By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

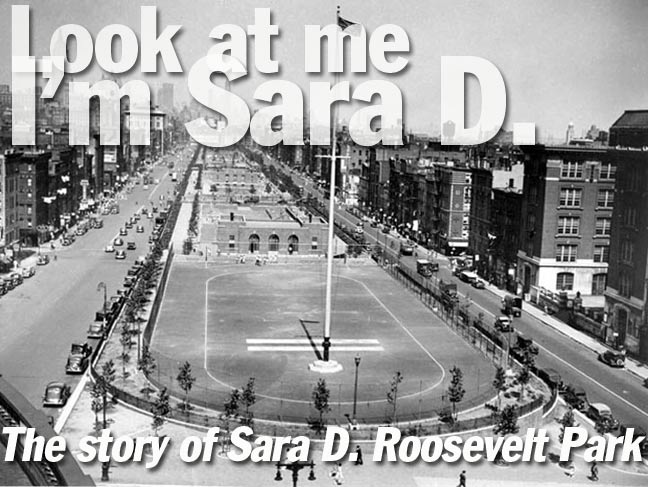

In the crowded Lower East Side of Manhattan there is a linear park covering seven blocks between Houston and Canal Streets. It is the product of Depression-period slum clearance that provided much-needed public green space for the poor, tired, huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

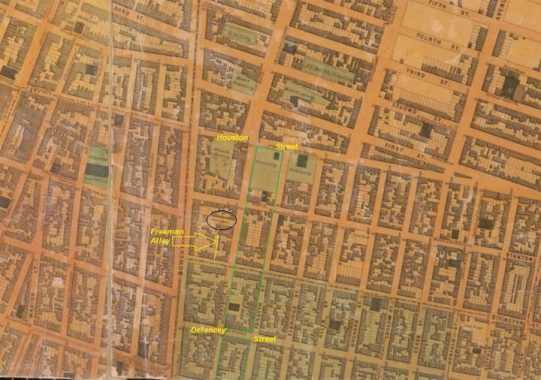

Before this park was built, its site contained cemeteries, synagogues, and a short-lived luxury hotel tower. Forsyth and Chrystie Street follow the park’s length, offering historic buildings that withstood the neighborhood’s demographic changes and urban renewal schemes. The 1852 Matthew Dripps map shows a cemetery, two Baptist churches, an Episcopal church, a Reform temple, and an armory on the park’s footprint. Circled is an African American cemetery which I will discuss below.

I arrived at Sara D. Roosevelt Park to inspect the conditions of its Golden Age Center, an unremarkable Modernist facility completed in 1964. Except for the artwork on its southern wall, the building has mosaics but no plaque indicating their artist or date of completion. Behind the building on its north side is where history is to be discussed.

The M’Finda Kalunga Garden was founded in 1982 in a neglected section of the park frequented by drug users and vagrants. The name of this reclaimed green space is translated to mean “Garden at the Edge of the Other Side of the World” in the Kikongo language that was spoken by many of the city’s first African-Americans when they arrived here as slaves. Across the street from this garden, the property at 195-197 Chrystie Street served as the city’s second African Burial Ground, after the first one in the Civic Center was closed and desecrated with development. This cemetery received burials from 1795 until 1853. Freeman Alley is on this block. It’s possible that the name may be related to the cemetery, but so far I haven’t found any evidence for it. Most of the remains were reinterred at Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, which hosts relocated graves from a few other small cemeteries that were decommissioned in favor of urban growth.

Urban waterways are my specialty. On this matter, a tiny pond for goldfish and turtles can be found in M’Finda Kalunga Garden. The period when the city’s second African American cemetery operated was one of transition as Africans became more American. Slave importation was abolished in 1808, and twenty years later the state’s last slaves were released from ownership. Within a decade of the cemetery’s closing, the Civil War would put an end to this dehumanizing practice. The cemetery was under the auspices of St. Philip’s Church, a church for “free Africans” founded in 1809. Like the story of the city’s largest Reform Temple, and its Catholic cathedral, this historic Black congregation kept moving uptown. It is presently located in Harlem. The park has a second garden designed by a more recent immigrant community, the Hua Mei Bird Garden, named after a popular songbird in China.

