Jamaica goes back to colonial times. This church was founded in 1834, named after Rev. Richard Allen who founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1816 in Philadelphia for slaves and free blacks. As this church grew, it became a cathedral, relocating in 1968 to its present location on Merrick Boulevard and Sayres Avenue. The 1842 map also features Prospect Cemetery on the upper left and Union Hall Academy at the top center. The Great Migration between the world wars and Afro-Caribbean immigrants in the postwar decades added numbers to the established black community in Jamaica.

On the 1891 Chester Wolverton atlas, I labeled the demapped street with black letters, present-day roads in orange, Ashmead Park, the three cemeteries of York College, and the eventual route of Liberty Avenue slicing through this old grid. Beaver Pond is labeled here as Remsen’s Ice Pond. It would be drained in 1906. Streets that were later removed include: Puntine, Clayton, Centre, Catharine, Fleet, Evergreen, and Locust. The rest were given numbers conforming to the borough-wide grid.

The urban renewal area that became York College was comprised mostly of low-rise wooden structures that did not have distinctive architectural features but contributed to the history of Jamaica. The Antioch Baptist Church was carved into the earth on 160th Street. It was documented by Percy Loomis Sperr in 1932.

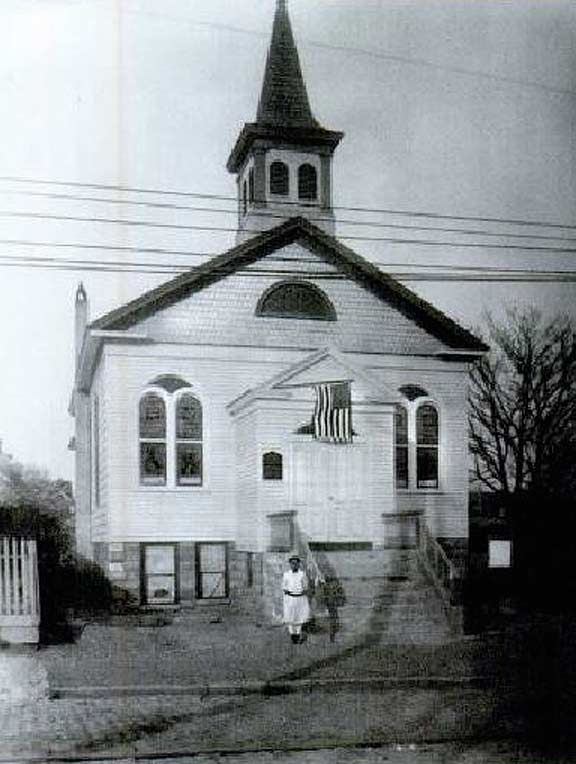

On the same street, Allen AME had its church. From the Queens Library collection is a photo of its second church, which stood from 1869 until 1933. Jamaica Hospital had its building on Guy R. Brewer Boulevard from 1891 to 1924, when it moved to its present location on Van Wyck.

On the 1918 map of the area, I circled Jamaica Hospital in blue. Ashmead Park appears here as a triangular widening at South Road and 168th Street, clearly not important enough to appear as a park.

York College has gone a long way since its founding in 1966. As every college has its logo and official colors, this one flies the red, white, and black, with the cardinal as its mascot. Its most recent logo with York sliced apart was adopted in 2011. Prior to that it used a spread out Y on its literature and banners. This concludes our tour of CUNY York College.

When it comes to higher education, Forgotten-NY so far visited 20 local campuses. I’ve been to Hunter College, CCNY, Queensborough Community College, SUNY Maritime, St. John’s University, and Kingsborough Community College.

Kevin Walsh has been to Wagner, Bronx Community College, Columbia University, Lehman College, and Queens College. We both look forward to visiting and lecturing at other campuses across the city. Because no other city as many colleges and universities as New York.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press)

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

5/28/18

2 comments

Do you have some connection with the college that enables you to get access?

I showed my ID to the security guard and noted that I had an appointment at the library.