Also on Chrystie Street one can see the contrast between the 19th and 21st centuries. 163 Chrystie has a German Rundbogenstil, or “round arch style.” This was a mid-19th Century attempt in Germany to develop a national architectural style. Kevin’s tour of 14th Street from October 2019 offers more examples of Rundbogenstil. Next door, 165 Chrystie offers the post-millennial look of floor-to-ceiling glass windows and concrete walls. Designed by ODA Architecture, the 9-unit luxury residence replaced a three-story Chinese kitchen supply store.

At Stanton Street there is an art installation from 2016 by street artist KAWS a.k.a. Brian Donnelly. His work was part of a $300,000 commitment by Nike in redesigning the basketball court. Nearly four years later, the painting still looks good. Kevin walked Stanton Street in 2010.

On the east side of the park facing this basketball court is the former Public School 20, one of many historically-inspired schools designed by C.B.J. Snyder. In 1985 at the height of the AIDS crisis this former school became the Rivington House, a 219-bed nursing home for patients afflicted with this incurable virus. In 2015, the facility closed and was sold to a politically-connected nursing home operator who then sold it to a private developer who had dreams of a luxury condo conversion here. Investigations and controversy ensued. In 2019, a mystery LLC purchased the building, which is leased for 30 years to Mount Sinai Hospital as a clinic. If you choose to go east on Rivington Street, Kevin walked this street in 2010.

Returning to the Golden Age Center, we are standing on the site of the tallest building demolished to make way for Sara D. Roosevelt Park. The 12-story Libby’s Hotel & Baths set the luxury standard in this otherwise working-class neighborhood. It was completed in 1926 and named after the mother of its owner Max Bernstein. Billed as the Ritz with a Shvitz, the $3 million hotel symbolized the Roaring Twenties and its owner as an immigrant success story. Libby’s had its own Yiddish radio show broadcasted from the hotel. Bernstein did not have luck on his side. Besides losing his mother at a young age, his wife died shortly after the hotel’s opening, sending him into a depression. Then a predatory lender foreclosed on the property in 1929. Within two years it was demolished to make way for the park.

The hotel faced Delancey Street, a wide thoroughfare connecting Little Italy to the Williamsburg Bridge. Prior to the bridge, Grand Street served as the neighborhood’s main east-west route on account of its ferry terminal.

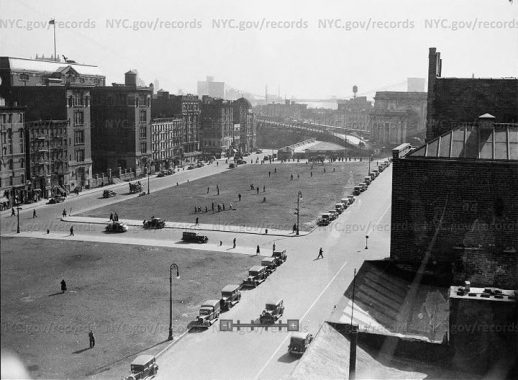

Following the completion of the bridge this street was widened to accommodate the increased traffic but I’ve wondered why Delancey wasn’t extended through SoHo to reach the west side. In the above 1934 photo from Municipal Archives, we see the site of Libby’s Hotel with Delancey Street in the foreground.

The widening allowed for a green median on Delancey that was initially to resemble a parkway. In 1921 it was given the name Schiff Parkway, a name that is as remembered as Avenue of the Americas and Joe DiMaggio Highway. Namesake Jacob Schiff was a German Jewish immigrant who achieved tremendous success in finance. This Upper East Side millionaire identified with the poor Jews of the Lower East Side not only through his philanthropy but also by walking its streets without being identified. His name also appears on an uptown playground. As the traffic flow increased, Schiff Parkway was narrowed in favor of more traffic lanes. The same story happened with Park Avenue’s malls and 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights.

In the past decade, Schiff Parkway’s width was partially restored thanks to the bike lane on Delancey Street that took away one traffic lane.

Speaking of namesakes, Sara D. Roosevelt was alive when the Board of Aldermen named this park for her in September 1934. The runner up-honoree was former Parks Commissioner Charles B. Stover. A humble woman, she preferred to have it named after social worker Lillian Wald, who had strong ties to the neighborhood. Her family has roots in New York reaching back to the Dutch period, and her oldest son was the president. Keeping out of the fray, she excused herself from the park’s dedication ceremony.

Not enough Roosevelts for you? Check out my earlier essay on Theodore Roosevelt Park and FDR’s missing memorial in Midwood. Kevin takes us back to the demapped Roosevelt Street that predates both presidents and their mothers.

Three blocks to the east of this intersection the Tenement Museum has a corner storefront promoting immigration history in this city. Once a modest tenement-turned-museum at 97 Orchard Street, it has since undergone an expansion that includes offices, storefront, and an elevator, among other accessibility improvements. Kevin walked the length of Orchard Street in 2018 and documented the fading ads of Delancey in 1999.

I’m Just Walkin’ blogger Matt Green calls the facility on Delancey and Forsyth a “churchagogue,” and he’s seen plenty of them across the city. The Spanish Delancey Seventh Day Adventist Church offers hints of its Jewish past with stars of David on its windows. Its designer, J. Cleveland Cady, also had the American Museum of Natural History and the old Metropolitan Opera House on his resume. Built in 1890 for a missionary church, it had no luck converting Jewish immigrants and soon became a palatial synagogue. The owners wisely rented out the first floor to storefronts.

In the 1960s, the synagogue had few members, as younger generations moved uptown, out of Manhattan, and towards the suburbs. The church purchased this shul in 1971. Under its current owner, services here still take place on Saturdays. In 2016, the church offered its site for development, with the provision to retain the first three floors. This building is not landmarked. So far, no glass box tower here yet. Check back here in a couple of years.

At 104 Forsyth Street facing the park with a presidential surname is the apartment building honoring the 20th president, who served for just six months in 1881 when he was assassinated. Like its namesake, the building has some sad stories of its own. Daytonian in Manhattan blogger Tom Miller gives us a detailed history of The Garfield Flats.

Here’s another former synagogue, 80 Forsyth Street. Again, Tom Miller gives us its history, so I don’t have to. Its most remarkable owners were artist couple Pat Pasloff and her husband Milton Resnick, who bought the building in 1966. Resnick also owned a former synagogue-turned-studio a block away on Orchard Street. In 2013 after Pasloff’s death, the studio was put on the market for $6.2 million.

On this block the park also wiped away The Grand Theatre, a palace of Yiddish plays that was part of a cluster of theaters nearby on the Bowery dubbed the Yiddish Rialto. This 1,700-seat theatre welcomed neighbors from nearby Little Italy and Chinatown with plays in their respective languages. Prolific city photographer Percy Loomis Sperr was on the scene to capture the demolition of this beautiful structure. In this NYPL Digital Collections photo, Sperr is looking south on Chrystie Street towards Grand Street. Libby’s Hotel and Grand Theatre were the last buildings demolished in favor of the park, on account of their size.

I’m surprised that Tom Miller hasn’t yet chronicled 70 Forsyth Street, built as The Major. This five-story walkup seems like an ideal counterpart to the Grand Theatre, similar to how the Farley Post Office complimented the old Penn Station across the street. The Major and the Grand Theater were built in the same generation, but I do not know if they shared an architect. The building is not mentioned in the AIA Guide and it is not landmarked. Similar to how Jewish immigrants of the early 20th century created landsmanshaften of newcomers from the same villages and regions, Chinese newcomers at the turn of this century are doing the same. 70 Forsyth Street is home to the New Fuzhou Senior Association, representing folks from the capital city of the Fujian Province.

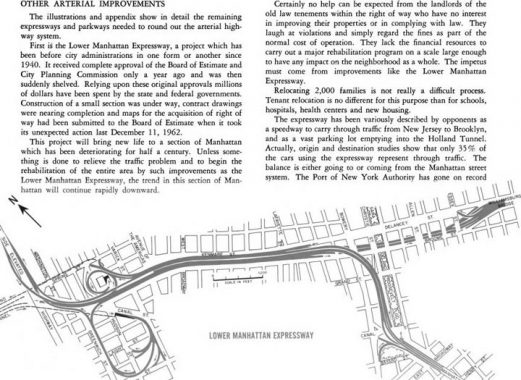

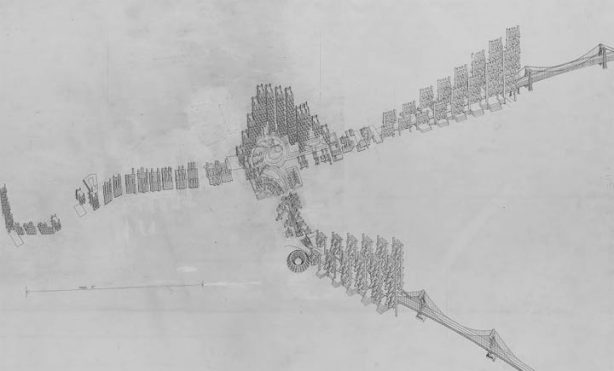

The beauty of Sara D. Roosevelt Park was almost compromised by the man who ran the city’s Parks Department. In his effort to steamroll a highway across lower Manhattan, Robert Moses saw this park as an easy path for the Lower Manhattan Expressway, or Lomex. In a 1955 illustration from the Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority, the highway is shown running atop the block to the west of the park, taking away dozens of tenements and small businesses so that cars can travel between Brooklyn and New Jersey without any traffic lights. And this was only a spur of Lomex. The main highway’s route was east-west between Delancey and Broome Streets, running from the Holland Tunnel to Williamsburg Bridge.

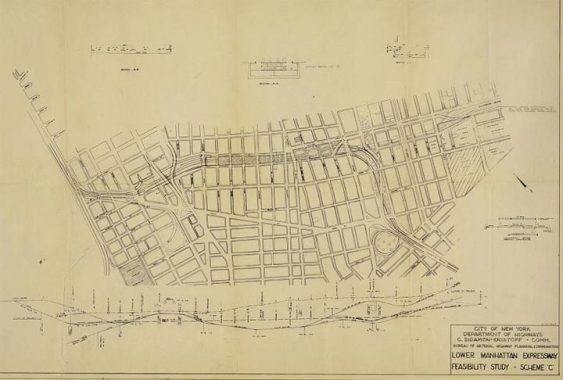

The 1963 Arterial Program by TBTA shows the full length of Lomex, its tentacle-like ramps, and how “relocating 2,000 families is not really a difficult process.” This plan would have encroached on the park at Broome Street, and would have razed the block where the Tenement Museum is located. Thousands of tenements have been demolished in favor of public housing, schools, roads, and parks. By sheer luck, 97 Orchard Street survived long enough to become a museum!

In the 1967 plan drafted by the city’s DOT, we see the highway taking over the park entirely south of Delancey Street. The parkland loss would have been made up with a new set of parks above a highway trench in SoHo. Delancey/Kenmare and Broome streets would have been relegated as service roads for the main Lomex route.

To account for the “relocation of 2,000 families,” architect Paul Rudolph proposed a linear “city within the city” atop the Lomex with brutalist stepped concrete high-rises covering the highway, which would have been built atop Sara D. Roosevelt Park. At its junction with Canal Street and Manhattan Bridge, Rudolph proposed a massive transit hub whose shape is somewhere between a nautilus spiral and a domed arena. The Confucius Plaza high-rise stands there today. Fortunately this expressway did not succeed and the park was saved.

The southernmost block of Sara D. Roosevelt Park, between Hester and Canal Streets, has seen dramatic change on its eastern side. In this 1934 photo from the Municipal Archives, we see the cleared park block looking south. The dome in the background is the synagogue at 27 Forsyth Street. Most synagogues on the LES were comprised of landsmen from specific places; this one was founded by Jews from Suwalki, Poland. The synagogue failed to pay its bills and was forced to close in 1926. The building is still Orthodox in name: since 1935 as St. Barbara’s Greek Orthodox Church, an outpost of Greek culture in this largely Chinese neighborhood.

In 1934 this block contained IS 131, another fine C.B.J. Snyder product. But as the student body grew and its needs changed, the old school was razed and replaced in 1983 with a modernist facility. In the above photo, we see this school on the right side of the park. The photographer took this shot standing atop the Manhattan Bridge entrance arch. The southern side of this park is Canal Street, where Kevin walked in 2019.

The circular edges of Intermediate School 131 have the look of a Guggenheim knockoff or garage ramps, spilling over a remapped block of Forsyth Street facing the park. The school is co-named for Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, leader of the Xinhai Revolution that overthrew China’s last imperial dynasty in 1911. The annual Lunar New Year Parade marches past this building with pride. My story on these seven historic blocks ends here.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

2/11/20

7 comments

Thank you for this! It’s a wonderful short history of the Sara D Roosevelt Park and the links. We look forward to browsing through them all. We are still here and going strong. Come back in the spring/summer to see the gardens (we have many) as the greenery is lush. We have Audubon NY

building an indigenous demonstration garden, The Hort working on Hester Street with Emma Lazarus HS, The Tenement Museum staffers have

taken on the (New) Forsyth Conservancy Garden, The Elizabeth Hubbard Garden (former chair and first African American Ballerina in Rockefeller Center’s ballet corps, a memorial garden to the homeless individuals who have perished in the neighborhood, a Rivington House memorial garden and the Hua Mei Bird Sanctuary (used most Saturday and Sunday mornings in warm weather).

Remarkable account. Thanks for the scholarship.

Thank you.

Besides the potential damage to Sara D. Roosevelt Park that the Lower Manhattan Expressway would have caused, major subway construction in the area between 1957 and 1967 temporarily disrupted Chrystie Street and adjacent portions of the park. That work was, of course, the Chrystie Street Connection, built to connect the IND Sixth Avenue subway with the BMT routes crossing the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges. A portion of the park, between Houston and Delancey Streets, was torn up to make the connection to the Williamsburg Bridge, and is used by today’s M train. The Chrystie Street Connection opened in two stages, November 1967 and July 1968, and the park was completely restored.

My own book, From a Nickel to a Token, devotes an entire chapter (#19) to the Chrystie Street project and includes construction photographs of the area. The long-term result of the Chrystie Street project was the integration of the IND and BMT into today’s B Division, or lettered lines.

Way back in the 1960’s-1970’s, my mother taught science at what was JHS 65 (Charles Sumner School) and she would walk to and from this now-demolished school along Forsyth Street. I had never visited this area of lower Christie Street except for shopping at Ezra Cohen’s, a linen store located on Grand Street (great bed linens!). It was quite an experience as the construction of the Chrystie Street Connection had everything torn up!

My memories of walking along Chrystie Street are now a bit fuzzy as Mom is now 92 (as of 2020) and our family had long moved away from NYC: my parents moved to upstate NY before I then moved to the metro Washington DC area to work in corporate America; my brother also moved upstate after college. I am still so happy that the Russ & Daughters shop is still open at its original location on Houston Street with Katz’s Delicatessen still nearby; it makes any visit to the Big Apple truly a treat!

Jacob Schiff donated $250,000 or $500,00 to Barnard College in 1915 (sources vary on which amount) for the central building on campus, now known as Barnard Hall, said to be the only building with the same name as the college it is in. The obstacle was that the appropriate name Schiff Hall seemed to some trustees as too Jewish. But take the money, right? There is at least a large brass dedication to Schiff in the lobby.

In the 1950s or 1960 I speed skated at sara d Roosevelt Park & won twice in 2 years in what paper was that printed in please